The World Health Organisation said this week it may be 18 months before a vaccine against the coronavirus is publicly available.

Let's explore why, even with global efforts, it might take this long.

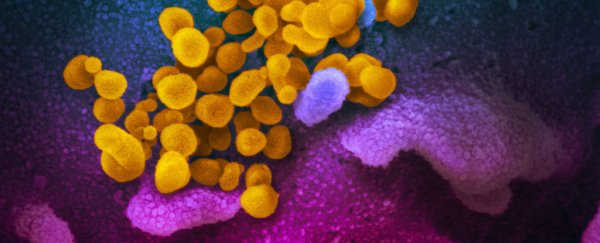

China shared publicly the full RNA sequence of the virus – now known as SARS-CoV-2 rather than COVID-19, which refers to the disease itself – in the first half of January.

This kickstarted efforts to develop vaccines around the world, including at the University of Queensland and institutions in the US and Europe.

By late January, the virus was successfully grown outside China for the first time, by Melbourne's Doherty Institute, a critically important step. For the first time, researchers in other countries had access to a live sample of the virus.

Using this sample, researchers at CSIRO's high-containment facility (the Australian Animal Health Laboratory) in Geelong, could begin to understand the characteristics of the virus, another crucial step in the global effort towards developing a vaccine.

Vaccines have historically taken two to five years to develop. But with a global effort, and learning from past efforts to develop coronavirus vaccines, researchers could potentially develop a vaccine in a much shorter time.

Here's why we need to work together

No single institution has the capacity or facilities to develop a vaccine by itself. There are also more stages to the process than many people appreciate.

First, we must understand the virus's characteristics and behaviour in the host (humans). To do this, we must first develop an animal model.

Next, we must demonstrate that potential vaccines are safe and can trigger the right parts of the body's immunity, without causing damage. Then we can begin pre-clinical animal testing of potential vaccines, using the animal model.

Vaccines that successfully pass pre-clinical testing can then be used by other institutions with the capacity to run human trials.

Where these will be conducted, and by whom, has yet to be decided. Generally, it is ideal to test such vaccines in the setting of the current outbreak.

Finally, if a vaccine is found to be safe and effective, it will need to pass the necessary regulatory approvals. And a cost-effective way of making the vaccine will also need to be in place before the final vaccine is ready for delivery.

Each of these steps in the vaccine development pipeline faces potential challenges.

Vaccine for new coronavirus 'COVID-19' could be ready in 18 months: WHO https://t.co/8GrGDZf1AN pic.twitter.com/c7KQWxyTn3

— Reuters (@Reuters) February 11, 2020

Here are some of the challenges we face

The international Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations has engaged our team in those first two steps: determining the characteristics of the current virus, then pre-clinical testing of potential vaccines.

While Melbourne's Doherty Institute and others have been instrumental in isolating the novel coronavirus, the next step for us is growing large amounts of it so our scientists have enough to work with. This involves culturing the virus in the lab (encouraging it to grow) under especially secure and sterile conditions.

The next challenge we face is developing and validating the right biological model for the virus. This will be an animal model that gives us clues to how the coronavirus might behave in humans.

Our previous work with SARS (severe acute respiratory syndrome) has given us a good foundation to build on.

SARS is another member of the coronavirus family that spread during 2002-03. Our scientists developed a biological model for SARS, using ferrets, in work to identify the original host of the virus: bats.

SARS and the new SARS-CoV-2 share about 80-90 percent of their genetic code. So our experience with SARS means we are optimistic our existing ferret model can be used as a starting point for work on the novel coronavirus.

We will also explore other biological models to provide more robust data and as a contingency.

What good will a vaccine be if the virus mutates?

There's also the strong possibility that SARS-CoV-2 will continue to mutate.

Being an animal virus, it has already likely mutated as it adapted – first to another animal, and then jumping from an animal to humans.

Initially this was without transmission among people, but now it has taken the significant step of sustained human-to-human transmission.

As the virus continues to infect people, it is going through something of a stabilisation, which is part of the mutation process.

This mutation process may even vary in different parts of the world, for various reasons.

This includes population density, which influences the number of people infected and how many opportunities the virus has to mutate. Prior exposure to other coronaviruses may also influence the population's susceptibility to infection, which may result in variant strains emerging, much like seasonal influenza.

Therefore, it's crucial we continue to work with one of the latest versions of the virus to give a vaccine the greatest chance of being effective.

All this work needs to be done under stringent quality and safety conditions, to ensure it meets global legislative requirements, and to ensure staff and the wider community are safe.

Other challenges ahead

Another challenge is manufacturing proteins from the virus needed to develop potential vaccines. These proteins are specially designed to elicit an immune response when administered, allowing a person's immune system to protect against future infection.

Fortunately, recent advances in understanding viral proteins, their structure and functions, has allowed this work to progress around the world at considerable speed.

Developing a vaccine is a huge task and not something that can happen overnight. But if things go to plan, it will be much faster than we've seen before.

So many lessons were learned during the SARS outbreak. And the knowledge the global scientific community gained from trying to develop a vaccine against SARS has given us a head-start on developing one for this virus. ![]()

Rob Grenfell, Director of Health and Biosecurity, CSIRO and Trevor Drew, Director of the Australian Animal Health Laboratory (AAHL), CSIRO.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.