Once upon a time, 99 million years ago, some tiny frogs in what is now Myanmar ended up having a pretty bad day - trapped in a golden sticky mess of tree sap. Over the years, that sap hardened, and today those frogs are the oldest we've ever found preserved in amber.

The four fossils from the amber deposits in southeast Asia are also the earliest direct evidence of frogs living in wet tropical forests.

Previous frogs preserved in amber date back to 40 million years ago in the Caribbean and 25 million years ago in Mexico.

"It's almost unheard of to get a fossil frog from this time period that is small, has preservation of small bones and is mostly three-dimensional. This is pretty special," said herpetologist David Blackburn of the Florida Museum of Natural History.

"But what's most exciting about this animal is its context. These frogs were part of a tropical ecosystem that, in some ways, might not have been that different to what we find today - minus the dinosaurs."

Frogs are small and fragile, so their fossils don't tend to survive particularly well, especially not from damp rainforests where they'd quickly decompose. The oldest true frog fossil ever found is about 190 million years old, and most of the fossil record tends to consist of larger species, from dry environments.

But most of today's frogs live in wetter environments, so it's likely that they inhabited similar surroundings in the past, too.

"Ask any kid what lives in a rainforest, and frogs are on the list," Blackburn said. "But surprisingly, we have almost nothing from the fossil record to say that's a longstanding association."

(Lida Xing/Florida Museum)

(Lida Xing/Florida Museum)

But you know what else lives in rainforests? Trees. Dripping their sticky sap all over everything, encasing it, and then petrifying, providing an invaluable snapshot of the forests as they were.

And the Myanmar amber deposits are particularly rich, giving us strange arachnids, birds, a chameleon, a "vampire" ant, and even the tail of a small dinosaur, bristling with feathers.

Now they've ponied up four frogs, the best preserved of which is a newly discovered (but extinct) species the researchers named Electrorana limoae.

(Lida Xing/Florida Museum)

(Lida Xing/Florida Museum)

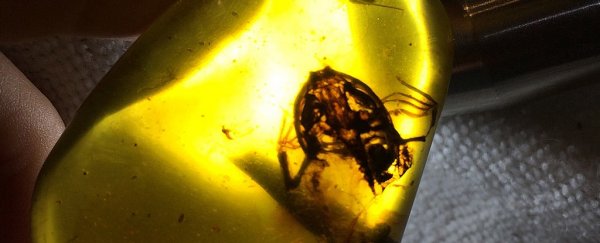

The piece of amber contains the frog's head, forelimbs, part of its spine, and part of one of its hindlimbs, as well as an unidentified beetle. The specimen is less than an inch in length, and was not yet fully grown.

Because it's so young, and only partial, many of the skeletal characteristics herpetologists use to determine how a frog is related to other frogs are either not yet fully formed, or missing. These include the wrist bones, the pelvis and hip bones, the inner ear, and the top of the spine.

The existing bones hint that Electroana could be related to fire-bellied toads and midwife toads, but there's a problem - those Eurasian species live in temperate climates, not wet rainforests.

(Lida Xing/Florida Museum)

(Lida Xing/Florida Museum)

And the other three fossils are little help - they contain just two hands, and the imprint of a frog that probably decomposed inside the resin. But a growing database of CT scans of the skeletons of current frogs might help, as could future fossil discoveries.

"We don't have a lot of single-species frog communities in forests. It seems extremely unlikely that there's only one. There could be a lot more fossils coming," Blackburn said.

And that would be amazing.

The fossils are at the Dexu Institute of Paleontology in Chaozhou, China, and there's a 3D-printed replica of Electrorana limoae at the Florida Museum. You can also interact with 3D models of the fossils on Morphosource.

The paper describing the fossils has been published in Nature Scientific Reports.