Cognitive decline is a too-common feature of old age among those born with Down syndrome.

Though the reasons aren't well understood, having an extra copy of chromosome 21 seems to hasten the neurodegeneration that puts individuals at risk of developing Alzheimer's disease.

For the last decade of her life, and beyond, a US woman with Down syndrome mystified researchers by showing all of the physical signs of having Alzheimer's with none of the expected symptoms.

The team behind her recent case study hopes that by understanding the nature of the woman's unusual situation, researchers might gain deeper insights into the manifestation of dementia.

"If we can identify the genetic underpinnings or lifestyle factors that allowed her brain to function well despite the pathology, we may uncover strategies that could benefit others," says University of California, Irvine neuroscientist Elizabeth Head.

"This study shows how just one person's participation in research can lead to profound discoveries."

While it isn't hard for specialists to find older cognitively healthy individuals with Alzheimer's pathology, it's less common to find people with Down syndrome who aren't affected by their neurodegeneration.

Most develop early signs of dementia as they approach their mid-50s, with those in their 60s experiencing a 90 percent chance of developing the clinical features of either mild cognitive decline or full dementia.

The Alzheimer Biomarker Consortium–Down Syndrome was established in 2015 to better understand the links between the two conditions by examining the physical markers of Alzheimer's among people born with trisomy 21.

By the time she was enrolled in the consortium, the remarkable patient who showed no signs of cognitive decline in spite of being in her sixties had already participated in two separate longitudinal studies funded by the US National Institutes of Health, providing a wealth of clinical and psychological data.

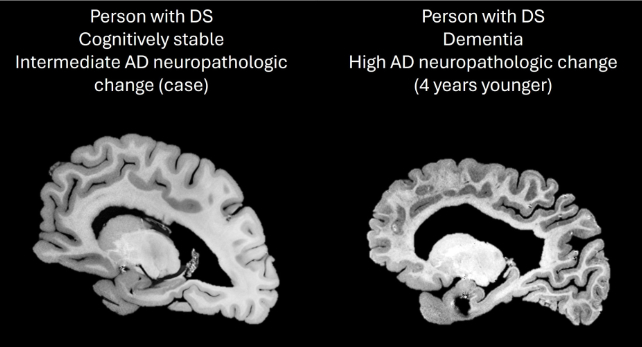

Decades of tests had shown that she had both Down syndrome and an intermediate level of Alzheimer's. Physical examinations demonstrated elevated levels of amyloid in her brain, signature ratios of proteins in her spinal fluid, and critical changes in her neurological wiring synonymous with dementia.

Yet a battery of psychological tests indicated the woman's mind had remained relatively sharp for the entire period of her testing. In her daily life, the woman did her cooking and shopping, with no outward signs of change in behavior or social interactions prior to her passing.

"Before she passed away, all the clinical assessments in our years of studying her indicated that she was cognitively stable, which is why this case is so fascinating," says consortium investigator Jr-Jiun Liou, a neurologist with the University of Pittsburgh.

"Despite her brain's pathology indicating Alzheimer's, we think that her cognitive stability could have been attributed to her high education level or underlying genetic factors."

Though her IQ was below average, the woman had attained a private education through childhood and into adolescence at a school that had been licensed to teach students with intellectual disabilities.

Physiologically, there were various factors that could have also given her brain a margin of resistance against Alzheimer's degeneration, including a potential 'reserve' in extra brain tissue, and genes that helped cope with accumulations of damaged proteins.

There is also an unanswered question of the nature of her trisomy. In some cases, those with characteristics of Down syndrome have a form of mosaicism, where some cells have just the typical pair of chromosome 21.

Should that be the case here, it's possible the incomplete spread of a third chromosome 21 through the body could be significant.

On its own, the study raises some questions.

While this woman's case is unusual, combined with other investigations of similar cases, her remarkable story could one day help others with Alzheimer's remain cognitively strong well into old age.

This research was published in Alzheimer's & Dementia.