More than 90 percent of us – including vets – think that different dog breeds have different levels of sensitivity to pain, even though there's little scientific evidence for it. Or at least there wasn't, until now.

In a study involving 10 different dog breeds, researchers from North Caroline State University confirmed canines do have a varying tolerance for, and sensitivity to, pain. Interestingly though, the findings didn't always match up with how vets view pain sensitivity across breeds.

"Veterinarians have a fairly strong consensus in their ratings of pain sensitivity in dogs of different breeds, and those ratings are often at odds with ratings from members of the public," says North Carolina State University veterinary behaviorist Margaret Gruen.

"So we wanted to know – first – is any of it true? If we take 15 dogs of 10 breeds rated as high, medium, and low sensitivity and test their sensitivity thresholds, would we see differences, and if so, would they be consistent with what veterinarians believe? Or is it possible that these views are the result of a dog's emotional reactivity and behavior while interacting with a veterinarian?"

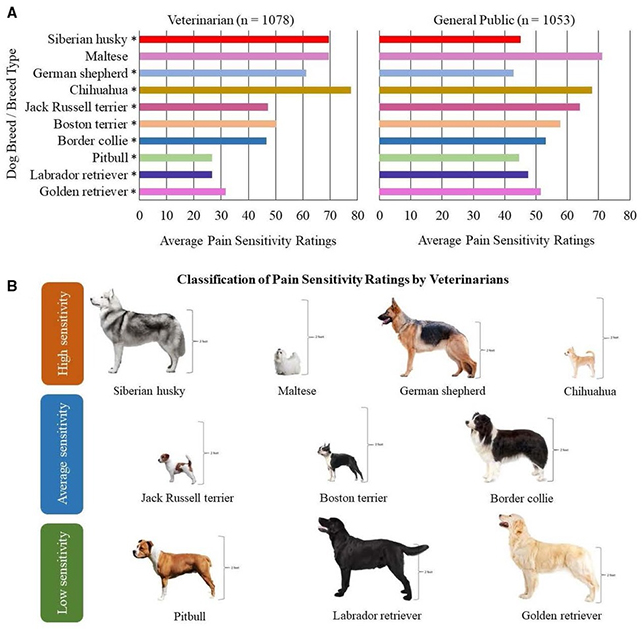

The study involved 149 male and female adult dogs in total, grouped by how vets and the general public rated them in terms of pain sensitivity: high (chihuahua, German shepherd, Maltese, Siberian husky); average (border collie, Boston terrier, Jack Russell terrier); or low (golden retriever, pitbull, Labrador retriever). Those with high pain sensitivity are thought of as having a lower pain tolerance.

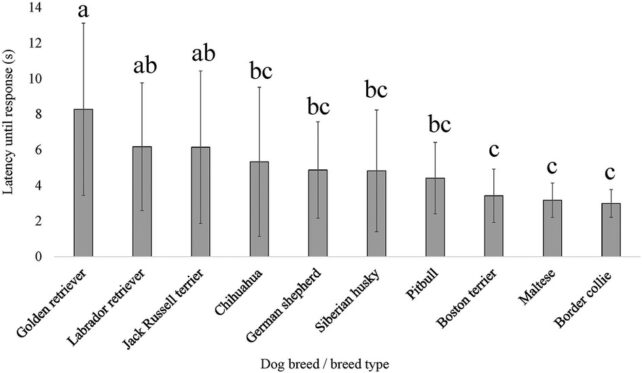

Adapting gentle external stimuli tests used on humans, the team tested dog pain sensitivity by pressing different objects against the paws of the canines.

Emotional reactivity was also measured, using a stuffed monkey that moved and made noises, and an interaction with a person the dog didn't know.

The results differed slightly between tests, but there was a distinct difference in pain sensitivity across breeds, which is in line with public opinion. However, the vet ratings didn't always match up with the results.

For example, Maltese dogs tended to have a high pain sensitivity threshold or low pain tolerance (reacting quickly to stimuli), as the vet surveys predicted.

However, vets also ranked Siberian huskies as being similar in terms of a high pain sensitivity threshold, whereas these dogs were more towards the middle of the rankings and less sensitive to pain.

Labrador retrievers and golden retrievers were consistently at the top of the pain tolerance rankings (so a low sensitivity). This was again predicted by the vets, who tend to think dogs can take more pain than the general public do.

The researchers also found that dogs less likely to engage in the emotional reactivity tests sometimes had a higher pain sensitivity threshold too, but this relationship wasn't conclusive and needs further study.

"These behavioral differences might explain the different veterinarian ratings, but not actual pain tolerance between breeds," says Duncan Lascelles, a veterinary surgeon at North Carolina State University.

"This study is exciting because it shows us that there are biological differences in pain sensitivity between breeds. Now we can begin looking for potential biological causes to explain these differences, which will enable us to treat individual breeds more effectively."

In short, just because a dog is acting nervously or being reticent, it doesn't necessarily follow that it's more or less sensitive to pain. That's something that can be useful when it comes to looking after dogs in difficult scenarios – such as at the vets.

With a better understanding of exactly why certain breeds are more comfortable with pain than others, which future studies will hopefully be able to provide, it should be possible to more accurately prescribe pain relief in the future.

"On the behavioral side, these findings show that we need to think about not just pain, but also a dog's anxiety in the veterinary setting," says Gruen. "And they can help explain why veterinarians may think about certain breeds' sensitivity the way they do."

The research has been published in Frontiers in Pain Research.