Humans are walkers, and we're really good at it.

Other creatures can walk on two legs - chimpanzees, for example, walk with bent knees and bent hips, kind of like Groucho Marx - but no animal walks the way we do, with the torso vertical, the legs extended, the stride long.

Paleoanthropologists point out that the ability to walk, and to do so with a minimum of expended energy, predated the evolution of big brains among human ancestors.

Walking freed the hands for tools and weapons, and allowed those species to roam far and wide to obtain food and other resources.

"Walking is huge. Walking set the stage for all of those things that come later," notes Carol Ward, a professor of anatomy at the University of Missouri.

But when did our ancestors begin to walk the way we do?

Footprints can provide a clue. Two sites in Laetoli, Tanzania, feature footprints of human ancestors who lived about 3.6 million years ago.

They were members of the genus Australopithecus. That's the genus of "Lucy," the 3.2 million-year-old human ancestor whose fossilized bones were discovered in Ethiopia in 1974.

Australopithecus afarensis skeleton Lucy, 3.2 million years old. (Michael Stravato/AP)

Australopithecus afarensis skeleton Lucy, 3.2 million years old. (Michael Stravato/AP)

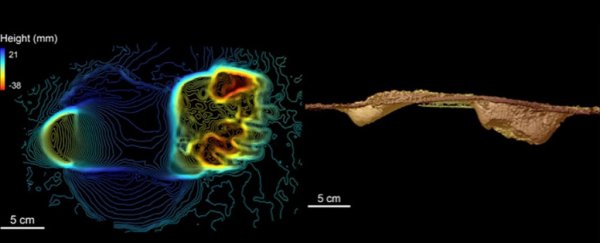

David Raichlen, an evolutionary anthropologist at the University of Arizona, has studied the Laetoli footprints and compared them to footprints made by human volunteers in laboratory settings.

He examined footprints of individuals walking normally and also those walking with bent knees and bent hips. (Scientists who study locomotion use the acronym BKBH).

The Laetoli footprints more closely match modern human footprints.

(David Raichlen/University of Arizona)

(David Raichlen/University of Arizona)

"Upright, humanlike bipedal walking goes back 4 to 5 million years," Raichlen told The Washington Post in advance of a symposium on the evolution of human locomotion, which took place Sunday at the Experimental Biology 2018 conference in San Diego.

"If you were in a time machine, looking at 'Lucy' in the distance, the way they walked would have looked very humanlike," said Ward, another symposium participant.

The ability to walk this way emerged through natural selection as our ancestors adapted to changing environmental conditions. The forests were drying out as a result of climate change.

Our primate cousins generally continued to live in trees, existing largely on ripe fruit, with their anatomy adapted for vertical climbing and swinging from branch to branch. But long ago, some chose a different path, striking out for the frontier.

They went to the ground more often and then, eventually, through many evolutionary changes they left the trees behind altogether.

Gone was the grasping big toe; instead, the big toe aligned with the other toes. And our arched feet are also an evolutionary development, because they stiffen rather than fold as we push off the back foot in our walking gait.

Other anatomical features keep our weight centered over our legs and our head steady as we walk.

Ian Wallace, an evolutionary biologist at Harvard University and another symposium presenter, said that "upright walking is the defining characteristic of the human lineage. Its consequences are hard to oversell."

There's a splendid description of human bipedality at the start of Wanderlust: A History of Walking by Rebecca Solnit, which was first published nearly two decades ago:

"Muscles tense. One leg a pillar, holding the body upright between the earth and sky. The other a pendulum, swinging from behind. Heel touches down. The whole weight of the body rolls forward onto the ball of the foot. The big toe pushes off, and the delicately balanced weight of the body shifts again. The legs reverse position."

2018 © The Washington Post

This article was originally published by The Washington Post.