Human noses come in a variety of shapes and sizes, from cute and petite to classically aquiline, broad and stately, bold and noble.

A new study by an international team of researchers has found at least some of the genes responsible for our nasal anatomy may have been inherited from our Neanderthal cousins.

The analysis covered individuals of mixed European, Native American, and African descent, matching regions of the human genome to the facial structures of certain individuals. These matches were then compared to other human and Neanderthal genome studies.

Altogether, researchers found 26 genetic regions that were strongly linked to a human's face shape.

Those with Native American ancestry tended to possess a gene inherited from Neanderthals called ATF3. Though mainly known for its role in nervous tissue

regeneration, the gene's expression is regulated by another gene that can affect the shape of the face.

Coupled with evidence that also suggests ATF3 becomes active as our faces are formed, the researchers suggest its presence just might make a significant difference in the growth of the nose.

In those of European descent, however, researchers found ATF3 was "essentially absent."

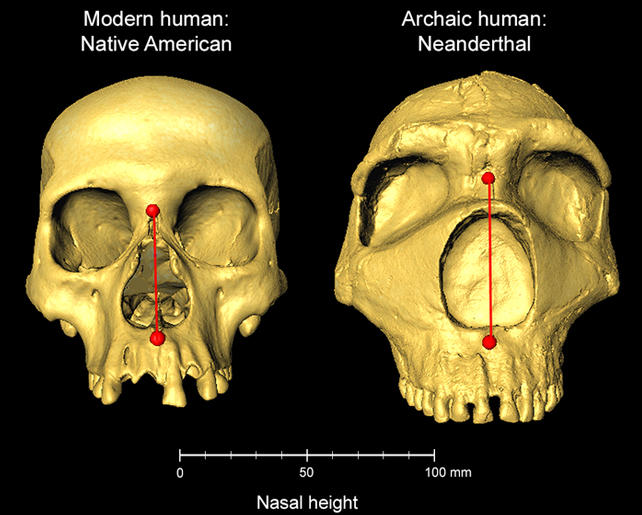

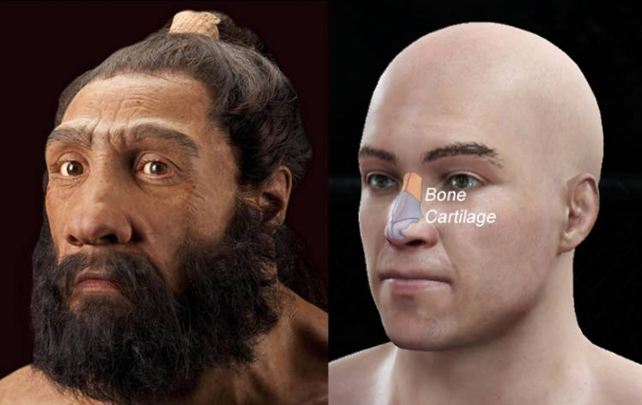

Previous studies on Neanderthal skulls have shown that their noses tended to be taller than those of modern humans.

The development of the ATF3 gene could be responsible, for at least part of this change. Other genes that shape the human nose exist as well, and initial studies suggest some of them might also be inherited from Neanderthals or Denisovans.

Given the persistence of ATF3 through the generations in Latin America, scientists think this particular gene might offer a survival advantage in some environments.

For instance, previous studies suggest that the shape of human noses can evolve to better suit the surrounding climate, regulating the temperature and humidity of the air we breathe in.

"The gene we have identified here may have been inherited from Neanderthals to help humans adapt to colder climates as our ancestors moved out of Africa," suggests geneticist Qing Li from Fudan University.

For now, that's just speculation. After all, some genes can persist through the generations even without survival advantages. The current study also only drew correlations between genome regions and facial features, not direct lines of cause and effect.

Still, recent genome studies indicate Neanderthals and prehistoric humans regularly reproduced with one another in Europe and Asia.

"In the last 15 years, since the Neanderthal genome has been sequenced, we have been able to learn that our own ancestors apparently interbred with Neanderthals, leaving us with little bits of their DNA," says geneticist Kaustubh Adhikari from University College London (UCL).

Some of the shared genes from these interbreeding events still stick with us to this day, and a few are even linked to health benefits, like safer births, and improved resistance to viruses or skin and blood infections.

How these genes might actually confer such health benefits is poorly understood. But the fact that scientists can use these connections to further probe a gene's effect is extremely valuable for future clinical research.

"Most genetic studies of human diversity have investigated the genes of Europeans," says geneticist Andres Ruiz-Linares from UCL.

"[O]ur study's diverse sample of Latin American participants broadens the reach of genetic study findings, helping us to better understand the genetics of all humans."

The study was published in Communications Biology.