The scientists liken it to 'singing', but to our ears the creepy dirge of Antarctic ice shelf vibrations sounds more like the sinister score of a horror movie.

Researchers on Antarctica's Ross Ice Shelf have recorded the slow seismic hum generated by wind forces whipping across the ice sheet's frozen landscape.

The frequency detected is far too low for the human ear to hear naturally, but when it's sped up some 1,200 times, what emerges is an eerie soundtrack of restlessness hidden within the bleak polar isolation.

"It's kind of like you're blowing a flute, constantly, on the ice shelf," says geophysicist and mathematician Julien Chaput from Colorado State University.

Once it's rendered audible, here's what the creepy vibration phenomenon sounds like:

Of course, Chaput and his team weren't originally setting out to make the soundtrack to a horror movie.

The purpose of their research was to learn more about the physical properties of the Ross Ice Shelf, Antarctica's (and the world's) largest floating slab of ice, which is roughly the size of Spain.

As the world keeps getting catastrophically hotter, Antarctic ice shelves are beginning to dramatically collapse and break apart.

To better understand the forces at work, Chaput and fellow researchers buried 34 seismic sensors under the deep snow layer that sits atop the Ross Ice Shelf's underlying ice.

These seismic sensors monitored the ice shelf's structure from late 2014 to early 2017, and when the team analysed the data, they realised this snowy cover – known as the firn layer, which insulates the ice below – undergoes constant movement from exposure to the wind above.

"We discovered that the shelf nearly continuously sings at frequencies of five or more cycles per second," the authors explain, "excited by local and regional winds blowing across its snow dune‐like topography."

According to the researchers, variations in wind strength (due to things like storms) and changes in air temperatures can both impact the snow layer, and in so doing affect the pitch of the seismic hum detected.

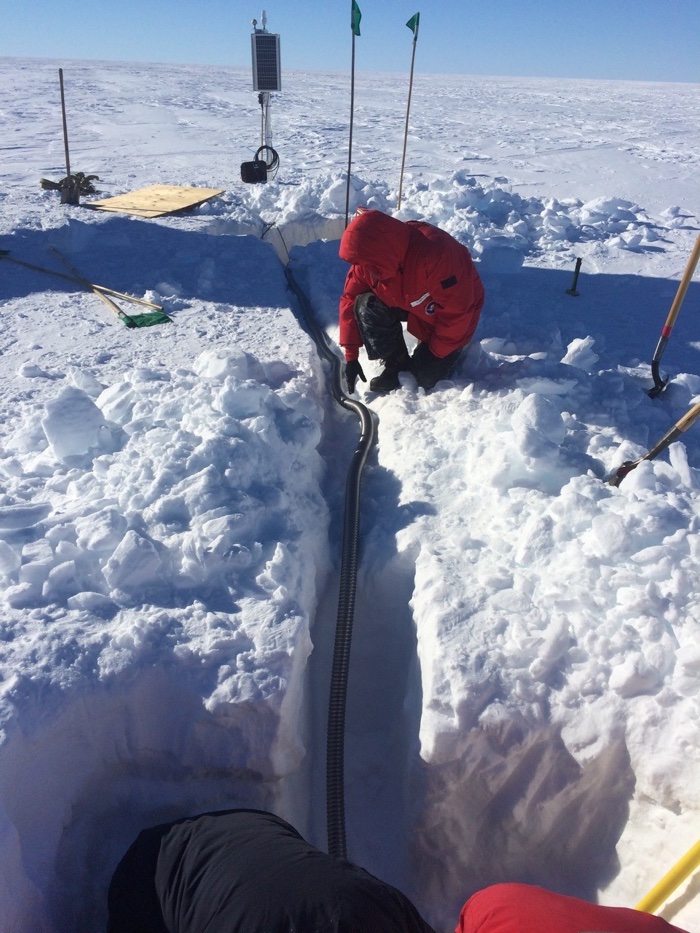

Laying conduit to power the seisometers (Rick Aster)

Laying conduit to power the seisometers (Rick Aster)

"Either you change the velocity of the snow by heating or cooling it, or you change where you blow on the flute, by adding or destroying dunes," Chaput explains.

"And that's essentially the two forcing effects we can observe."

Studying how these vibrations behave and evolve over time could help us learn more about how ice sheets are responding to a world that's getting too hot too fast, researchers think.

"Like the thick, hairy hide of the woolly mammoth, the upper skin of the Antarctic ice sheet … is the most important protection from the ravages of a warming climate," writes glaciologist Douglas MacAyeal, who wasn't involved with the study, but has authored a commentary on it.

"What should concern geoscientists most about Antarctica's protective skin of firn is whether, and how, it will be breached by surface melting and meltwater percolation processes in the coming century."

That's a point Chaput agrees with.

"Melting of the firn is broadly considered one of the most important factors in the destabilisation of an ice shelf," he told Gizmodo, "which then accelerates the streaming of ice into the ocean from abutting ice sheets."

It's a crucial time for this kind of research, as the ice in polar regions undergoes massive shifts glaciologists are struggling to keep track of.

Thanks to Chaput and team, we've now got another means of keeping tabs on these monumental transformations taking place – even if the overall picture is looking grimmer than ever.

Basically, another song nobody wants to hear.

The findings are reported in Geophysical Research Letters.