When you're poking around ancient ruins, you probably expect to find a few artifacts or the bits and pieces left behind by the people who lived and worked there long ago. But an archaeological site has just yielded something you might not expect if you didn't know the history of the place.

At what was once the site of Caesar's Forum in Rome, built by Julius Caesar, researchers have found a buried pit of medical waste rubbish dating back to the Renaissance in the 16th century CE, dumped by the Ospedale dei Fornari, or Baker's Hospital, that was founded in 1564 in the nearby Piazza della Madonna di Loreto.

The artifacts included medical equipment (such as glass jars for collecting urine), ceramic medicine containers, and ceramic figurines that were likely personal effects.

The research team, led by archaeologist Cristina Boschetti of Aarhus University in Denmark, believes the dump may have been used to dispose of potentially infectious objects to attempt to curtail the spread of epidemics.

It's possible that this pit could shed light on Renaissance medical waste disposal as a means of disease control in a heavily populated city.

"Defining medical dumps in archaeological contexts can be challenging because it requires an integrated approach that combines excavation data with material studies and detailed functional contextual analysis," the researchers write.

"Here, we have presented one such medical dump, excavated in the area of the Forum of Caesar in 2021."

Excavations of the site took place in 2021, during which the team found a peculiar, brick-lined chamber some 2.8 meters (9.2 feet) deep, with a layer of compact clay concealing the contents.

Further investigation revealed that the cistern dated to the 16th century CE and had been used neither before nor after the deposition of the objects found therein.

It was, the team believes, a single-use hole.

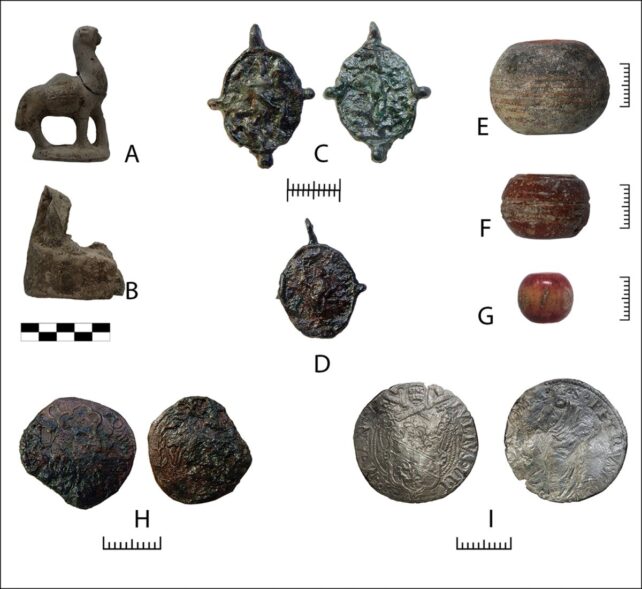

Beneath the clay, the team found a truly curious assemblage of objects: broken shards of glass and ceramic; small, intact ceramic vessels of high quality; and personal items such as terracotta figurines, devotional medals, spinning whorls, and a single bead, likely from a rosary.

There were also several lead clamps commonly used in furniture fittings and a quantity of carbonized (burnt) wood. This collection of items, dumped so haphazardly and sealed away beneath a cap of clay, might have posed more of a puzzle, but they had a remarkably similar collection of items on which to draw.

In 2009, archaeologists excavated and studied what they determined to be a medical waste disposal site associated with the hospital early in the 17th century CE.

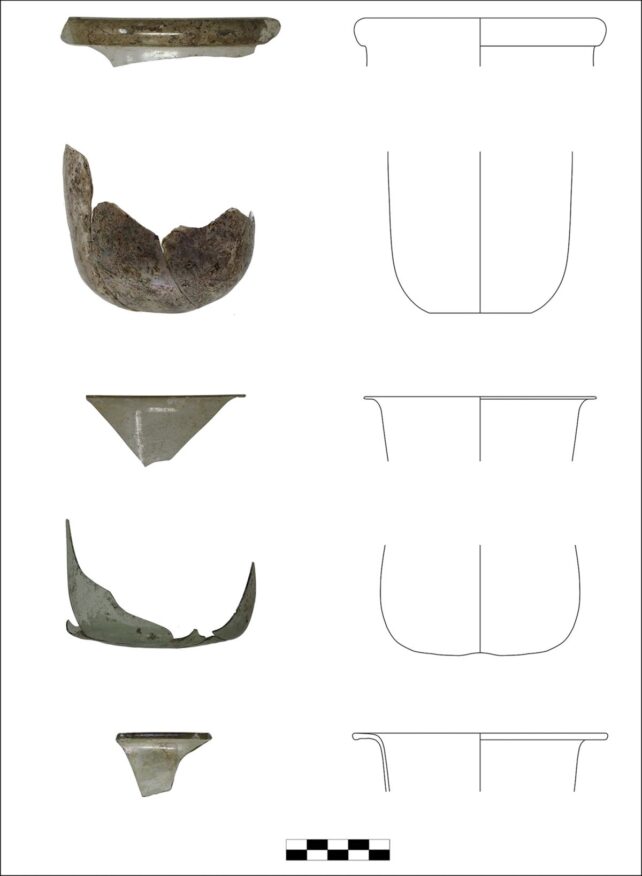

Conducting a close examination of the objects removed from the cistern, Boschetti and her colleagues counted approximately 1,200 shards of glass. Many of these, the researchers determined, were likely urine flasks, known as matula in medieval Latin sources.

"During the medieval period, the visual examination of urine – urinoscopy – had become a central diagnostic tool in medical practice and remained so into the eighteenth century," the researchers write. "The patient's urine would be poured into a flask to allow a doctor to observe its color, sedimentation, smell and sometimes even taste."

These are rare in domestic contexts but have been found in large numbers associated with medical facilities, such as the other refuse pits associated with the Ospedale de Fornari. Other items included ceramics for cooking and eating food. Each patient was given their own "kit" of such things upon admission to the hospital.

Putting the clues together, the researchers believe they point to decontamination procedures. The burnt wood is consistent with 17th-century hospital protocols that promote the burning and disposal of furniture, bedding, tableware, and other items that had come into contact with patients with infectious diseases, such as plague.

What appears to be the intentional sealing of the cistern with clay also supports this interpretation: Whoever dumped the items desired absolute containment.

This discovery suggests that more attention ought to be given to how our forebears dealt with disease containment, particularly in big urban centers such as Rome.

"Prior to the present study, the early modern disposal of waste from hospital and medical contexts in order to prevent the spread of disease had received only sporadic archaeological attention, with limited cross-contextual investigation," the researchers write.

"In consequence, the evidence put forward here adds significantly to our understanding of waste disposal practices in the Renaissance, while highlighting the need for a more complete overview of the hygiene and disease control regimes of early modern Europe."

The research was published in Antiquity.