Great rivers of whale pee make a remarkable contribution to Earth's cycling of nutrients, a new study reveals.

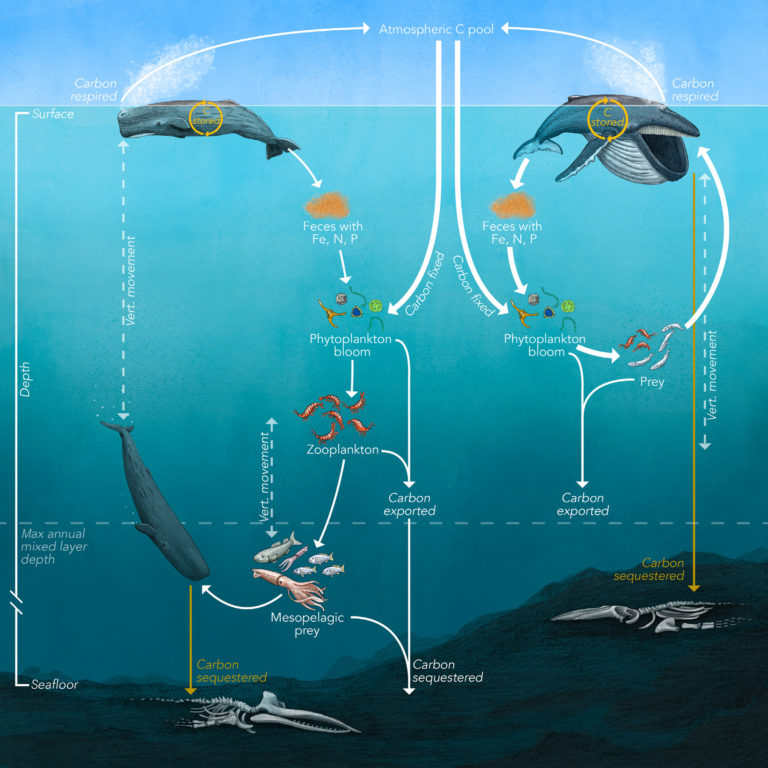

While their giant poop tsunamis pump nutrients vertically, from the surface to the ocean's depth, researchers have just calculated the astounding scales of their horizontal nutrient transport as well.

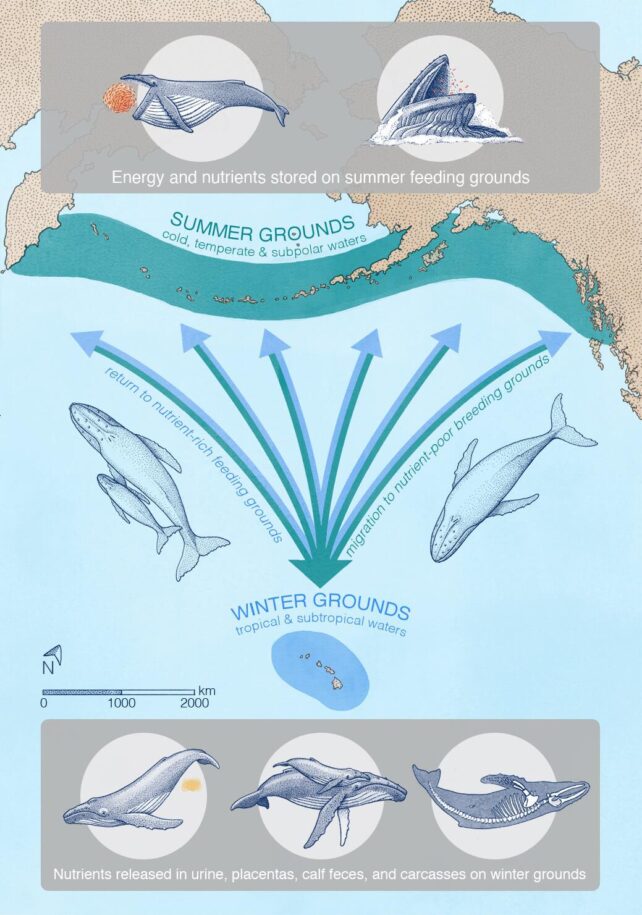

Baleen whales undertake some of the longest yearly migrations, with humpbacks (Megaptera novaeangliae) travelling up to 8,300 km (about 5,150 miles) from Antarctica to warmer wintering grounds. With them, the whales shuttle resources from nutrient-rich polar regions to the less resourced warmer regions of the oceans.

Amazingly enough, a huge amount of this nutrient distribution comes from whale urine, which disperses nitrogen and other elements through the ocean when nature inevitably calls.

"We call it the 'great whale conveyor belt'," explains the study's first author, conservation biologist Joe Roman from the University of Vermont in the US. "It can also be thought of as a funnel because whales feed over large areas, but they need to be in a relatively confined space to find a mate, breed, and give birth."

Scientists suspect mother whales stay near shallow, sandy waters because this environment helps muffle their constant communications with their babies.

"Moms and newborns are calling all the time," says Roman. "They don't want predators, like killer whales, or breeding humpback males, to pick up on that."

This means nutrients collected by the giant mamas slurping up clouds of krill and small fish during their wide-ranging feeding forays in summer are concentrated into a smaller area once they've migrated to give birth during winter.

For example, humpback whales that feed across the Gulf of Alaska spend their winters along the much smaller areas of Hawaii's shores, and between their waste, sloughed skin, and carcasses, they transport about double the nutrients provided by natural local forces.

"Nutrients are coming in from outside – and not from a river, but by these migrating animals," explains oceanographer Andrew Pershing, from Aarhus University in Denmark. "It's super cool and changes how we think about ecosystems in the ocean. We don't think of animals other than humans having an impact on a planetary scale, but the whales really do."

Roman and team calculated that between them, just a few migrating baleen whale species – gray (Eschrichtius robustus), humpback, and the three species of right whales (Eubalaena spp.) – shift about 3,800 tons of nitrogen and 46,000 tons of biomass yearly.

These whales are fertilizing Earth's productive coastal ecosystems, including our incredible coral reefs.

"Because of their size, whales are able to do things that no other animal does. They're living life on a different scale," says Pershing.

These figures don't even include the other migratory fin whales, like the largest living mammal, the blue whale (Balaenoptera musculus). We don't have enough data on many of their migratory patterns yet.

But it is clear that between the whale pump and conveyer belt, these majestic mammals play a massive role in shaping our ocean's gardens.

"The amount of nutrients transported would likely have been at least three times higher before commercial whaling," the researchers write in their paper.

Conservation efforts since the 1970s have seen some populations recover, like eastern Australia's humpbacks. Yet most of the world's whale populations remain depleted, as these gentle giants continue to face many threats from human activities. Those include ship strikes, fishery net entanglements, noise pollution, plastic pollution, climate change, and continued whaling.

Tactics like creating marine protection areas, with noise reduction and vessel speed limits where whales congregate have had promising results. If we can help boost whale numbers they can continue to keep our ocean ecosystems flourishing as well as help us clean up the spectacular mess we've made with climate change.

"Animals play an important role in moving nutrients," concludes Roman. "Seabirds transport nitrogen and phosphorus from the ocean to the land in their poop, increasing the density of plants on islands. Animals form the circulatory system of the planet – and whales are the extreme example."

This research was published in Nature Communications.