Our psychological profiles provide clues to our future risk and severity of cognitive decline that may one day inform tailored prevention strategies, a new study suggests.

"The aim was to elucidate how various combinations of psychological characteristics are related to mental, cognitive and brain health," explains University of Barcelona psychologist David Bartrés-Faz.

"To date, psychological risk and protective factors have been examined almost exclusively independently: this approach is limiting, as psychological characteristics do not exist in isolation."

Bartrés-Faz and colleagues surveyed more than 1,000 middle to older-aged adults and used the results to classify individuals into three psychological types based on comparable traits.

Profile 1 had low scores for what were considered 'protective factors', including self reflection, extraversion, agreeableness, openness, conscientiousness and a sense of purpose in life. Profile 2 was characterized with high negative risk traits, while Profile 3 had high protective and moderately low risk traits in comparison.

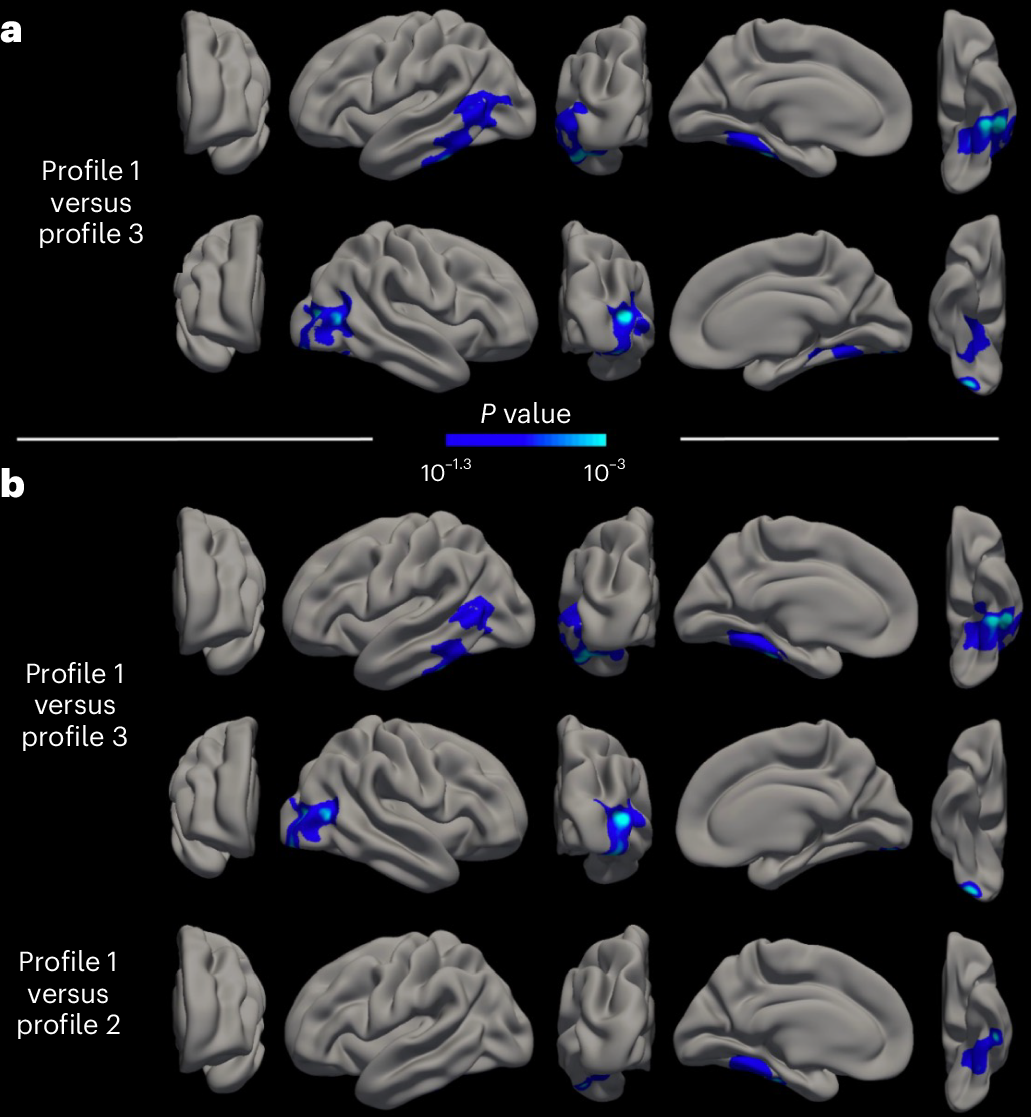

Over 500 of the participants had cognitive and MRI data taken at the start of the experiment and then again 2.3 years later during a follow up.

Those from Profile 1 had the lowest scores for protective factors, so lower levels of conscientiousness, openness to experience, extraversion and agreeableness. They performed most poorly in cognitive tests and had the highest measured brain atrophy during the follow up tests.

"Both clinicopathological and brain imaging studies have indicated that individuals with high purpose in life possess greater resilience to brain pathology regarding its impact on cognitive function," the researchers write in their paper.

Participants placed into Profile 2 maintained the highest levels of depression and anxiety in the initial and follow up stages of the study, and had the most memory issues and highest dementia risk scores early on.

But surprisingly they did not show notable differences in cognitive tests and cortical thickness compared to those in Profile 2 who had more balanced psychological characteristics during the follow up once anxiety and depression influences were factored out.

Further studies with larger sample sizes are needed to validate these findings, the researchers caution. The link between the Profile 2 psychological traits and cognitive decline are well established in past research.

Exactly why these relationships exist isn't clear. Distress arising from combinations of psychological characteristics may appear like a reasonable cause, though it's important to keep in mind psychological traits are often shaped by external stressors and experiences.

This is why poverty and/or trauma are also highly linked with cognitive decline, as they exacerbate risky psychological traits from the tendency to worry to full-blown anxiety.

Genetic influences of some traits could also play a role in reducing protection or increasing levels of risk.

All together though, the results highlight the need to evaluate both stresses and protective factors, the researchers recommend in their paper.

They suggest those in Profile 1 would mostly likely benefit from therapies that help them identify a sense of purpose, such as acceptance and commitment therapy, whereas group 2 profiles would likely respond better to distress reduction therapy.

Making sure people can access effective therapies could reduce the growing social and economic impacts of dementia in coming decades.

This research was published in Nature Mental Health.