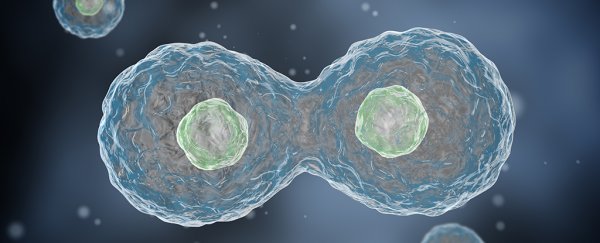

Throughout our lifetimes, our cells divide to create new cells to keep the body running, ensuring a steady supply of biological building blocks. This process not only protects against illness, it could also help fight cancer cells, according to new research.

The latest study uses mass spectrometry to analyse the way this DNA replication is regulated to keep it running smoothly – scientists have been able to precisely map the flow of nucleotides, the basic units of DNA and RNA.

And the team from the University of Copenhagen in Denmark says that by tweaking the chemical signalling that's going on inside these cells, we could potentially cause cancer cells to crash and burn by replicating too quickly without any brakes.

"We can see that these processes follow the same periodic rhythm," says one of the researchers, Jiri Lukas.

"We found a mechanism that instantly slows down DNA-replication when RNR, the nucleotide factory, gets out of that rhythm, but well before the nucleotide supply becomes critically low."

In other words, when the ribonucleotide reductase (RNR) enzyme isn't producing enough nucleotide units, a message gets passed up the chain to slow down DNA replication too.

That's vital as cells divide – if the DNA information isn't exactly the same in both of the newly split cells, then our genetic code gets scrambled, which can lead to numerous diseases in the body.

A protein called PRDX2 was identified by the researchers as the chemical messenger involved, slowing down cell (and DNA) copying when there's a bottleneck further up the chain. Eventually, nucleotide production can catch up again.

The end result is there are always enough nucleotides to ensure the DNA gets accurately copied. The overall process is well-known, but this is the first study to really examine how nucleotide production and cell division regulate their speed.

So how does all this apply to cancer? Well, cancer cells don't happen to like speedy division and replication, and if we can switch off the chemical signalling that warns them about nucleotide slowdowns, they might produce enough errors to kill themselves off.

"We found that cancer cells copy their DNA rather slowly, because they have abnormal genomes and replicating DNA has to overcome many obstacles," explains one of the team, Kumar Somyajit.

"When we remove their ability to copy their genomes slowly, the cancer cells die because they cannot cope with too many bumps on their DNA templates."

It's almost like putting the cancer cell production line into overdrive – at that speed the cancer cells, which are more complex than normal, can't properly spread themselves.

Any kind of treatment based on these findings is still a long way off, but we now understand more about this most crucial of biological functions - and that's going to help us both prevent disease and treat disease in the future.

The good news is it's not the only line of attack we've got. A new type of cancer immunotherapy, where a person's own cells are used to attack the disease, was approved by the FDA earlier this year.

Meanwhile, in September researchers working in the UK announced they had developed a new type of cancer cell suicide mechanism. It works in the lab, and the challenge now is to see if the same effects can be reproduced in humans.

All of which gives us hope that better and more effective cancer treatments are well on their way.

The research has been published in Science.