The list of different factors that can affect cancer risk is a long one – from air pollution increasing it to drinking milk reducing it. Now a new study suggests that your chances of getting the disease are at least partly set before you're even born.

Led by a team from the Van Andel Institute in the United States, the researchers behind the study found that what happens during development in the womb can be linked to cancer risk – in both lowering and raising that risk, depending on the scenario.

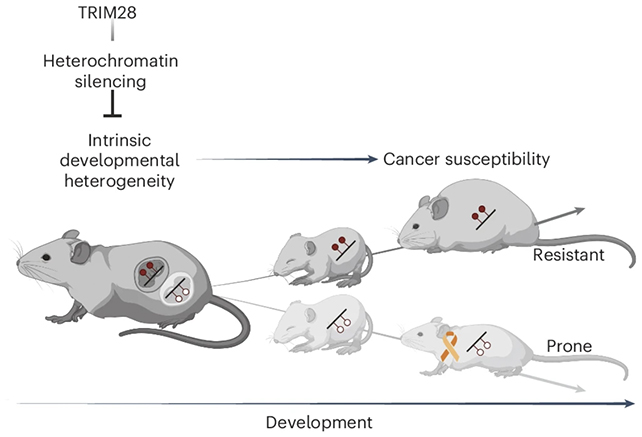

In particular, they identified two epigenetic states – patterns of gene programming – that affected cancer risk in genetically modified mice. The team focused on the protein TRIM28 in its role as an epigenetic controller: the way it turns genes on or off without altering the underlying DNA sequences.

The strengths of these gene patterns influenced whether cancer risk went up or down for the mice later in life. It's not clear what was causing the epigenetic variations in the mice, but it shows that even genetically identical mice can end up with varying levels of cancer risk, depending on their development.

"Our findings show that cancer's roots may start during the sensitive period of development, offering a new perspective to study the disease and potential new options for diagnosis and treatment," says Ilaria Panzeri, molecular biologist at the Van Andel Institute.

The team also found the type of cancer was different between groups. Cancers that developed in the lower-risk state were more likely to be liquid tumor cancers, like leukemia or lymphoma. In the higher-risk state, they were more likely to be solid tumor cancers like lung or prostate cancer.

How these two epigenetic states (or other states) might be developing isn't clear: it's possibly just random, but we've also seen previous studies link external prenatal factors (such as alcohol exposure in utero) to cancer risk.

"Because most cancers occur later in life and are understood as diseases of mutation, or genetics, there hasn't been a deep focus on how development might shape cancer risk," says J. Andrew Pospisilik, director of the Center for Epigenetics at the Van Andel Institute. "Our findings change that."

"Our identification of these two epigenetically different states open the door to an entirely new world of study into the underpinnings of cancer."

A better knowledge of those underpinnings can of course lead to new avenues to explore in terms of treatments – though this research is still in its earliest stages, with cancer cases continuing to rise sharply, it could prove vital in unlocking more of the disease's secrets.

"Everyone has some level of risk but, when cancer does arise, we tend to think of it just as bad luck," says Panzeri. "However, bad luck doesn't fully explain why some people develop cancer and others don't."

"Most importantly, bad luck cannot be targeted for treatment. Epigenetics, on the other hand, can be targeted."

The research has been published in Nature Cancer.