Sixty-six million years ago, an asteroid hit the Earth with the force of 10 billion atomic bombs and changed the course of evolution.

The skies darkened and plants stopped photosynthesizing. The plants died, then the animals that fed on them. The food chain collapsed. Over 90 percent of all species vanished. When the dust settled, all dinosaurs except a handful of birds had gone extinct.

But this catastrophic event made human evolution possible. The surviving mammals flourished, including little proto-primates that would evolve into us.

Imagine the asteroid had missed, and dinosaurs survived. Picture highly evolved raptors planting their flag on the Moon. Dinosaur scientists, discovering relativity, or discussing a hypothetical world in which, incredibly, mammals took over the Earth.

This might sound like bad science fiction, but it gets at some deep, philosophical questions about evolution. Is humanity just here by chance, or is the evolution of intelligent tool-users inevitable?

Brains, tools, language and big social groups make us the planet's dominant species. There are 8 billion Homo sapiens on seven continents. By weight, there are more humans than all wild animals.

We've modified half of Earth's land to feed ourselves. You could argue creatures like humans were bound to evolve.

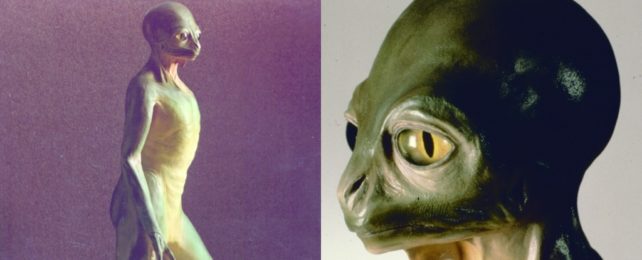

In the 1980s, palaeontologist Dale Russell proposed a thought experiment in which a carnivorous dinosaur evolved into an intelligent tool user. This "dinosauroid" was big-brained with opposable thumbs and walked upright.

It's not impossible but it's unlikely. The biology of an animal constrains the direction of its evolution. Your starting point limits your endpoints.

If you drop out of college, you probably won't be a brain surgeon, lawyer, or NASA rocket scientist. But you might be an artist, actor, or entrepreneur. The paths we take in life open some doors and close others. That's also true in evolution.

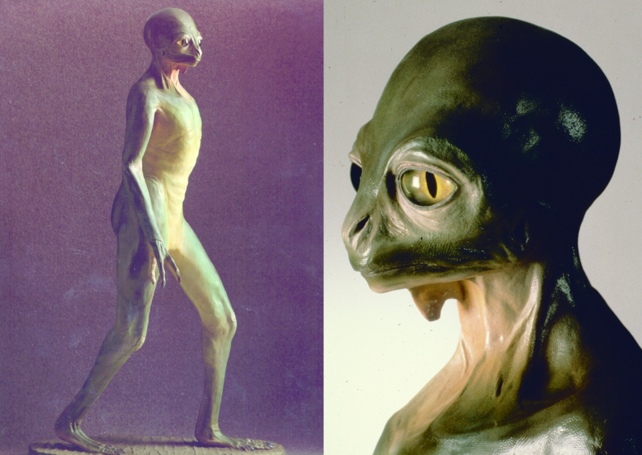

Consider the size of dinosaurs. Beginning in the Jurassic, sauropod dinosaurs, Brontosaurus and kin evolved into 30-50 tonne giants up to 30 meters long – ten times the weight of an elephant and as long as a blue whale.

This happened in multiple groups, including Diplodocidae, Brachiosauridae, Turiasauridae, Mamenchisauridae and Titanosauria.

This happened on different continents, at different times, and in different climates, from deserts to rainforests. But other dinosaurs living in these environments didn't become supergiants.

The common thread linking these animals was that they were sauropods. Something about sauropod anatomy – lungs, hollow bones with a high strength-to-weight ratio, metabolism, or all these things – unlocked their evolutionary potential. It let them grow big in a way that no land animals had ever before, or have since.

