A person's behaviour and way of doing things can often give them away to those who know them best, and now research says it's not just our outward idiosyncrasies that can identify us – even our brain activity is unique.

Researchers at Yale University in the US have found that images of brain activity taken by functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) can be used as a kind of 'cognitive fingerprint' to identify particular individuals – and can even correlate to how intelligent we are.

"In most past studies, fMRI data have been used to draw contrasts between, say, patients and healthy controls," said Emily Finn, co-first author of the study. "We have learned a lot from these sorts of studies, but they tend to obscure individual differences which may be important."

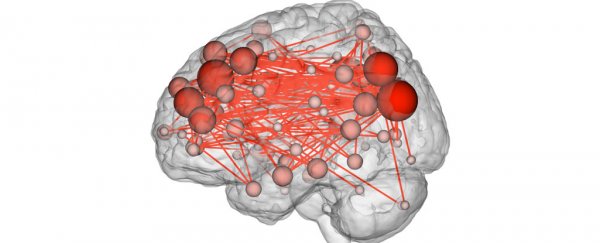

And those differences can be telling. So telling, in fact, that when the researchers analysed numerous fMRI scans taken of 126 participants sourced by the Human Connectome Project, they were able to identify individuals by recognising their unique 'connectivity profile'.

The researchers looked at activity across some 268 different regions in the brain by scanning the participants six times over. Sometimes the researchers engaged the participants with a cognitive task during the fMRI scan, while during other sessions, they simply rested during the procedure.

The researchers were able to identify individual participants with up to 99 percent accuracy when comparing scans of the same person involved in a similar cognitive task, although their strike rate fell to about 80 percent if the scan showed the same person doing a disparate task or being at rest.

"Until this, we really didn't know the extent to which each unique individual has a unique pattern of connectivity," Russell Poldrack, a cognitive neuroscientist at Stanford University and advisor to the Human Connectome Project, told Rachel Ehrenberg at Nature.

And beyond simply identifying who you are, the study also shows that brain activity can give researchers clues about a person's level of intelligence. While fMRI data doesn't simply indicate how smart you are, connectivity patterns in brain activity do correlate to how well people perform in an intelligence test, according to the researchers.

"[T]he uniqueness seems to be tied to cognitive function in some way," said Poldrack, with stronger connections in participants' prefrontal and parietal lobes correlating to better intelligence test scores.

While some might worry that these kinds of techniques could potentially be used for discriminatory purposes in the future – the prospect of having to undergo a mandatory brain scan as part of the interview process for a job or college position, for example – what excites the researchers is the potential for brain activity data to be used for therapeutic purposes, where treatments could be specifically tailored to an individual's unique brain connectivity profile.

"We have hundreds of drugs for treating neuropsychiatric illness, but there's still a lot of trial and error and failed treatments," Finn told Nature. "This might be another tool."

The findings are published in Nature Neuroscience.