The European Space Agency (ESA) and Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA) have unveiled the probe they're sending to study Mercury in 2018, tasked with figuring out why the smallest planet in the Solar System appears to be shrinking.

The BepiColombo spacecraft is also going to be tasked with looking for water ice at Mercury's poles and in its volcanoes, which should give us more clues about the composition and evolution of the planet.

"Mercury is the least explored of the rocky planets, but not because it is uninteresting," says the head of the ESA, Alvaro Giménez Cañete. "It's because it's difficult – difficult to get there, even more difficult to work there."

Mercury lies some 77 million kilometres (or 48 million miles) away from Earth, but that's not as much of a problem for scientists as the planet's very thin atmosphere, which makes slowing down a probe hurtling through space very difficult.

To put the brakes on as much as possible before it gets to Mercury, BepiColombo will go through a total of nine fly-bys – one around Earth, two around Venus, and six around Mercury – to use up some of its energy.

Rendering of BepiColombo in flight. Credit: ESA/ATG medialab

Rendering of BepiColombo in flight. Credit: ESA/ATG medialab

By the time the probe settles down into orbit, sometime in 2025, it will have covered a distance equivalent to going around the Solar System 18.5 times.

Once in position, BepiColombo will need to survive through the extreme temperatures of Mercury, which can range from -170 degrees Celsius (-280 degrees Fahrenheit) during the night to 430 degrees Celsius (800 degrees Fahrenheit) during the day.

"It's like operating a spacecraft in a pizza oven," says BepiColombo project manager Ulrich Reininghaus of the ESA.

The spacecraft is actually going to split up into two probes when in orbit, one made by the ESA and one made by JAXA.

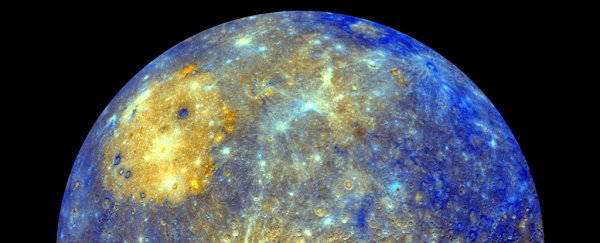

Then the real scientific work can begin, building on data collected by the two previous probes to visit the planet: Mariner 10, which arrived in 1974, and Messenger, which arrived in 2008 and has given us our best pictures of the planet.

BepiColombo ready to go. Credit: ESA–C. Carreau, CC BY-SA 3.0 IGO

BepiColombo ready to go. Credit: ESA–C. Carreau, CC BY-SA 3.0 IGO

Measurements of the surface suggest Mercury is tectonically active and shrinking still today as its core cools – and scientists want to know why.

They also want to look for evidence of water ice hidden away in the shadowy craters and volcanoes of Mercury, protected from the fierce solar glare and heat. If BepiColombo can take chemical measurements from the ice, it might give us a better idea of how Mercury was formed in the first place.

Mercury is also special because it sits so deep in the Sun's gravitational field. Scientists want to use BepiColombo to test Einstein's general theory of relativity with up to 100 times more accuracy than they can here on Earth.

Another mystery is why Mercury has a large iron core topped with a thin layer of silicate rocks. The hypotheses that the Sun eroded some of its outer layers, or that they were knocked off by a collision with another planet, don't match up with the surface scans that Messenger took.

By using more accurate instruments and taking a closer look at Mercury, the experts at ESA and JAXA are hoping to get answers to some of these questions, and we can't wait to see what it's going to find.

If you want to see the ESA briefing in full it's available below: