Scientists have drawn attention to the fact that lab mice living in super-clean conditions might be confusing the results of immune system studies.

In humans, our immune systems are tuned throughout life with exposure to various pathogens. We use that to our advantage by creating vaccines, and investigate the microbiome to find out more about how microorganisms are influencing our health.

Mouse immune systems are also influenced by their microbiomes, and a pair of researchers from University of Texas Southwestern Medical Centre are drawing attention to this important fact.

"Experimentation in mice has promoted an explosion of knowledge in immunology and other biomedical fields," write immunologists Tiffany Reese and Lili Tao.

"Despite the significant advances we have made in understanding the immune system from mouse studies, there is increasing concern over the utility of mouse models."

This concern comes from the fact that lab mice are usually bred in extremely clean conditions, keeping them clear of any infections whatsoever. This is known as 'specific pathogen-free' (SPF) approach.

An SPF-bred mouse is bound to have a different microbiome from its naturally bred counterparts, and that could mess up the results of an immune system study, the researchers explain.

If we're then drawing conclusions from that mouse study to apply to humans, we can run into huge discrepancies, because humans don't grow up in sterile conditions.

The researchers combed recent scientific literature to assess whether the SPF approach is indeed changing the immune systems of science mice. They found several such cases involving viruses, bacteria, and parasites.

For example, if lab mice are protected from murine cytomegalovirus (a common affliction in wild mice), their immune responses significantly change to the point where the rodents are able to survive otherwise lethal bacteria.

"These pathogens likely represent components of the mouse microbiome, and may influence many aspects of mouse physiology in important ways," the team explains.

The researchers emphasise that the literature review gives a perspective on current research models involving mice, and is not a call for stopping SPF breeding. But they do suggest that we need to expose lab mice to a wider range of germs.

"Cohousing mice with pet store mice is one option," they write, adding that this could cause problems for reproducing results, since batches of lab mice cavorting with pet store mice would inevitably end up having different bugs in their system.

The condition of lab animals is regularly addressed in research, as scientists work to devise alternatives for animal models, and assess whether current approaches are the best we can do.

A recent study funded by UK's National Centre for the Replacement, Refinement & Reduction of Animals in Research has advised scientists that even the way you pick a mouse up can influence the results of a behavioural test.

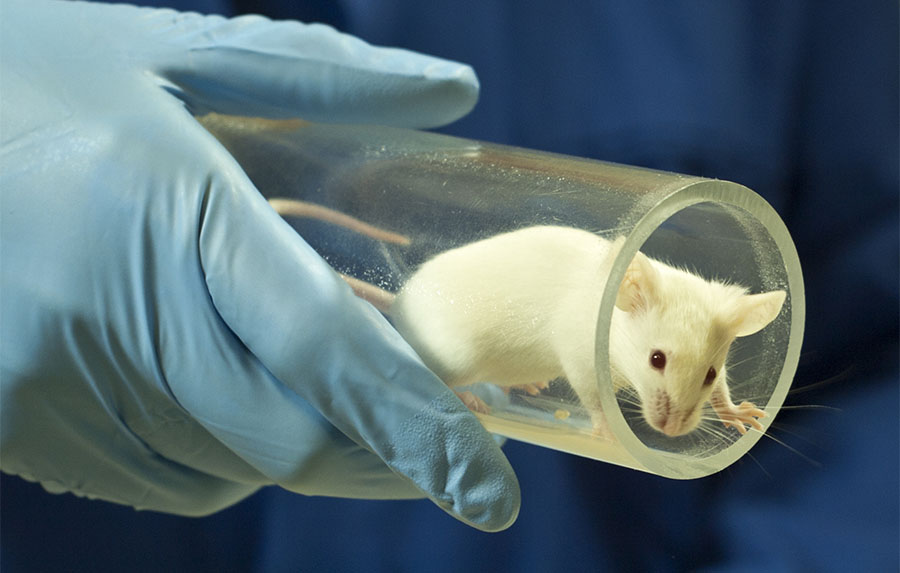

According to lead researcher Jane Hurst from the University of Liverpool, the best way to eliminate stress in a lab mouse is to pick it up using a clear acrylic 'handling tunnel', which is less scary than being picked up by the tail (a typical approach) or even gently cupped on an open palm.

Jane Hurst, University of Liverpool

Jane Hurst, University of Liverpool

Hurst has previously shown that the handling tunnels eliminate anxiety in mice, and the new research shows that mice picked up by the tail are less inclined to explore a new environment and this affects their performance in tests.

For now, it's not possible to entirely avoid using animals in the lab, but at least we know that scientists are working to ensure that every mouse counts.

The mouse germ study was published in Trends in Immunology. The handling study was published in Scientific Reports.