For decades the existence of weird space clouds in Earth's orbit has been speculative and controversial, but new research looks to validate their strange reality after all.

The Kordylewski clouds – two mysterious swarms of dust trapped between the competing gravitational fields of Earth and the Moon – were first hypothesised back in the 1950s, although evidence for their existence was faint.

Now, a new study by researchers at Eötvös Loránd University in Hungary helps make the case for these unusual, ever-present satellites in the sky.

"The Kordylewski clouds are two of the toughest objects to find, and though they are as close to Earth as the Moon, [they] are largely overlooked by researchers in astronomy," says first author of the study, astronomer Judit Slíz-Balogh.

"It is intriguing to confirm that our planet has dusty pseudo-satellites in orbit alongside our lunar neighbour."

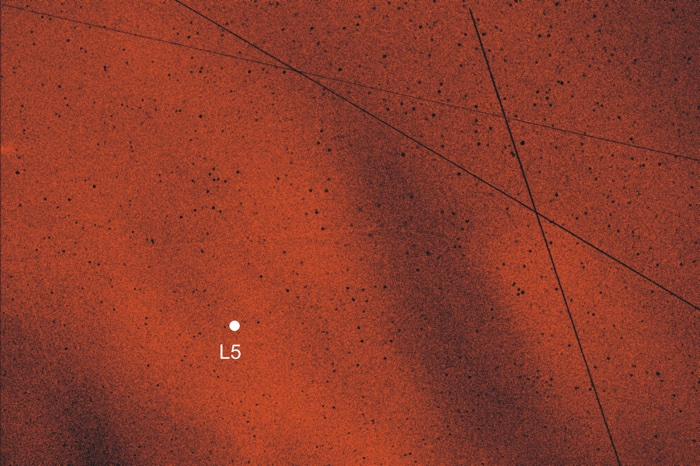

The L5 point, with central region of the Kordylewski cloud visible in bright red pixels (J. Slíz-Balogh)

The L5 point, with central region of the Kordylewski cloud visible in bright red pixels (J. Slíz-Balogh)

The Kordylewski clouds have been speculated about for decades, but the science that underpins their existence goes back even longer.

In space, the Kordylewski clouds occupy positions that are called Lagrange points – locations where small objects get stuck in a gravitational nexus between the forces exerted by two larger bodies.

Lagrange points were first discovered in the 18th century, and there are five of these co-orbital points in any applicable system, such as the Sun-Earth system, the Earth-Moon system, and many others.

In the case of the Earth-Moon system, two of these five points – L4 and L5, sometimes called trojan points – form an equal-sided triangle with Earth and the Moon.

Theoretically, interplanetary particles could be trapped inside these points forever, were it not for the gravitational perturbation of even greater bodies (such as the Sun, in this instance) or other destabilising forces (like solar wind) eventually coaxing them out into the open.

In 1961, Polish astronomer Kazimierz Kordylewski became the first scientist to claim photographic evidence of this dust accumulation phenomenon, although the extreme faintness of dust almost 400,000 kilometres (about 250,000 miles) away makes such observations difficult to confirm.

Artist's impression of Kordylewski cloud in the night sky (G. Horváth)

Artist's impression of Kordylewski cloud in the night sky (G. Horváth)

Nonetheless, that's what Slíz-Balogh's team set out to do in their new research.

In the first paper of a two-part study, the researchers modelled how Kordylewski clouds (KDC) might form, with almost 2 million particle simulations confirming that swathes of interplanetary dust would become trapped at L5, if only temporarily, before making an escape days later, depending on orbital configurations.

"According to our computer simulations, the KDC has a continuously changing, pulsing, and whirling shape, furthermore, the probability of dust particles being trapped is random due to the occasional incoming of particles and their incidental velocity vectors," they write.

"Therefore, the structure and particle density of the KDC is not constant."

In the second part of their research, the researchers attempted to photograph the phenomenon themselves.

After several months of perseverance – waiting for a sufficiently cloudless and moonless night in Hungary – the team captured evidence of the Kordylewski cloud at L5, using a technique called sequential imaging polarimetry to detect the extreme faintness of the particles.

"Since this dust cloud is illuminated by direct sunlight, the faint light scattered from the dust particles can be observed and photographed from the Earth surface with appropriately radiance-sensitive detectors," the authors explain.

"We conclude that for the first time we have observed and registered polarimetrically the KDC around the Lagrange point L5 of the Earth and Moon."

As for now, photographic evidence of the same accumulation taking place at L4 is something that still has to be regarded as hypothetical, but the new research makes a strong case that Kordylewski got it right almost 60 years ago.

In the longer term, there's a lot more than just interplanetary particles swirling around here.

In the same way that natural orbital satellites congregate at L4 and L5 points, there's a history of spacecraft exploiting the same phenomena, using Lagrange points as stable zones for things like probes and space telescopes.

Pretty handy parking spots to know about, if you don't mind a bit of dust.

The findings are reported in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society here and here.