A popular prescription drug that is used to treat type 2 diabetes or to manage weight in adults seems to be both safe and effective for weight loss in children – at least in the short term, according to new results.

Liraglutide (brand name Victoza or Saxenda) belongs to the same class of medicine as semaglutide, which is the drug behind Ozempic and Wegovy.

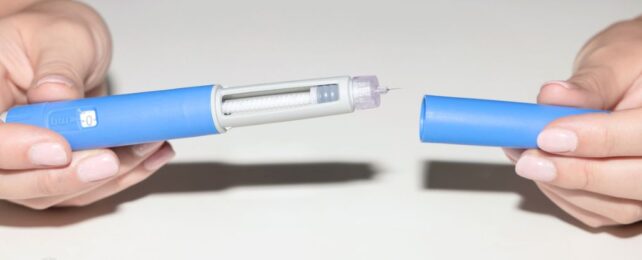

The subcutaneous injection was first approved in the US as an adjunct therapy for type 2 diabetes in 2010. Four years later, it was approved for weight management in adults who are considered overweight or obese.

Despite its surging popularity, the long-term effects of liraglutide and similar drugs are still being investigated, even among adults. Their use among children remains controversial.

While some scientists have warned that liraglutide may be dangerous or have unintended consequences for kids in the long run, in 2019, the US Food and Drug Administration approved liraglutide for use in patients with type 2 diabetes who are 10 years or older.

To date, no medications are currently approved for the treatment of obesity in children younger than 12.

A phase 3 clinical trial among 82 participants has now provided initial results that liraglutide, combined with other lifestyle interventions, is both safe and effective as a weight loss drug for children as young as six years old.

Roughly a year after starting the trial, which was funded by liraglutide maker Novo Nordisk, participants between the ages of 6 and 12 who were given the liraglutide reduced their body mass index by 5.8 percent. Those given a placebo over the same period showed increased BMIs by about 1.6 percent.

Children at this age are still growing, so it is expected that some weight gain would occur without drug treatment over the course of a year.

All participating children were counseled by qualified health care professionals and encouraged to eat healthily and exercise for an hour or so a day.

"In our study, diastolic blood pressure and… a measure of blood sugar control improved more in children receiving liraglutide than in those receiving the placebo," explains lead researcher and pediatrician Claudia Fox from the University of Minnesota Twin Cities. Fox has received grant and contact support from Novo Nordisk and another pharmaceutical company, Eli Lilly.

The prevalence of negative side effects was about the same among both groups, although transient gastrointestinal issues, like nausea and vomiting, were nearly 30 percent more common in the liraglutide group.

"To date, children have had virtually no options for treating obesity," argues Fox.

"They have been told to 'try harder' with diet and exercise. Now with the possibility of a medication that addresses the underlying physiology of obesity, there is hope that children living with obesity can live healthier, more productive lives."

In an accompanying editorial, pediatricians Julian Hamilton-Shield and Timothy Barrett argue that Fox and her colleagues have provided "much-needed evidence" for the effects of liraglutide on young children with obesity.

But body composition was not measured in the trial, and BMI is a poor surrogate for fat mass, they note.

After treatment was ceased, children in the liraglutide group of the trial showed increased BMI scores, "which is worrisome because it implies the ongoing need for pharmacotherapy to prevent BMI rebound," explain Hamilton-Shield and Barrett.

The same concerns also apply to adults taking these medications. Once the injections are stopped, studies have found the average patient typically regains about two-thirds of their lost weight within a year.

Significant fluctuations in weight during childhood could be a serious risk for ongoing development.

In a commentary published last year, some scientists (with no conflicts of interest to declare) warned that "little attention has been paid to the possible unintended consequences or adverse impact of these medications on children and adolescents during their critical period of growth and development."

Given that the long-term side effects of incretin mimetics are still being realized in adults, there's every reason to tread cautiously.

The study was published in the New England Journal of Medicine.