Researchers in Japan have found a way to make the 'wonder material' graphene superconductive - which means electricity can flow through it with zero resistance. The new property adds to graphene's already impressive list of attributes, like the fact that it's stronger than steel, harder than diamond, and incredibly flexible.

But superconductivity is a big deal, even for graphene, because when electricity can flow without resistance, it can lead to significantly more efficient electronic devices, not to mention power lines. Right now, energy companies are losing about 7 percent of their energy as heat as a result of resistance in the grid.

Before you get too excited, this demonstration of superconductivity in graphene occurred at a super cold -269 degrees Celsius, so we're not going to be making power lines out of graphene any time soon.

But what is exciting, is that this research suggests that graphene could be used to build nano-sized, high-speed electronic devices. Just imagine all the electricity we could save with computers that rely on tiny graphene circuity, capable of zooming electrons around without wasting energy as heat.

For those who aren't already familiar with graphene, the material is a one-atom-thick layer of graphite (the stuff that makes up your pencils), which is made up of carbon atoms arranged in a hexagonal honeycomb patterns.

The electrons inside graphene are already pretty special, because they're able to take on a special state called Dirac-cone, where they behave as if they have no mass. That makes them very speedy, but even though graphene is a very efficient conductor, it's not a superconductor, which is a state that requires zero resistance.

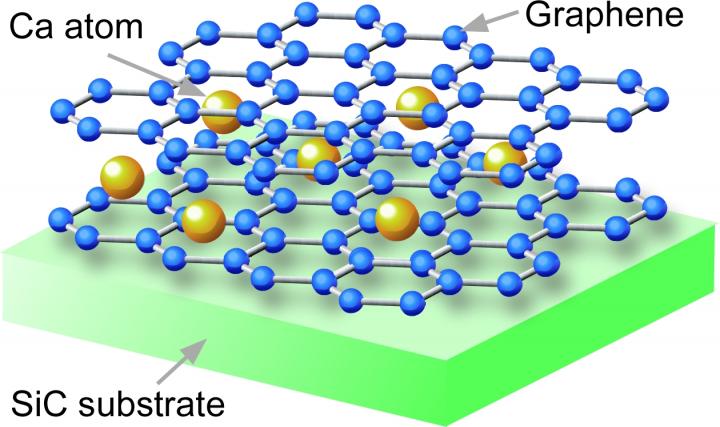

Now a team from Tohoku University and the University of Tokyo have managed to achieve superconductivity by creating two graphene sheets and inserting calcium atoms between them - sort of like a calcium sandwich, with graphene acting as the bread.

Takashi Takahashi

Takashi Takahashi

These graphene sheets were grown on a silicon carbide crystal (the SiC substrate in the image above), and the team was able to show that when the temperature gets to around 4 Kelvin, or -269 degrees Celsius, the electrical conductivity of the material rapidly drops - a clear indication of superconductivity.

Superconductivity generally relies on electrons not repelling each other, as they usually do, and pairing up instead, so they can flow through materials effortlessly. As you can imagine, when that happens in a material with electrons that are already acting like they have no mass, scientists get pretty excited.

"This is significant because electrons with no mass flowing with no resistance in graphene could lead to the realisation of an ultimately high-speed nano electronic device," Tohoku University explains.

Just last year, researchers were able to make graphene superconductive by coating it in lithium, but the Japanese team has now managed to achieve the same thing while keeping the material in its original state.

They were also able to show that superconductivity didn't occur when the graphene bilayers were on their own, or when they were coated in lithium, suggesting that the calcium atoms are what's important to the process - although the researchers admit they still don't know what phenomenon is taking place in graphene to achieve superconductivity, so there's more work to be done.

But if they can figure out what's going on, they might be able to tweak the process and find a way to achieve superconductivity in graphene at higher temperatures, and that would be huge.

As we mentioned before, graphene is unlikely to be used to build power lines - there are more promising high-temperature superconductors that would be better suited to that job - but it could revolutionise our computers.

"The latest results pave the way for the further development of ultrahigh-speed superconducting nano devices," says Tohoku University, "such as a quantum computing device, which utilises superconducting graphene in its integrated circuit."

We're looking forward to seeing what amazing thing graphene does next.

The research has been published in ACS Nano.