Scientists have discovered a brand-new type of cell hiding inside the delicate, branching passageways of human lungs.

The newfound cells play a vital role in keeping the respiratory system functioning properly and could even inspire new treatments to reverse the effects of certain smoking-related diseases, according to a new study.

The cells, known as respiratory airway secretory (RAS) cells, are found in tiny, branching passages known as bronchioles, which are tipped with alveoli, the teensy air sacs that exchange oxygen and carbon dioxide with the bloodstream.

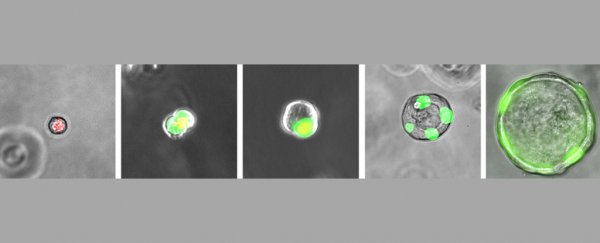

The new RAS cells are similar to stem cells – "blank canvas" cells that can differentiate into any other type of cell in the body – and are capable of repairing damaged alveoli cells and transforming into new ones.

Researchers discovered the RAS cells after becoming increasingly frustrated by the limitations of relying on the lungs of mice as models for the human respiratory system. However, because of certain differences between the two, scientists have struggled to fill some knowledge gaps about human lungs.

To get a better understanding of these differences on a cellular level, the team took lung tissue samples from healthy human donors and analyzed the genes within individual cells, which revealed the previously unknown RAS cells.

"It has been known for some time that the airways of the human lung are different than in the mouse," senior author Edward Morrisey, a professor at the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania who specializes in respiratory systems, told Live Science.

"But emerging technologies have only recently allowed us to sample and identify unique cell types."

Related: 10 strangest medical cases of 2021

The team also found RAS cells in ferrets, whose respiratory systems are more similar to humans' than those of mice are. As a result, the researchers suspect that most mammals equal or larger in size are likely to have RAS cells in their lungs, Morrisey said.

RAS cells serve two main functions in the lungs. First, they secrete molecules that maintain the fluid lining along bronchioles, helping to prevent the tiny airways from collapsing and maximizing the efficiency of the lungs.

Second, they can act as progenitor cells for alveolar type 2 (AT2) cells, a special type of alveoli that secrete a chemical that is used in part to repair other damaged alveoli. (A progenitor cell is a cell that has the capacity to differentiate into another type of cell, similar to how stem cells differentiate into other cells.)

"RAS cells are what we've termed facultative progenitors," Morrisey said, "which means they act as both progenitor cells and also have important functional roles in maintaining airway health." This means RAS cells play a vital role in maintaining healthy lungs, he added.

The researchers think RAS cells may play a key role in smoking-related diseases, such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). COPD is the result of inflammation of airway passages inside the lungs, which can be caused by smoking and, occasionally, air pollution, according to the Mayo Clinic.

The inflammation of the airways makes it harder for the lungs to properly take in enough oxygen; as a result, COPD has similar symptoms to asthma. COPD can also lead to emphysema, in which alveoli are permanently destroyed, and chronic bronchitis, a long-lasting and intense cough usually accompanied by excess phlegm.

Every year, more than 3 million people around the world die from COPD, according to the World Health Organization.

In theory, RAS cells should prevent, or at least alleviate, the effects of COPD by repairing damaged alveoli. However, the researchers suspect that smoking can damage, or even completely destroy, the new cells, leading to the onset of diseases such as COPD.

Patients who have COPD are often prescribed anti-inflammatory drugs or oxygen therapy to ease their symptoms. However, these are only temporary solutions and do nothing to reverse lung damage.

RAS cells could potentially be used to improve treatments or even cure COPD, if researchers can properly harness these cells' regenerative properties.

"We really don't know if this discovery could lead to a potential cure for COPD yet," Morrisey said.

"However, since COPD is a disease we know very little about, any new insight should help the field start to think about new therapeutic approaches that could lead to better treatments."

The study was published online March 30 in the journal Nature.

Related Stories:

The 10 deadliest cancers, and why there's no cure

10 of the strangest medical studies (in recent history, that is)

This article was originally published by Live Science. Read the original article here.