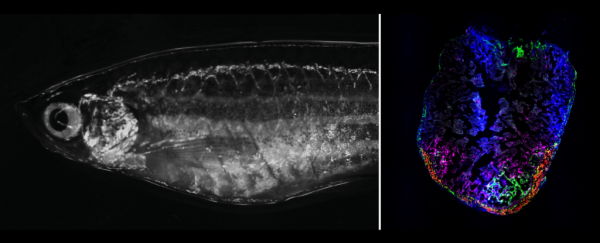

Zebrafish are marvelous creatures. Not only are they completely see-through, but they can also grow new organs. We already knew these translucent little fish could regenerate retinal tissue in their eyes – now new research shows how zebrafish can revive heart tissue after injury.

"We wanted to find out how this little fish does that, and if we could learn from it," says developmental biologist and study author Jan Philipp Junker of the Berlin Institute for Medical Systems Biology in Germany.

Published in Nature Genetics, the new study led by Junker along with Daniela Panáková, a cell signaling researcher at the Max Delbrück Center for Molecular Medicine, chronicles the cascade of events leading to heart regeneration in zebrafish.

In humans, cardiac muscle cells called cardiomyocytes cannot regenerate like the zebrafish heart cells do. Starved of oxygen during the grips of a heart attack, our cardiomyocytes become damaged, and permanent scarring (called fibrosis) forms in place of lost muscle, leaving the heart weaker than it was before.

Zebrafish, however, are capable of regrowing up to 20 percent of their one-millimeter-sized hearts within two months of a heart injury.

What this new study shows us is that connective tissue cells called fibroblasts are the conductors of that heart regeneration process in zebrafish, producing proteins that act as repair signals.

Excitingly, the new findings come hot on the coattails of other promising efforts in regenerative medicine – that look to either replace or repair damaged hearts with cell-based therapies or drugs that mimic molecules found in zebrafish.

Earlier this year, surgeons implanted a pig heart into a human patient for the first time (though, sadly, the man died two months later).

In May, researchers also pinpointed the human cells that help the human heart patch itself up after a heart attack.

And in June, scientists succeeded in 'healing' a heart attack in mice with an mRNA technique that delivers genetic instructions to heart muscle cells to repair themselves.

In this new study, the researchers zapped the animals' teeny hearts with an ultra-cold needle to mimic a human heart attack (also called a myocardial infarction) and watched what happened.

"Surprisingly, the immediate response to the injury is very similar," says Junker. "But while the process in humans stops at that point, it carries on in the fish. They form new cardiomyocytes, which are capable of contracting."

Using single-cell sequencing techniques, the team then scanned around 200,000 heart cells isolated from zebrafish before and after injury, extracting genomic information from individual cells to see which ones were active in a damaged heart.

They discovered three types of fibroblasts temporarily entered an activated state, switching on genes that encode muscle-building proteins such as collagen XII, which promotes connective tissue growth.

And when the researchers 'silenced' those genes in the zebrafish, their hearts could no longer regenerate.

"They form right at the site of injury, after all," Junker says of the collagen-expressing fibroblasts.

While fibroblasts might play a key role, past research with zebrafish has shown that inflammatory cells called macrophages are swift responders to heart attacks and required for heart regeneration.

The epicardium, the outer layer of the heart, has also been identified as a hub for heart regeneration, something which this new study supports.

After engineering cells with unique genetic 'barcodes', the researchers traced the activated fibroblasts and showed they were made in the zebrafish epicardium, and only there did the cells produce collagen XII.

Single-cell sequencing techniques, the likes of which the researchers used in this study to locate heart cells sending out regenerative signals, are at the forefront of fast-advancing genomic technologies.

Although single-cell sequencing is widely used and provides exceptional detail about the activity of single cells, more research to validate the study findings in other model organisms will be needed. It's unclear if the same fibroblast-led mechanisms are also found in mammals such as humans and mice.

"Heart regeneration is a complex process that's influenced by many different things," says study author and developmental biologist Bastiaan Spanjaard, also of the Berlin Institute for Medical Systems Biology.

"The experiments produced enormous quantities of data. Filtering the correct biological signals out of them was hugely challenging."

The team also wants to look more closely at the genes which are switched on in activated fibroblasts, encoding proteins that – at least in zebrafish – appear to stimulate heart muscle cells to regrow.

For now, the study sheds more light on the biological processes happening in response to a heart attack, insights that might, in time, help stave off subsequent cardiac events that become more risky after the first attack.

The study was published in Nature Genetics.