We've got a curious case of mistaken identity to report. Fossils previously believed to have been left by prehistoric tentacle-bearing aquatic invertebrates called Bryozoans may in fact have been created by a different source: seaweed.

That's the conclusion of a new study of the 500 million-year-old remains, which took a fresh look at Protomelission gateshousei fossils that were thought to represent the oldest remnants of Bryozoans on record.

As well as apparently setting the record straight, the findings again change what we know about the evolution of Bryozoans. To date they're the only fossilized animals not to be around during the Cambrian explosion, when life on Earth really started accelerating.

"We tend to think of the Cambrian explosion as a unique period in evolutionary history, in which all the blueprints of animal life were mapped out," says paleontologist Martin Smith, from Durham University in the UK. "Most subsequent evolution boils down to smaller-scale tinkering on these original body plans."

"But if Bryozoans truly evolved after the Cambrian period, it shows that evolution kept its creative touch after this critical period of innovation – maybe the trajectory of life was not set in stone half a billion years ago."

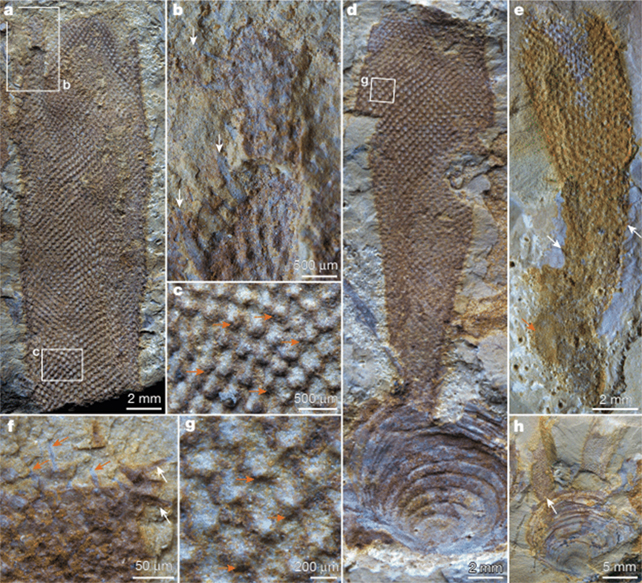

The study authors examined tiny P. gateshousei fossils found in the hills of southern China, separate from the batch that had been recognized as Bryozoans, and discovered previously unseen evidence of soft parts in their samples.

Those new revelations make these fossils a closer fit for green algae, in a group known as Dasycladales, the new study suggests – particularly in the signs of an external membrane that weren't present in the other fossil samples.

That in turn can teach us more about the Cambrian explosion: that these algae quite possibly played a more significant role than previously thought in the rapidly increased biodiversity that happened around that time.

"Where previous fossils only preserved the skeletal framework of these early organisms, our new material revealed what was living inside these chambers," says paleontologist Zhang Xiguang, from Yunnan University in China.

"Instead of the tentacles we would expect to see in Bryozoans, we discovered simple leaf-like flanges – and realised we were not looking at fossil animals, but seaweeds."

It means the earliest Bryozoan fossils that experts are more sure about don't appear until the geological period after the Cambrian, the Ordovician – that's some 40 million years after the point these fossils have been dated to.

The mysterious case of the missing Bryozoan fossils has apparently once again been opened. Why is this class of creature the only one not to feature in one of the most sudden bursts of life in the history of organisms?

One answer might be that we just haven't found the right clues yet. It's possible that the earliest forms of Bryozoans had softer parts, which means they wouldn't have left behind fossils in the first stages of their evolution.

"A growing number of Cambrian fossils… display characteristics that might be reconciled with a bryozoan affinity – but on the basis of presently available material, no taxon can be interpreted with sufficient certainty to document a pre-Ordovician origin of Bryozoa," write the researchers in their published paper.

The research has been published in Nature.