Scientists have long known that animals have some kind of internal compass that allows them to use Earth's magnetic field to navigate. This ability allows species such as the monarch butterfly to travel up to an incredible 5,000 km across the US to the exact same location, year after year, and the Arctic tern to travel 71,000 km between Greenland and Antarctica annually. But these magnetic fields are pretty much invisible to humans, and we've never been able to find the sensor that lets animals to detect them.

Now a team of researchers from the University of Texas at Austin in the US has identified a tiny antenna-like structure in the brain of worms that allows them to sense Earth's magnetic field, and they suspect the same structure could be the key to helping other species navigate, too.

"Chances are that the same molecules will be used by cuter animals like butterflies and birds," one of the researchers, Jon Pierce-Shimomura, said in a press release. "This gives us a first foothold in understanding magnetosensation in other animals."

Back in 2012, scientists found cells in pigeons that process information about magnetic fields, but this is the first time researchers have ever found the actual sensor in animals.

"It's been a competitive race to find the first magnetosensory neuron," said Pierce-Shimomura. "And we think we've won with worms, which is a big surprise because no one suspected that worms could sense the Earth's magnetic field."

The team made the discovery while conducting Alzheimer's research in small soil worms, C. elegans. They noticed that when worms from Texas soil were hungry, they moved downwards to look for food. But worms that came from other parts of the world - Hawaii England and Australia, for example - didn't move down; they moved at a precise angle to the magnetic field that would have corresponded to down if they'd been in their home country.

The team then altered the magnetic field around the worms' enclosure using a special magnetic coil system, and found that they changed their behaviour accordingly.

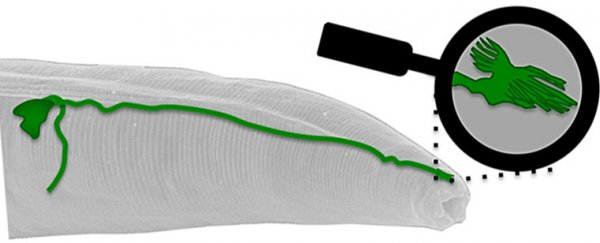

But the real breakthrough came when they worked with worms that had been genetically engineered to block a structure called the AFD neuron from forming in the brain. These worms didn't change their behaviour when the magnetic fields around their enclosure were altered – in fact, they seemed unable to detect the magnetic fields at all.

The AFD neuron is a tiny structure at the end of a neuron that gives worms the ability to sense carbon dioxide levels and temperature while underground. To confirm its additional role in sensing magnetic fields, the team used a technique called calcium imaging to show that changes in the magnetic field caused the AFD neuron to light up. Their findings have been published in the journal eLife.

The next step will be to confirm that this AFD neuron exists in other species and that it works in the same way. If that's the case, we might finally have an explanation for the incredible navigation abilities of animals, and perhaps a roadmap for how humans could one day achieve the same ability.