New research on mice has found a possible explanation for why autoimmune diseases are more common in females, and it has to do with their extra X chromosome.

Amongst animals, females generally tend to have stronger and more robust immune systems. While this can help them to cope better with vaccines and infections, it can also cause an overactive immune response.

This means females are much more vulnerable to autoimmune diseases. In fact, women are two to three times more likely than males to develop multiple sclerosis (MS), and nine times more likely to develop lupus.

Exactly why this discrepancy exists remains a mystery. Clear biological differences between the sexes usually boil down to hormones, chromosomes, or some combination of both. But while the role of testosterone, estrogen and progesterone in autoimmunity have been reasonably well explored, the part that X and Y chromosomes play remains far more murky.

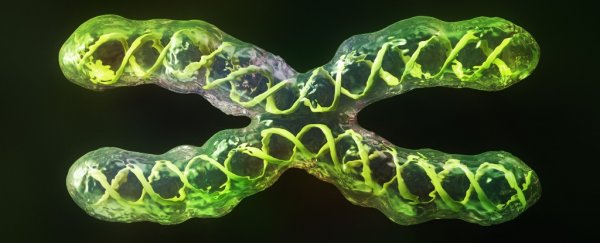

This is quite the oversight, considering that X chromosomes carry several immune-related genes, and females have two of them, one from the mother and one from the father. In comparison, males just have one X chromosome, from their mother.

Based on their work in mouse models, researchers from the University of California Los Angeles (UCLA) now think this extra X chromosome females get from the father brings a significant contribution to autoimmune issues.

Because females have two X chromosomes, the double-ups need to be balanced out through a mechanism called X inactivation: it uses DNA methylation to block the expression of certain genes.

On the inactive X chromosome, the vast majority of genes are silenced. In humans, around 15 percent of the genes can sneak through however, leading to a higher expression of X genes in females (XX) compared to males (XY).

There's also good reason to think that the silencing of some X genes might reduce the overall expression of some traits, including those that ensure the smooth functioning of the immune system. In this study, the UCLA researchers found a cluster of five genes related to the immune system on the X chromosome that are more expressed in male mice.

Analysing how immune system-related genes are expressed in males and females, the researchers then found that the X chromosome that ended up inactivated in female mice tended to come from the dad, rather than be switched off randomly.

In turn, this suggests that the X chromosomes passed from a father to a daughter have higher levels of X inactivation, which, in the case of the immune system, can dampen the expression of certain genes, possibly promoting a pro-inflammatory response in females.

Recent studies on mice and humans indicate that extra X genes may give females an immunological advantage, but it's certainly a double-edged sword.

"Our overarching hypothesis is that sex differences in the immune system are due to the balance between parental imprinting of X genes that do not escape X inactivation and X dosage effects of X genes that do escape X inactivation," the authors write.

In other words, the discrepancy in X inactivation between male and female mice could well play a role in making their immune systems work differently.

Whether or not this is the case in humans too will be challenging to prove, especially given the sheer number of immune-related genes we have, and their complex relationship with our hormones.

That said, other studies on human chromosomes have already turned up results that hint at something similar. In 2016, researchers discovered that in females, X inactivation is incomplete in the immune system's T cells and B cells, and this could play a role in autoimmune diseases like lupus.

"If you can find regulators of methylation that target these differences, you might be able to reduce the immune responses of females to treat autoimmune diseases," says neurologist Rhonda Voskuhl.

"Going forward, when one considers sex as a biologic variable in diseases, it can lead to new treatment strategies."

More research will be needed before females can start blaming their fathers for their autoimmune issues, but it certainly seems as though there's something going on with the paternal X chromosome.

This study was published in PNAS.