A new paper provides a stark reminder that the virus responsible for COVID-19 is still spreading, with 9 animals out of 47 testing positive for SARS-CoV-2 at a zoo in Brazil.

It's likely that the animals caught the virus from humans.

"Zoos are unique in terms of the epidemiology of human-animal interactions," the team led by researchers from the Federal University of Minas Gerais in Brazil writes in their paper.

"They shelter multiple species of wildlife from a wide range of taxonomic groups in relative proximity, and interactions between animals and humans are frequent, especially for animal caregivers."

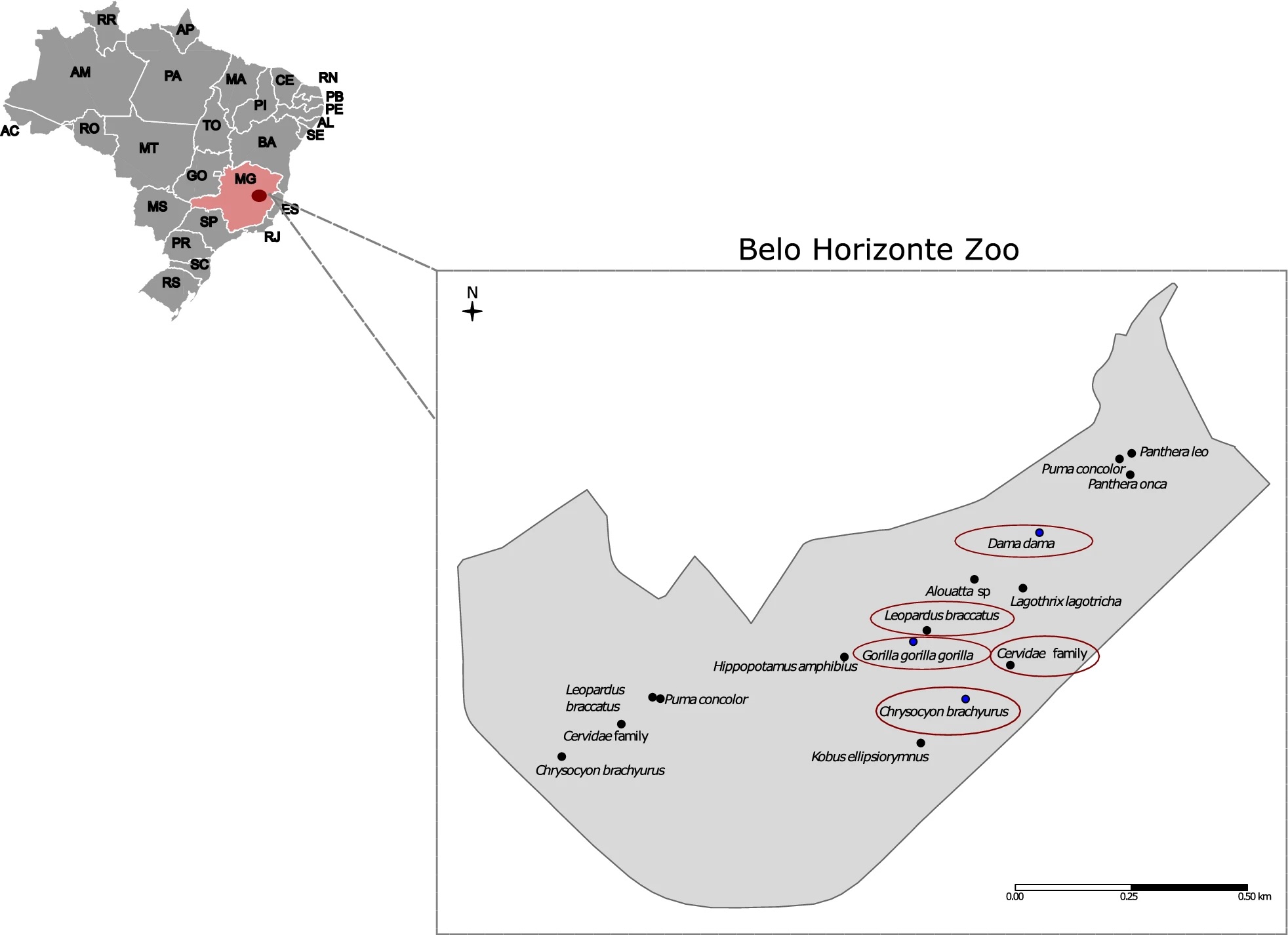

Testing for the virus was conducted at the Belo Horizonte Zoo between November 2021 and March 2023. The researchers were able to sequence three of the viral genomes found in the nine animals.

A maned wolf (Chrysocyon brachyurus) and a fallow deer (Dama dama) were found to be harboring the infamous Alpha variant, and a western lowland gorilla (Gorilla gorilla gorilla) had the Omicron strain.

The SARS-CoV-2 RNA collected from the animals clustered close to human samples from the same region.

"Close contact between zoo animals and their caretakers is a likely route of infection," the authors note.

This certainly applies to infections in the November 2021–January 2022 period, but more animals became infected after the zoo reopened to the public in February 2022, which may be due to increased infections between the public and the keepers, and subsequently the animals.

Interestingly, a map of the zoo shows the infected species are somewhat close neighbors in the overall layout.

Of the animals that tested positive at the zoo, there were three western lowland gorillas and two maned wolves in total, as well as a pampas cat (Leopardus braccatus), a brown brocket deer (Subulo gouazoubira), a red deer (Cervus elaphus), and one fallow deer.

Since SARS-CoV-2 was discovered in December 2019, scientists have been concerned about its ability to jump between species, especially from humans to previously uninfected animal species.

Not only does this potentially threaten newly infected species, but it also offers the virus a chance to form natural reservoirs from which to evolve and spark future outbreaks.

Disease control in zoo animals is imperative, in part because of the animals' contact with humans and their close quarters with other animals, but also because many are involved in important conservation programs aimed at helping to save their species.

For instance, western lowland gorillas are critically endangered, and the World Organization for Animal Health records show they are highly susceptible to SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Early detection of infections in zoo animals could help researchers better understand how to prevent the virus from spreading and evolving in – or worse, decimating – wild populations.

"The detection of different variants suggests ongoing viral evolution and adaptation in new hosts," the authors write.

"These findings underscore the need for integrated public health strategies that include wildlife monitoring to mitigate the risks posed by emerging infectious diseases."

This research was published in Virology Journal.