Supersolids are a strange quantum state of matter that combines properties of solids and liquids.

Now they've gotten even more mind-bending, as scientists have transformed light itself into a supersolid. It's a breakthrough that could lead to new quantum and photonic technologies.

Beyond the everyday solids, liquids, gases, and plasmas, an entire zoo of exotic states of matter exists. Long theorized but only recently created, a supersolid has a crystalline structure like a regular solid, but it can also, counterintuitively, flow freely like a fluid.

"We can imagine the supersolid as a fluid composed of coherent quantum droplets periodically arranged in space," says atomic and optical physicist Iacopo Carusotto from the University of Trento in Italy.

The droplets, Carusotto explains, "are able to flow through an obstacle without undergoing perturbations, maintaining their spatial arrangement and mutual distance unchanged as happens in a crystalline solid."

Supersolids have previously only ever been made out of atoms, but the team led by scientists at the National Research Council (CNR) in Italy has now created one using photons for the first time.

"Realizing this exotic state of condensed matter in a fluid of light flowing in a semiconductor nanostructure will allow us to investigate its physical properties in a new and controlled way and perhaps to be able to exploit its unique characteristics for possible applications in new light-emitting devices," says condensed matter physicist Dario Gerace from Italy's University of Pavia.

Understanding exactly what's happening here can be tricky. Scientists didn't just pluck free-flying photons out of the air and coax them into an exotic state of matter – light isn't matter, after all, it's energy.

To make it work, the researchers had to couple the photons to matter. The photons came from a laser, which was beamed onto a semiconductor of gallium arsenide that provided the matter part of the equation. The photons interact with excitations in the material to create quasiparticles called polaritons.

Similar setups have been used in the past to turn light into a superfluid. Making it into a supersolid takes a few extra steps.

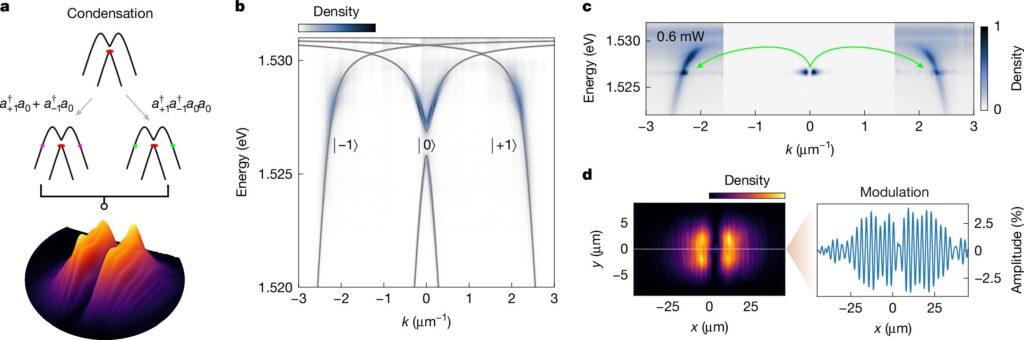

The gallium arsenide had a particular structure designed to manipulate the photons into three different quantum states.

At first, the photons settle into a state with zero momentum, but as this state 'fills up', pairs of photons begin to spill into the two adjacent states. This causes the polaritons to condense into what the team calls a bound state in the continuum (BiC).

Constraining polaritons to each state within the semiconductor is what gives them the spatial structure of a solid, while their natural ability to flow without friction makes them a superfluid. The properties of both together should make the whole system a supersolid.

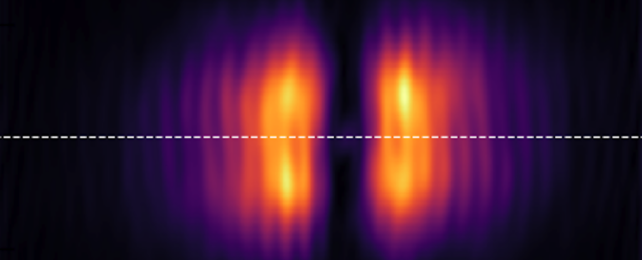

To confirm this was the case, the team then had to check for some of the telltale signs. Mapping out the density of the photons reveals two towering peaks with a chasm in the center. But on top of this lies a particular pattern of modulation, which indicates that the translational symmetry is broken – a characteristic of supersolids.

Next, they used interferometry to measure the quantum state of the system, and ensure that it was coherent locally, in each state component, and globally across the whole system. And sure enough, that fragile order held together, adding further evidence of the creation of a supersolid.

The team says that this represents an entirely new way to make the strange state of matter.

"This work not only demonstrates the observation of a supersolid phase in a photonic platform, but also opens the way to the exploration of quantum phases of matter in non-equilibrium systems," says physicist Daniele Sanvitto, of the CNR's Institute of Nanotechnology.

"This is particularly significant because this approach has the potential to bridge the gap between fundamental science and practical applications."

The research was published in the journal Nature.