Research suggests people can generate false memories within the blink of an eye.

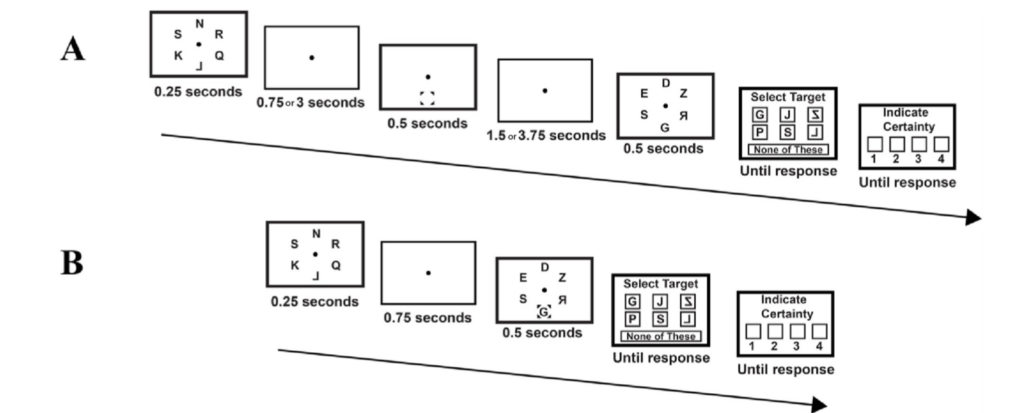

In a series of four experiments led by the University of Amsterdam, researchers showed 534 people letters of the Western alphabet in actual and mirrored orientations.

After some participants were shown an interference slide with random letters designed to scramble the original memory, all participants were asked to recall a target letter from the first slide.

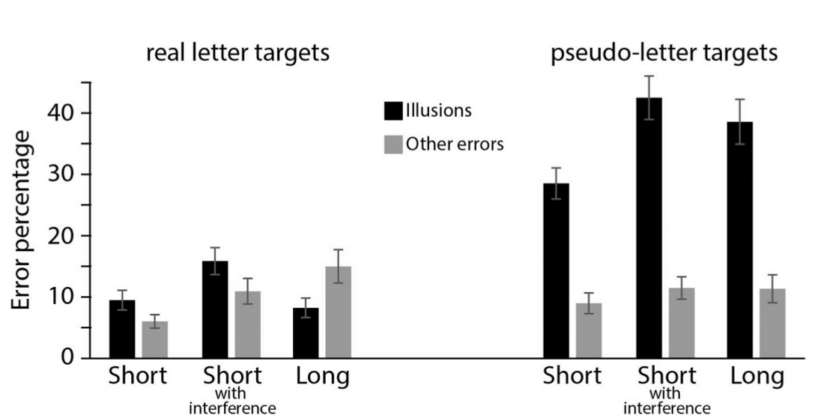

Half a second after viewing the first slide, almost 20 percent of people had formed an illusory memory of the target letter; this increased to 30 percent after 3 seconds.

The human brain alters memories according to what it expects to see. Because people included in the study were so familiar with the Western alphabet, their brains expected to see the letters in their actual orientation.

When letters appeared mirrored (Ɔ instead of C), people were more likely to remember the pseudo-letter as a real letter, even after only milliseconds had passed.

"It seems that short-term memory is not always an accurate representation of what was just perceived," the researchers write. "Instead, memory is shaped by what we expected to see, right from the formation of the first memory trace."

The researchers showed these were false memories rather than wrong guesses by asking the participants how confident they were in their memories on a score of one to four.

"Participants consistently report, with high confidence, that they have seen the real counterpart of a pseudo-letter target," the researchers write.

People were more likely to switch a pseudo-letter for a real letter than the other way around, suggesting that memory illusions are mediated by world knowledge of how things usually look.

The researchers differentiated these false memories from errors in initial perception by taking measurements at two time points. The only opportunity was during the 0.25 seconds in which the letters were flashed.

If perception errors were driving the mistakes, the error rate would be the same 500 milliseconds and 3 seconds later. When the error rate increased over time, this suggested that false memories were forming.

We know from experiments led by psychologist Elizabeth Loftus and others that false long-term memories can be easily generated.

For instance, adults can be persuaded to recall a vivid but fake memory of getting lost in a shopping center and crying as a child. In another study, people generated false, rich memories of committing crimes such as theft or assault.

Fake long-term memories are thought to be driven by the 'fuzzy trace theory', which states that memory comes from two parts: a verbatim part, which is what happened in real life, and a gist part, where the person interprets the meaning of the event based on semantic analysis.

A previous study showed that when people were given a picture of a face and a profession, they were more likely to link criminal labels such as 'drug dealer' to faces with Black features, indicating that internal biases were shaping memories.

In another study, people were given a list of three or four interrelated words (such as nap, doze, bed, and awake). When given a second list, participants were more likely to remember semantically related words not on the original list, such as sleep.

Fuzzy trace theory may also be driving short-term memory illusions but "cannot entirely explain the current findings", the researchers write.

These experiments suggest that our verbatim memory input is immediately integrated with previous experiences and expectations.

This paper was published in PLOS One.