The oldest known lizard has reclaimed its crown clade. A contentious fossil has been re-analyzed by paleobiologists and declared the earliest known member of the lizard-snake group.

The critter at the center of the debate is known as Cryptovaranoides microlanius, meaning 'hidden lizard, small butcher'. The second half refers to its size and diet, while the first is a reference to the fossil spending almost 70 years in a storage room before being scientifically described.

In 2022, University of Bristol scientists finally studied the skeleton and placed it within Squamata, the reptile order that contains all lizard and snake species. With the specimen dating back at least 202 million years, that would push the origin of the group back by 35 million years or so.

While the move was controversial, the researchers believed they'd done their due diligence in their physiological analysis of the species.

"We were therefore surprised, perhaps even shocked, that in 2023 another team of academics suggested that Cryptovaranoides was not a lizard or even a lizard relative, but in fact an archosauromorph, more closely related to crocodilians and dinosaurs," says vertebrate paleontologist Michael Benton.

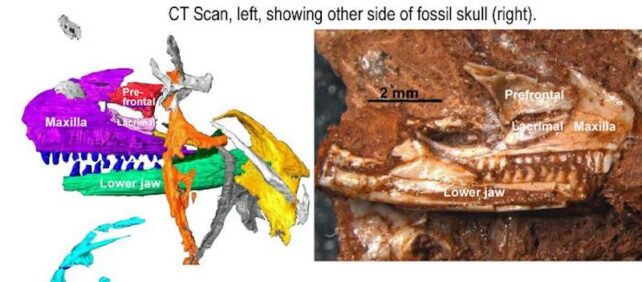

In a new paper, the team has taken a closer look at the fossil, setting out to address the critics' concerns. X-rays, CT scans, and phylogenetic analysis provide extra evidence to support the original conclusion: Cryptovaranoides is indeed a squamate, meaning the group dates back to the late Triassic period.

"All the details of the skull, the jaws, the teeth, and the limb bones confirm that Cryptovaranoides is a lizard, not an archosauromorph," says Benton. "In our new paper, we provide great detail of every criticism made and we provide more photographs of the specimen and 3D images from the scans, so everyone can check the detail."

The specifics of the dispute get quite technical, but in the new paper, the Bristol scientists methodically address the issues raised by the other team, led by Yale evolutionary biologist Chase Brownstein.

They start by going through the major errors the rival team made in observations of the fossil. Certain features in the limbs and skull, which suggest a squamate, were apparently missed by Brownstein et al., and the Bristol team highlights them with new images. Next, the team dives into a list of bone features that back up their original classification.

But the biggest rebuttal comes in the form of a phylogenetic analysis. This involves figuring out where a species belongs in the evolutionary tree, based on the traits it shares with related organisms.

"This is where we code hundreds of anatomical features in Cryptovaranoides and other modern and fossil lizards, as well as various archosauromorphs," says Bristol geologist David Whiteside.

Through this process, the team identified three main features that place Cryptovaranoides in the Lepidosauria superorder that contains Squamata (but not archosauromorphs).

Ten features fit it within the Pan-Squamata clade, and two specifically place it in Squamata. Finally, four features focus it in on Anguimorpha, a suborder of squamates that includes monitor lizards, beaded lizards, and Komodo dragons.

On the other hand, the team argues that placing it in archosauromorpha, as Brownstein et al. proposed, would require rejecting all of the above features. The few things that could indicate it belongs in that classification were mistakes made by the other team, the Bristol researchers say.

"We ran the analysis time after time, and it gave our original result, that the little Bristol reptile is indeed the world's oldest modern-type lizard," says Whiteside.

Either way, this humble reptile had no idea what debate it might spark 200 million years later, as it scurried under the feet of the early dinosaurs.

The research was published in the journal Royal Society Open Science.