Likewise, the carnivorous dinosaurs repeatedly evolved huge, ten-meter, multi-tonne predators. Over 100 million years, megalosaurids, allosaurids, carcharodontosaurids, neovenatorids, and finally tyrannosaurs evolved giant apex predators.

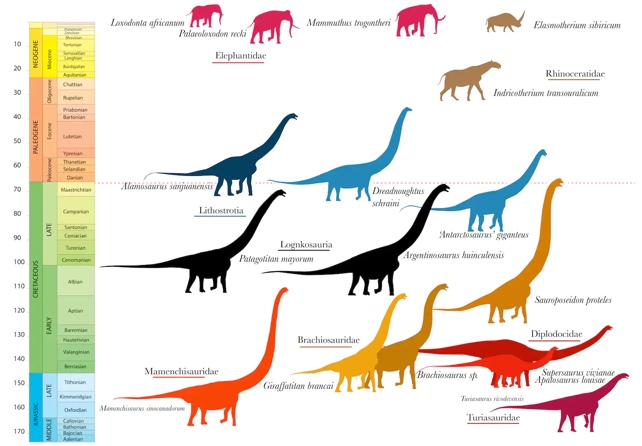

Dinosaurs did big bodies well. Big brains not so much. Dinosaurs did show a weak trend towards increased brain size over time. Jurassic dinosaurs like Allosaurus, Stegosaurus, and Brachiosaurus had small brains.

By the late Cretaceous, 80 million years later, tyrannosaurs and duckbills had evolved larger brains. But despite its size, the T. rex brain still weighed just 400 grams. A Velociraptor brain weighed 15 grams. The average human brain weighs 1.3 kilograms.

Dinosaurs did enter new niches over time. Small herbivores became more common and birds diversified. Long-legged forms evolved later on, suggesting an arms race between fleet-footed predators and their prey.

Dinosaurs seem to have had increasingly complex social lives. They started living in herds and evolved elaborate horns for fighting and display. Yet dinosaurs mostly seem to repeat themselves, evolving giant herbivores and carnivores with small brains.

There's little about 100 million years of dinosaur history to hint they'd have done anything radically different if the asteroid hadn't intervened. We'd likely still have those supergiant, long-necked herbivores, and huge tyrannosaur-like predators.

They may have evolved slightly bigger brains, but there's little evidence they'd have evolved into geniuses. Neither is it likely that mammals would have displaced them. Dinosaurs monopolised their environments to very end, when the asteroid hit.

Mammals, meanwhile, had different constraints. They never evolved supergiant herbivores and carnivores. But they repeatedly evolved big brains. Massive brains (as large or larger than ours) evolved in orcas, sperm whales, baleen whales, elephants, leopard seals, and apes.

Today, a few dinosaur descendants – birds like crows and parrots – have complex brains. They can use tools, talk and count. But it's mammals like apes, elephants, and dolphins that evolved the biggest brains and most complex behaviors.

So did eliminating the dinosaurs guarantee mammals would evolve intelligence?

Well, maybe not.

Starting points may limit endpoints, but they don't guarantee them either. Steve Jobs, Bill Gates, and Mark Zuckerberg all dropped out of college. But if dropping out automatically made you a multibillionaire, every college dropout would be rich. Even starting in the right place, you need opportunities and luck.

The evolutionary history of primates suggests our evolution was anything but inevitable. In Africa, primates did evolve into big-brained apes and, over 7 million years, produced modern humans. But elsewhere primate evolution took very different paths.

When monkeys reached South America 35 million years ago they just evolved into more monkey species. And primates reached North America at least three separate times, 55 million years ago, 50 million years ago, and 20 million years ago.

Yet they didn't evolve into a species who make nuclear weapons and smartphones. Instead, for reasons we don't understand, they went extinct.

In Africa, and Africa alone, primate evolution took a unique direction. Something about Africa's fauna, flora or geography drove the evolution of apes: terrestrial, big-bodied, big-brained, tool-using primates.

Even with the dinosaurs gone, our evolution needed the right combination of opportunity and luck.![]()

Nicholas R. Longrich, Senior Lecturer in Paleontology and Evolutionary Biology, University of Bath

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.