It's been centuries since a wolf's howl was heard across the Scottish Highlands, but a team of researchers thinks it's time to bring back these much-maligned predators.

Doing so, their simulations have found, could return native woodlands to the country and pull carbon from the air.

Wolves (Canis lupus) were totally eradicated by human hunting in Scotland, with tradition claiming the last wolf was killed about 250 years ago (although it's difficult to be sure of the exact year, amid local myth and legend).

Around that time, the Jacobite rebellion of 1745 fundamentally changed much of the nation's land use. Woodland was cleared, and large shooting estates were established.

Eradicating this apex predator unraveled entire woodland ecosystems because the wolf's prey, red deer (Cervus elaphus), could multiply unabated.

Recent estimates suggest up to 400,000 red deer are out there right now, trampling and gnawing at the young saplings of trees that, in their absence, could grow into woodlands. Today, Scotland has native woods covering less than 4 percent of its surface, one of the lowest levels in Europe.

It's a textbook case of a predator as a 'keystone' species: a brick in the arch that holds its entire structure in place. In the US, reintroduction of wolves to a number of nationally managed ecosystems has been successful, most famously in Yellowstone National Park.

In theory, returning wolves to Scotland's wilds should help reduce the deer numbers, giving the woodland a chance to make a comeback.

"There is an increasing acknowledgment that the climate and biodiversity crises cannot be managed in isolation," says lead author and environmental scientist Dominick Spracklen from the University of Leeds.

"We need to look at the potential role of natural processes such as the reintroduction of species to recover our degraded ecosystems and these in turn can deliver co-benefits for climate and nature recovery."

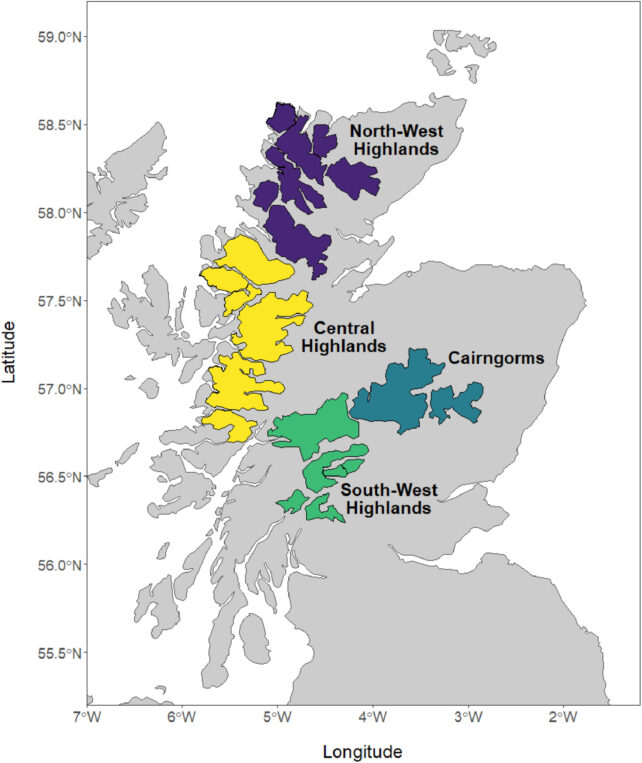

The scientists' simulations suggest that a reintroduction in four key areas of Scotland could lead to a population of around 167 wolves, enough to reduce the density of deer populations in those areas to just four per square kilometer (0.4 square mile) in as little as two decades.

Each wolf, they estimate, has the potential to bring back enough woodland to absorb 6,080 metric tons (6,702 US tons) of carbon dioxide each year. In today's carbon market, that's worth about US$195,000.

The resulting expansion of native woodlands would sequester 100 million metric tons of CO2 over 100 years, their model suggests, "sufficient to make an important contribution to national climate targets".

"Large-scale expansion of woodlands, facilitated through the return of wolves, can contribute to national climate targets and could provide potential economic benefits to landowners and communities through carbon finance," the authors write.

But understandably, there are safety concerns that need to be considered – it's an intensely divisive topic, and for good reason.

"Human-wildlife conflicts involving carnivores are common and must be addressed through public policies that account for people's attitudes for a reintroduction to be successful," says ecologist and farmer Lee Schofield, who co-authored the paper.

The researchers believe lessons learned from the US and European wolf reintroductions will help here; and, while there's no denying the basis for wolves' fearful reputation, ecosystem collapse and extreme climate change are hardly toothless alternatives.

"This substantial carbon sequestration and the potential financial benefit related to wolf reintroduction may influence landowner and land manager perspectives around large carnivores," the team writes.

The research was published in Ecological Solutions and Evidence.