Those who take extreme risks often describe being drawn in by a feeling of compulsion.

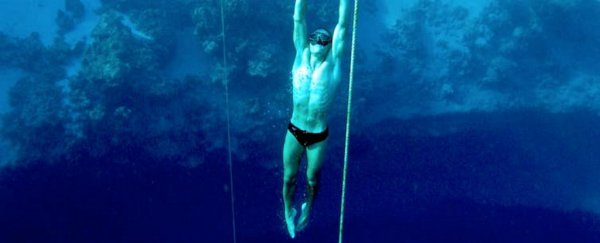

William Trubridge, a free-diving world record holder who regularly plunges his body hundreds of metres under water, simply explains "it beckons me beyond my means".

Most of us will be familiar with this feeling, even if we do not feel compelled to plummet headlong towards the ocean floor.

But we do not all experience the urge to take risks in the same way – or to the same extent. So why is that?

Researchers have long suspected that there may be genetic factors involved but that hasn't been confirmed until now. In our new study, published in Communications Biology, we have uncovered 26 genetic variants specifically linked to risk taking.

Our findings are important because, while the term "risk taker" might conjure images of an athletic individual who enjoys free diving and helmet-less mountain biking, the reality is less glamorous. Risk taking often manifests itself in day-to-day decisions which can result in poor health over time.

For example, risk prone individuals are more likely to be smokers and to have first tried smoking when they were young. They are also more likely to drink alcohol regularly and develop addictions. We wanted to examine the genetic determinants of risk taking to shed light on its biological mechanisms and their implications for health.

So, would you describe yourself as someone who takes risks? This was the question posed to 500,000 healthy adults from across the UK who enrolled in the UK Biobank study, which stores genetic data. Roughly one-quarter responded yes. On average, these individuals consumed more alcohol and were more likely to have tried smoking and report drug addictions than those who responded no – confirming that there might be important health implications involved with risk taking.

Surprising findings

Looking at their genomic data, our analysis revealed 26 variants in regions of the human genome (genetic loci) associated with a self-reported inclination toward risk taking. The genes located at these regions are richly expressed in the central nervous system and immune system.

That the brain plays a key role in risk-taking behaviour is hardly surprising. The four specific brain regions highlighted in our analysis – the pre-frontal cortex, hippocampus, anterior cingulate cortex and hypothalamus – have all been previously linked to personality traits relevant to risk taking. For example, the hippocampus regulates behavioural inhibition, the tendency to withdraw from the unfamiliar.

The association with the immune system was initially more surprising. But there is increasing evidence that the immune system is involved in mood and behavioural problems, such as depression. There is also research suggesting that immune function and personality are linked.

Next, we investigated how the genetics of risk taking relates to the genetics of other health-related traits. We found that risk taking shares a genetic basis with aspects of body composition, such as childhood obesity and waist-to-hip ratio. There are also genetic links between risk taking and lifestyle decisions – such as having your first child early (for women) and having tried smoking. Additionally, we found that the genetic variants that make you risk-prone also make you more likely to develop psychiatric illnesses, such as bipolar disorder and schizophrenia.

Emotional eating and BMI

In addition, four of the 26 genetic loci implicated in risk taking are associated with body mass index (BMI), the measure commonly used to indicate if a person is overweight or obese. Our discovery of genetic links between risk taking and BMI is intriguing. Other (non-genetic) research suggests that overweight and obese individuals are more risk prone than their healthy weight counterparts. For example, extremely obese adolescents are more likely to have tried smoking than their peers.

Some studies go further and suggest that being risk-prone might actually contribute to causing obesity, hypothesising that impulsive food choices, poor meal planning or binge eating provide plausible mechanisms.

Our research provides partial support for the idea that behaviour surrounding food links risk taking to obesity. We found that the more risk increasing gene variants an individual carries, the more calories, fat and protein they tend to consume daily. These people are also more likely to skip breakfast and, if they are male, to eat in response to unpleasant emotions. Both of these food-related behaviours are linked to weight gain.

However, our results indicate that this is not the whole story. While skipping breakfast and emotional eating are both associated with weigh gain, the finding of an overall association between genetic variants involved in increased risk taking and these behaviours masks a wide variation in the effects of individual variants. In fact, some of which are actually associated with lower BMI. Our evidence suggests that, while risk taking and BMI are linked, it is unlikely that all broadly defined risk takers are directly vulnerable to obesity – there are several pathways involved.

This conclusion is perhaps unsurprising given the wide range of behaviours that might be described as "risk-taking" – from extreme sports to risky investment decisions and unhealthy eating. Further investigation of risk taking and of the 26 genetic loci that we uncovered will deepen our understanding of specific facets of risk-taking propensity and behaviour that contribute to obesity risk. We expect that larger studies will uncover many more genes that contribute to risk taking in the future.

![]() Risk taking has a mixed reputation. On one hand, it is celebrated for its links to human discovery and endeavour. Astronaut Neil Armstrong famously proposed that "there can be no great accomplishment without risk". On the other hand, we are wary of risk. Cultures that emphasise, and perhaps exaggerate, the control we have over our lives regard risk with a strong degree of caution. It is fitting, then, that our exploration of the genetic underpinnings of risk taking has added intrigue to our understanding of its links with health and well being.

Risk taking has a mixed reputation. On one hand, it is celebrated for its links to human discovery and endeavour. Astronaut Neil Armstrong famously proposed that "there can be no great accomplishment without risk". On the other hand, we are wary of risk. Cultures that emphasise, and perhaps exaggerate, the control we have over our lives regard risk with a strong degree of caution. It is fitting, then, that our exploration of the genetic underpinnings of risk taking has added intrigue to our understanding of its links with health and well being.

Emma Clifton, PhD student, University of Cambridge; Felix Day, , University of Cambridge, and Ken Ong, Group Leader of the Development Programme at the MRC Epidemiology Unit, University of Cambridge.

This article was originally published by The Conversation. Read the original article.