The haunting howls of wolves fell mostly silent across America's West by the 1930s.

Their loss to the region has been largely overlooked by humans, even in our scientific research, a new review finds, but the impact of their absence is written loudly in the missing trees.

"Researchers generally agree that the loss of wolves and other large predators, followed by increased browsing by elk (Cervus canadensis), was the main cause for the decline in woody plant communities in many Western parks," write Oregon State University ecologist William Ripple and colleagues in their new paper.

This is another example of how everything on our living planet is tightly interconnected and how we fail to consider these vital links.

Ripple and team reviewed 96 ecological studies that took place between 1955 and 2021, within 11 of the region's national parks. They found only 39 of these studies considered the absence of the region's top predator, the gray wolf (Canis lupus).

"Studying an altered ecosystem without recognizing how or why the system has changed over time because of the absence of a large predator could have serious implications… like diagnosing a sick patient without a baseline health exam," explain the researchers.

"Various national parks in the western United States, which are considered the crown jewels of American wilderness, lack their apex predators, resulting in them being shadows of their supposed ecological integrity."

Loss of an ecosystem's apex predator causes domino effects through an ecosystem's food chain known as trophic cascades. As ecosystems can be such complex messes of interactions it's not always easy to see how trophic cascades will play out, particularly given they can be context-dependent.

So not every trophic cascade is found in each landscape, even if the same species are present. Reintroducing lost species, like the return of wolves to Yellowstone National Park, can't necessarily repair all the broken connections either, once the cascade of changes have taken place.

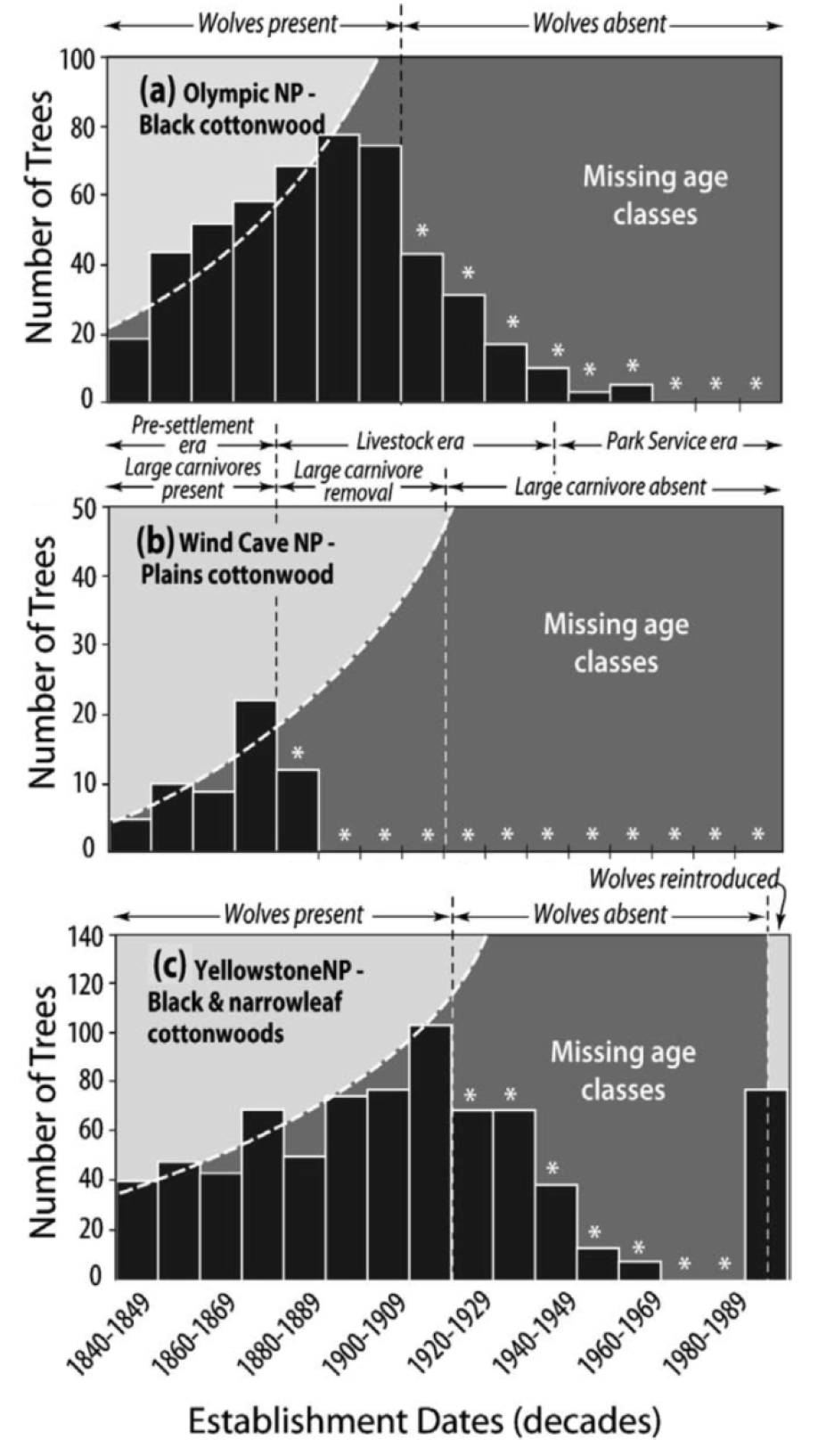

But historical records across the 11 parks reveal declines in several tree species, including black (Populus trichocarpa) and plains (Populus deltoides) cottonwoods, since wolves were eradicated.

Not only has removal of wolves messed with the web of connections stemming from their predation on deer, it's impacted the ecosystem interactions around coyotes (Canis latrans) as well.

"Wolves can reduce coyote populations, thereby mediating their predation of prey and smaller-predator populations, such as rodents, ungulates, small carnivores, leporids, and birds," write Ripple and team.

This includes greater predation of threatened and endangered species, a particularly concerning consequence amidst the sixth mass extinction.

The same scenario is occurring in the oceans, where the absence of reef sharks means too many green turtles are gorging on vital CO2 sequestering seagrass meadows, and in Australia, where the widespread eradication of dingoes means smaller predators like foxes and cats are having their fill of predator-naive marsupials.

Kangaroos are now also overabundant thanks to the lack of dingoes, joining deer in the top ten most abundant wild animals by biomass. Ripple previously found there are almost six times more deer in areas without wolves compared to areas with them.

Ecosystem restoration is more critical than ever as our destructive impacts on our living biosphere accelerate. But to have any success, it is crucial that we better understand the interactions that govern these environments in their historical functioning state, the researchers urge.

"We hope our study will be of use to both conservation organizations and government agencies in identifying ecosystem management goals," says Ripple.

This study was published in Bioscience.