Fungi may not have ears, but their growth appears to be tuned to the noises of their surroundings.

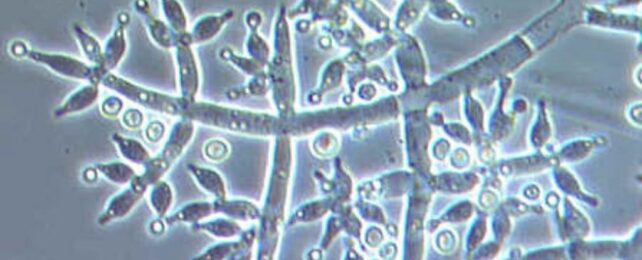

When a high-frequency monotone crackle, like that of radio static, is played to the fungus species, Trichoderma harzianum, researchers have found the organism grows and produces spores much faster than is typical – almost as if it were feeding on the white noise.

That's an important finding, because T. harzianum is present in nearly all soils, and it is known to colonize plant roots and enhance their growth. On farms, this species can actually parasitize pathogenic fungi, which can hurt plants.

It's, therefore, possible that by playing certain sounds, conservationists could promote healthier soils in numerous habitats and agricultural settings around the world.

"We strive to find novel ways to speed up and improve levels of beneficial fungi and other microbes in degraded soil," explains microbial ecologist Jake Robinson, who led the research at Flinders University in Australia.

He and his team hope their investigations will have "wide-ranging benefits for restoring degraded landscapes and farming land to feed the world."

In experiments, researchers played 30 minutes of white noise to petri dishes of T. harzianum, kept in soundproofed chambers, for five days.

Compared to petri dishes that were kept in silence, those that were exposed to white noise showed the greatest growth.

More research is needed to figure out how this particular soil fungus is growing faster in the presence of white noise, and whether the same effect occurs outside of the lab. It's also unclear if the improved growth of fungi boosts plant or bacterial growth, in turn.

"Despite the need for further investigation into potential unintended consequences, our study marks an important stride toward leveraging sound as an innovative tool to help promote ecosystem restoration," writes the team at Flinders.

This isn't the first time scientists have tried treating fungi with sound. If oyster mushroom farmers 'treat' their mycelium with certain sounds every five days, evidence suggests it can boost the growth of the fruiting bodies.

But sound can also be detrimental.

In 2020, researchers figured out that the hum of refrigerators was increasing the growth of a pathogenic fungus that rots fruits and vegetables around the world. In the lab, playback of these high-frequency fridge noises increased rot by up to 18 percent.

In the case of T. harzianum, it's unclear why the fungi is growing faster and producing more spores in the presence of white noise.

Robinson and his team suspect that the sound waves are mechanically activating the organism's receptors. This mechanical signal is then translated into either an electrical voltage or a biochemical signal.

If it's a biochemical signal, this could alter the fungi's gene expression or cell production.

If it's converted into an electrical signal, which Robinson and his colleagues say is less likely, this could allow the fungi to communicate better. The nerve-like electrical activity of fungi has recently been compared to human speech, and it could help protect the organism's integrity.

This is an avenue of investigation that is still in its earliest stages. But evidence increasingly suggests that fungi, bacteria, and plants can all respond to sound in intriguing and possibly useful ways.

The study was published in Biology Letters.