The human brain is super sensitive to any sort of pattern that resembles a face, which is why we so often 'catch the eye' of inanimate objects glaring, grinning, or gaping back at us.

Now, psychologists in Australia have shown that the tendency to see faces that aren't really there, called face pareidolia, may be heightened in those who have recently given birth.

The findings, which come from the University of Queensland (UQ) and the University of the Sunshine Coast, are the first to suggest that face pareidolia fluctuates throughout adulthood, potentially increasing and decreasing with fluctuations in certain hormone levels.

In the past, scientists have found that the tendency towards face pareidolia does correlate with age and severity of conditions like Parkinson's and dementia.

What's more, when artificial oxytocin is administered to humans, the hormone can increase sensitivity to various facial signals, and levels of oxytocin naturally climb over an individual's lifetime.

To explore these changes further, researchers turned to women in the postpartum period, when oxytocin levels are at their peak.

The team, led by UQ psychologist Jessica Taubert, tested how a postpartum group sees illusory faces compared to pregnant individuals and those who have never been pregnant.

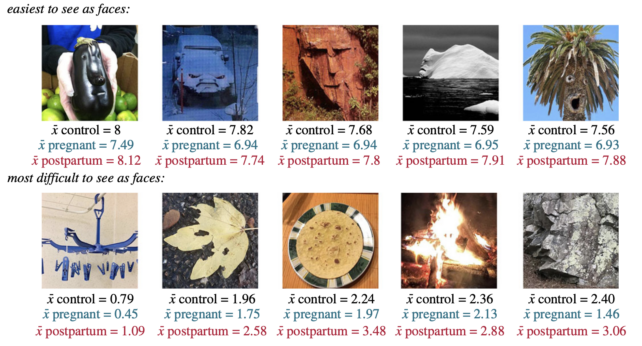

The online study included more than 400 female participants, who were shown several hundred photographs of real human faces, objects with faces, and objects without faces.

For each photo, participants were asked how easily they could see a face in the photo, using a scale of 1 (no, I don't see a face) to 10 (yes, I definitely do see a face).

Ultimately, those women who had had a child in the past year reported seeing all the illusory faces more easily than women who had never been pregnant and women who were currently pregnant.

"In sum, we have unearthed preliminary evidence that postpartum women are more susceptible to face pareidolia than pregnant women," Taubert and colleagues write.

"Our findings contribute to this growing literature by suggesting that our sensitivity to face pareidolia is heightened during early parenthood, possibly promoting social bonding, which is thought to be critical in maternal-infant dyads."

The study is only preliminary as it did not directly measure oxytocin levels among participants. Postpartum women were simply assumed to have higher levels of this hormone than the other groups, as this has been found before.

Further research will, therefore, need to confirm the exact role oxytocin levels play in facial recognition and how its effects might differ between sexes and ages.

Taubert hopes that by continuing research on pareidolia, psychologists can learn more about how the human brain detects and recognizes social cues.

One day, we might even be able to use this information to test for abnormalities in cognitive processing.

The study was published in Biology Letters.