Stomach acid isn't just useful for breaking down all the foods we eat – including some things we really shouldn't. It could also be harnessed to power tiny health devices that keep tabs on us from inside the body.

Scientists have developed a small ingestible voltaic cell that, when swallowed, operates inside the gastrointestinal tract, and generates energy when it comes into contact with acid in the gut.

The cell could be used to power sensors monitoring vital signs like heart rate or respiration, or as a battery for devices that provide medicines internally.

"We need to come up with ways to power these ingestible systems for a long time," says biomedical engineer Giovanni Traverso from MIT.

"We see the GI tract as providing a really unique opportunity to house new systems for drug delivery and sensing, and fundamental to these systems is how they are powered."

The voltaic cell recalls an experiment you might have tried in high school: the lemon battery, where citric acid carries a weak electric current between two electrodes.

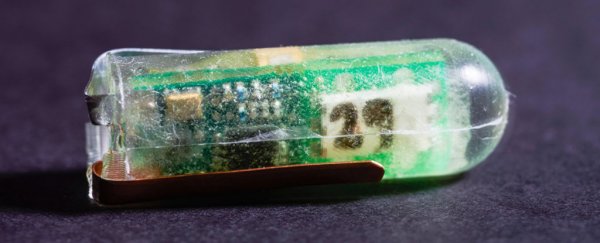

In the researchers' version of this, the ingestible is a relatively large cylindrical capsule, measuring about 40 millimetres long and 12 millimetres in diameter (1.6 inches by 0.5 inches), with zinc and copper electrodes attached to the surface of the device.

At that size, the prototype would be too large for human consumption. The researchers say it will be possible to scale the device down in the future to one-third its current size – so that people can swallow it – but at present the prototype has only been tested on pigs.

On the capsule, the zinc acts an anode, emitting ions when it comes into contact with gastric acid, which acts an an electrolyte, carrying an electric current to the copper cathode.

Testing the device in the stomachs of pigs, the cell generated a voltage of around 0.1 to 0.2 V, but the researchers were able to boost this using a capacitor inside the capsule to 2.2 to 3.3 V.

That's comparable to the voltage of a small alkaline battery, and was enough for the researchers to power a temperature sensor and a 900-megahertz wireless transmitter contained inside the capsule.

With the power produced by the cell, the sensor took readings of the temperature inside the pigs' stomachs, then transmitted the data to a base station 2 metres (6.6 feet) away, sending a new signal every 12 seconds.

"We can get relatively consistent power, enough to power temperature measurements on a minute by minute basis and transmit [them] wirelessly," one of the team, electrical engineer Phillip Nadeau told Abby Olena at The Scientist.

The size of the capsule depends on what kind of function you need the cell to power. The 40-mm-long capsule was large because it had to include temperature and wireless sensors.

But the team also developed a much smaller ingestible – about 2mm by 1mm by 1.5 mm (0.08 by 0.04 by 0.06 inches) – which could be used to release medication encapsulated by a gold film.

The benefit of these systems is that the ingestible power supply could be paired with all kinds of sensors or medical components – and unlike conventional batteries, free of potentially dangerous chemicals.

"Usually, if you have a battery inside the body, you have to package the battery with certain materials that are inert and seal the electrodes and the electrolyte inside," engineer Hanqing Jiang from Arizona State University, who wasn't involved with the research, explained to The Scientist.

With batteries like that, though, "you could potentially have leakage [of the] electrolyte into the human fluid, which is harmful or toxic", Jiang adds.

When ingested by the pigs, the device took about six days to travel through the digestive tract.

The high acidity of stomach juices provides the most power, whereas once the capsule moves through to the more neutral environment of the small intestine, the chemical reactions produce about a hundred times less voltage.

"But there's still power there, which you could harvest over a longer period of time and use to transmit less frequent packets of information," Traverso says in a press release.

As for when we'll see these ingestible batteries used in humans, that's still a while away, as there will need to be extensive research and testing done to make sure the devices are safe.

But the possibilities are truly massive, and could maybe even one day include sophisticated sensors and technologies that could help prevent diseases like cancer from developing.

"Stomach ulcers can become cancerous," researcher Sameer Sonkusale from Tufts University, who wasn't involved with the study, told The Scientist.

"[S]o if you put sensors in that can actually monitor how your gut lining is doing, then you might be able to prevent ulcers from becoming tumours and take preventive action."

The findings are reported in Nature Biomedical Engineering.