Usually when a star goes supernova, that's it. It's dead, kaput, RIP. But a new discovery could change how we view star deaths.

Astronomers have found a star that went supernova, managed to pull through, and then, 60 years later, went supernova all over again. That's just not how they're supposed to work.

Called iPTF14hls, the supernova was discovered in 2014, and at first looked just like any other supernova in the sky and was classified Type II-P.

In supernovae of this type, the core of a massive star collapses into a neutron star, sending a shockwave through the outer hydrogen-rich envelope, which it ejects into space. The ejected matter is ionised by the shockwave; later, it cools and recombines.

Supernova iPTF14hls's spectroscopic features were identical to those of a Type II-P supernova. But then several months later it did something supernovas don't usually do - it brightened again.

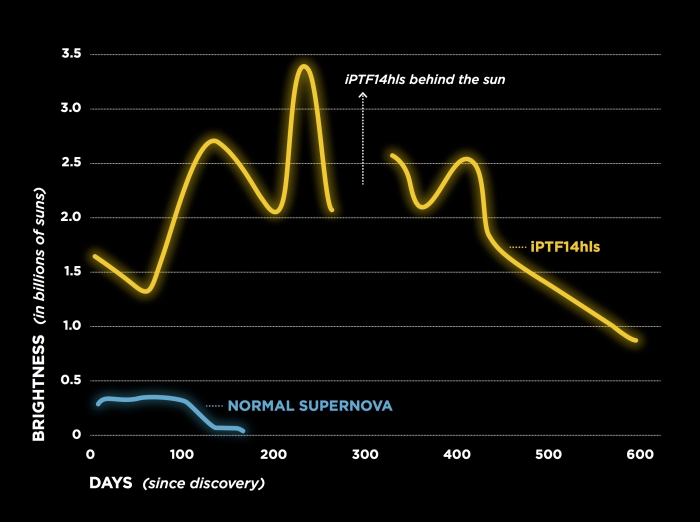

Over 600 days of observation, it dimmed and brightened several times - at least five occasions over less than three years. Usually, supernovas rise to peak brightness, shine for a few months, and then steadily dim.

(Adapted from Arcavi et al. 2017, Nature. Credit: LCO/S. Wilkinson)

(Adapted from Arcavi et al. 2017, Nature. Credit: LCO/S. Wilkinson)

When scientists from Las Cumbres Observatory went back and examined archival data, they found something amazing - an explosion in the exact same location in 1954.

"This supernova breaks everything we thought we knew about how they work," said lead researcher Iair Arcavi of the University of California Santa Barbara and Las Cumbres Observatory.

"It's the biggest puzzle I've encountered in almost a decade of studying stellar explosions."

In a paper published in the journal Nature, the researchers calculated that iPTF14hls's original star was large - at least 50 times more massive than the Sun, and probably much larger than that.

In fact, "supernova iPTF14hls may be the most massive stellar explosion ever seen," said researcher Lars Bildsten, director of UCSB's Kavli Institute for Theoretical Physics.

The researchers believe a potential explanation for iPTF14hls is that it's a pulsational pair-instability supernova - which would make it the first such event ever observed.

This is an event that seems to be a supernova but doesn't destroy its host star, and it generally occurs in stars around 95 to 130 solar masses.

During these eruptions, the star blows off its outer layer, shedding between 10 and 25 solar masses, bringing its weight down below 100. These events can repeat until eventually the star collapses into a black hole.

It's been hypothesised, but not confirmed, that the 1843 eruption of Eta Carinae A was a pulsational pair-instability supernova.

"These explosions were only expected to be seen in the early universe and should be extinct today," said researcher Andy Howell, a UCSB adjunct faculty member who leads the supernova group at LCO.

"This is like finding a dinosaur still alive today. If you found one, you would question whether it truly was a dinosaur."

But there's a problem with that hypothesis. The pulsational pair-instability model does not account for the continued presence of hydrogen.

After the 1954 explosion, supernova iPTF14hls retained a few tens of solar masses of hydrogen in its envelope. Additionally, the star's most recent explosion used more energy than can be accounted for by pulsational pair-instability.

Which means either that supernova iPTF14hls is a really, really weird pulsational pair instability supernova - or something completely new. The team is continuing the monitor the supernova in the hopes that the answer will be revealed over time.

"This is one of those head-scratcher type of events," said researcher Peter Nugent of the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory.

"At first we thought it was completely normal and boring. Then it just kept staying bright, and not changing, for month after month.

"Piecing it all together, from our observations at Palomar Transient Factory, Keck Observatory, LCOGT, and even the images from 1954 in the Palomar Sky Survey, has started to shed light on what this could be.

"I would really like to find another one like this."

The research has been published in Nature.