The melting of West Antarctica's ice shelves is likely to substantially accelerate in coming decades even if the world meets ambitions to limit global warming, according to research published Monday, warning it would drive rising sea levels.

Researchers warned that humans had "lost control" of the fate of thinning ice shelves – frozen ridges floating on the fringes of the main ice sheet that play a stabilising role by holding back the flow of glaciers into the ocean.

This region has already seen accelerating ice loss in recent decades and scientists have said that West Antarctica's vast ice sheet, which holds enough water to lift ocean levels by several metres, could be nearing a climate "tipping point".

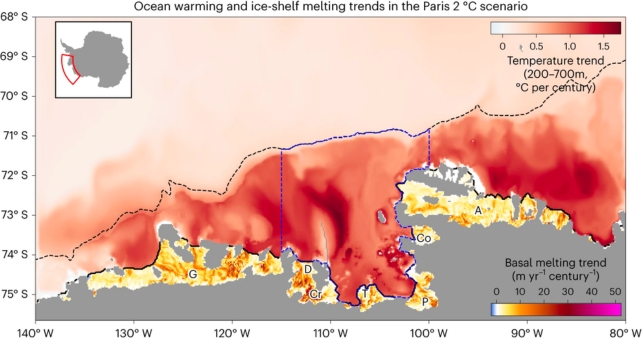

In the new study, researchers using computer modelling found that faster ice shelf melting is already inevitable in the coming decades as the ocean warms.

Their results were largely the same even in a scenario where greenhouse gas emissions are slashed and warming stays within the more ambitious Paris Agreement target of 1.5 degrees Celsius since pre-industrial times.

"It appears that we may have lost control of the West Antarctic ice shelf melting over the 21st century," said lead author Kaitlin Naughten, of the British Antarctic Survey.

The research, published in the journal Nature Climate Change, looked at the process of ocean waters melting the underside of the floating ice shelves in the Amundsen Sea.

Even in the best-case scenario, ocean warming was found to be around three times as fast in the 21st century as the 20th century.

"Our simulation suggests that we are now committed to a rapid increase in the rate of ocean warming and ice shelf melting for the rest of the century," Naughten told reporters.

'Wake-up call'

Although researchers did not simulate the exact implications for sea level rise, Naughten said they have "every reason to expect" that the finding would add to the phenomenon, already projected to be up to a metre by the end of the century.

"West Antarctic ice shelf melting is one impact of climate change that we are probably just going to have to adapt to," she said.

Many millions of people across the planet currently live in low-lying coastal areas and she said some "coastal communities will either have to build around or be abandoned".

Alberto Naveira Garabato, professor in physical oceanography at the University of Southampton, said the research was "sobering".

"It illustrates how our past choices have likely committed us to substantial melting of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet and its consequent sea level rise – to which we will inevitably have to adapt as a society over coming decades and centuries," he told Science Media Centre.

But he stressed that it should also be "a wake-up call" to avoid other severe climate impacts – including the melting of the East Antarctic ice sheet, which is currently deemed more stable.

"We can still save the rest of the Antarctic Ice Sheet, containing about 10 times as many metres of sea level rise, if we learn from our past inaction and start reducing greenhouse gas emissions now."

The study authors stressed that while ambitious emissions cutting would not make much difference to West Antarctica ice shelf loss in this century, they could have a bigger long-term impact.

The ice sheet is likely to take centuries or even millennia to fully respond to climate change.

Jonathan Bamber, a professor at the University of Bristol's School of Geographical Sciences, cautioned that the study is somewhat limited because researchers used just one ocean model and did not explicitly investigate the effect of warming waters on sea levels.

"This part of West Antarctica contains sufficient ice to raise global sea level by more than a metre so it's important to understand how it will evolve in the future," said Bamber, who was not involved in the research.