Extreme heat is the most dangerous risk posed by climate change in Australia, and it's not just taking a physical toll on the population. There may also be a mental cost going unaddressed.

A new study suggests high temperatures Down Under are already impacting living and working conditions, and as climate change worsens, these challenges may increase the burden of mental and behavioral disorders (MBDs).

MBDs encompass a whole variety of issues, including anxiety disorders, depressive disorders, bipolar affective disorder, schizophrenia, alcohol and drug use disorders, and other mental and substance use disorders.

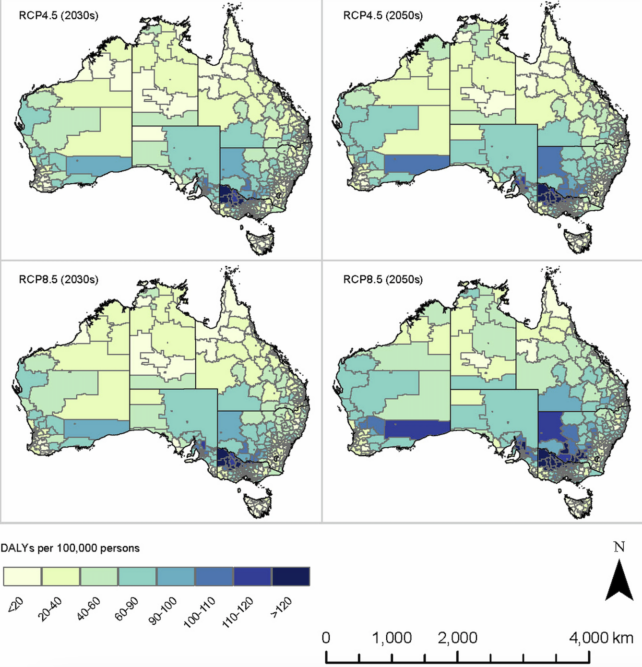

According to the recent projections, if global warming is stalled below 3 degrees Celsius by 2100 (compared to pre-industrial levels), the relative burden of MBDs may increase by 11 percent in the 2030s and 27.5 percent in the 2050s.

If no major efforts are made to mitigate global warming and the climate crisis escalates, the burden of MBD could increase by nearly 49 percent come 2050.

"The detrimental impacts of climate change on good mental health and emotional states have been increasingly recognized worldwide, and it's only going to get worse unless we act," says senior author Peng Bi, a researcher of environmental health from the University of Adelaide.

"From mild distress to serious conditions like schizophrenia, rising temperatures are making things harder for millions. Young people, who often face these issues early in life, are especially at risk as the climate crisis worsens."

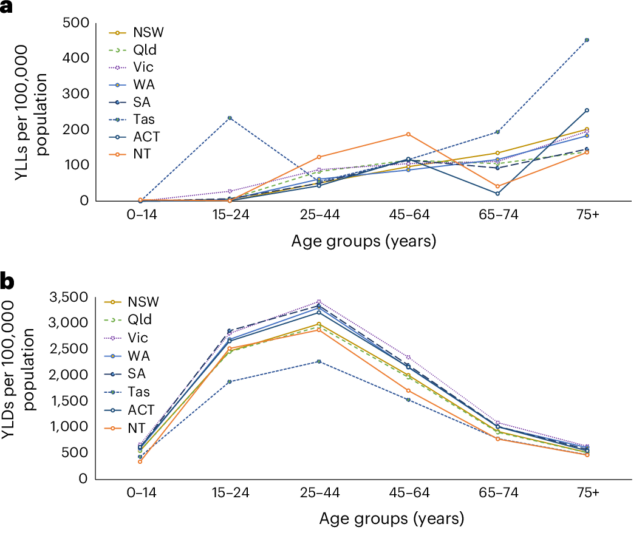

The new estimates from Bi and colleagues are based on health data from all states and territories in Australia between 2003 and 2018. The dataset shows that MDS-related hospitalizations and emergency room visits generally increased with high temperature events.

These heatwaves were rarely fatal for those with MBDs, but they did significantly impact a person's years spent in full health.

In a 2008 heatwave that hit Adelaide, for instance, the 15-day-long disaster was linked to a 64 percent increase in MDS-related hospitalizations among children, and a 10 percent increase in MDS-related hospitalizations among those aged 75 and over.

Scientists aren't sure how extreme heat may impact mental health, but it's possible that changes in blood temperature can affect how much oxygen gets to the central nervous system. High temperatures may also impact sleep patterns and stress responses, all of which can have impacts on mental health.

Today, it is estimated that nearly 44 percent of Australians aged 16 to 85 experience MBDs at some point in their lives. That's roughly 8.6 million people.

While the annual absolute risk of heat-related hospitalizations is low for this group of individuals, if global warming trends continue, that risk could double in the years to come, jumping from 1.8 percent to 2.8 percent by 2050. That increase is greater than what could be attributed to population growth or an aging population, raising concerns climate change will exact a toll.

That's an interesting finding, as it suggests the mental health of older people is not necessarily more vulnerable to heatwaves. Recent studies have found, for instance, that young people may be more at risk of dying from higher temperatures than the very old.

Because young people are physiologically more adept at handling heatwaves, researchers suspect they may not take the same precautions. This age group is also more likely to work outside in hot conditions.

"Considering the early onset of MBDs among the current younger people, coupled with the additional mental burden arising from climate crises, it is imperative to foster resilience," write the authors of the analysis, led by public health researcher Jingwen Liu.

"This necessitates a deeper understanding of how high temperature might affect mental health, empowering public health professionals and healthcare practitioners with the necessary knowledge and tools to safeguard communities… especially as global warming is projected to persist and accelerate."

The study was published in Nature Climate Change.