A ghastly bout of food poisoning isn't an experience to forget. The commonly studied microscopic nematode Caenorhabditis elegans not only ensures it remembers, it genetically embeds the threat of skanky meals into its kids to force them to stay clear as well.

And if by some misfortune one of those worms goes belly-up anyway? The warning encoded in RNA can leak out of their disintegrating body, potentially to be picked up by any passing member of the species.

This remarkable means of memory transfer was spotted by researchers from Princeton University's Murphy Lab in the US as a part of a series of studies on inherited behaviors in the nematode.

Due to the existence of a fairly strict barrier between the germ cells that give rise to a new generation and the parent's own body cells, it was once believed events affecting a parent's physiology couldn't be imprinted on their offspring.

That view has gone out the window with discoveries of environmental stresses in animals like C. elegans changing the way genes are switched on not only in their offspring, but in their offspring's own children… and so on, for generations down the line.

It's not just a worm thing, either. Genes in the offspring of fruit flies and even mice can be tweaked by cues in their parent's environment, effectively changing the biological functions of future generations.

Last year, researchers at molecular biologist Coleen Murphy's lab published their findings on C. elegans reactions to consuming the bacterium Pseudomonas aeruginosa – an appealing food source that quickly turns nasty in their digestive system.

The team discovered that worms absorbed strands of RNA from their toxic meal through their intestines, among which was a stretch of non-coding RNA called P11.

This slither of nucleic acid was found to bind to a corresponding code in the worm's genome – a gene called maco-1 – which was already known to play a role in sensory perception. As a result, the worm 'learns' to steer clear of P. aeruginosa in the future.

Amazingly, this behavioral shift also affects a mother worm's descendants, teaching at least the next four generations to avoid this particular microbial meal as well.

This latest experiment demonstrates that genetic memory isn't strictly a family affair, with evidence that it can be transmitted laterally from worm to worm.

Tragically, the teacher has to be pulped first.

"We found that one worm can learn to avoid this pathogenic bacterium and if we grind up that worm, or even just use the media the worms are swimming in, and give that media or the crushed-worm lysate to naïve worms, those worms now 'learn' to avoid the pathogen as well," says Murphy.

Investigations of nematodes incapable of learning this avoidance trick suggested that in spite of maco-1's established role in avoiding P. aeruginosa, the gene's presence alone couldn't explain why the behavior was inherited. Something else was happening.

So the team went on the hunt for other factors behind the quirky neurological adaptation.

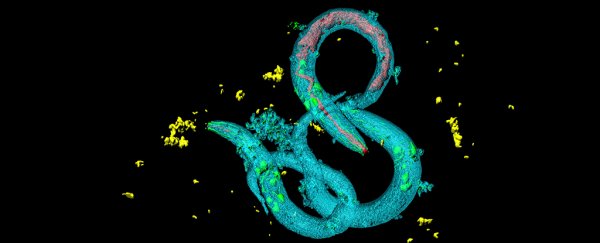

(Murphy Lab)

(Murphy Lab)

Chief suspect was an itinerant 'jumping' gene called Cer1, already known to have the right characteristics to move from one part of a genome to another like a virus.

"What we discovered is that a retrotransposon called Cer1 that forms viral-like particles seems to carry a memory not only between tissues (from the worm's germline to its neurons) but also between individuals," says Murphy. Worms that naturally lacked Cer1, or had it edited out, simply couldn't resist taking a nibble of P. aeruginosa.

This whole learning experience isn't without its risks. The retrotransposon's jumping behavior can also cause harm as it inserts itself into parts of the animal's genome, suggesting there has to be a benefit to its costs.

Fascinating as they are now, hints that behavior-altering experiences can be inherited would have been surprisingly controversial half a century ago, when American animal psychologist James V. McConnell shot to fame – and infamy – over suggestions that flatworms could inherit memories by consuming other, more educated flatworms.

McConnell's chapter in the history of biology has since influenced debate over the permeability of that barrier between parent and child, and whether one generation's experiences of the world can directly affect the way the next approaches it.

The extent to which this might happen in humans is still being explored, yet there are tantalizing signs we're not exempt, either.

This research was published in Cell.