We all know that there's no air to breathe on the Moon, but new evidence suggests that the lunar surface is continually being showered by oxygen escaping Earth – and may have been for billions of years, since Earth's atmosphere developed.

Scientists have discovered that oxygen ions from Earth's atmosphere are transported to the Moon once a month, during a five-day window when the lunar satellite passes through our planet's protective magnetosphere. In this time, the Moon passes behind Earth, getting a short reprieve from the blast of the Sun's solar wind – and is sprinkled with a stream of material fleeing Earth instead.

While scientists had already suggested that traces of gases such as nitrogen could have ended up on the lunar surface after escaping our atmosphere, this is the first time researchers have shown that oxygen – one of the most important components of life on Earth – is also shipped direct to the Moon.

"Our new finding suggests that the Earth-Moon system coevolves not only physically but also chemically," astrophysicist Kentaro Terada from Osaka University in Japan told EOS.

The findings could explain a longstanding mystery about the chemical composition of rocks on the Moon.

Since the Moon doesn't have a protective magnetic field like Earth, it gets near-constantly buffeted by the solar wind – a stream of highly charged particles emanating from the Sun.

Because of this, it was thought that lunar sediment taken from the exposed surface of the Moon would provide a chemical match for the material that makes up the solar wind.

But when scientists analysed lunar rocks back in 2006, they found the oxygen levels didn't match up, which could have meant that something else was messing with the oxygen composition in the lunar soil.

Now, Terada's team has an explanation for what that contamination could be.

Analysing data from Japan's SELENE lunar orbiter (aka Kaguya), they found that the spacecraft recorded high levels of oxygen ions – positively charged oxygen molecules – while it was orbiting the Moon between 2007 and 2009.

The thing is, these oxygen ions weren't constant. SELENE only detected the chemical during a distinct five-day period during each lunar orbit – which takes approximately 27 days.

That short window happened to coincide with when the spacecraft and the Moon were shielded from the solar wind by Earth's magnetosphere.

Osaka University/NASA

Osaka University/NASA

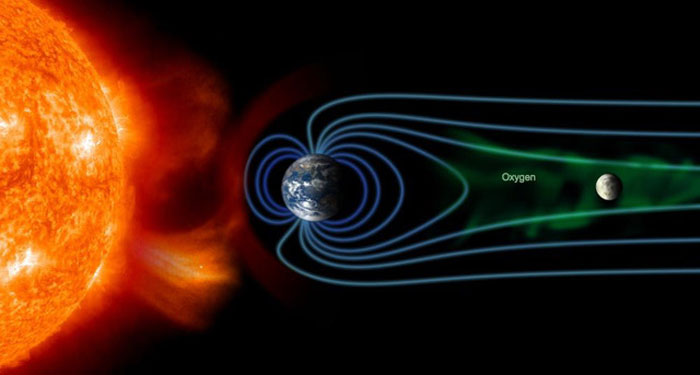

As you can see in the image directly above, the protective magnetic field isn't spherical, but envelops the planet in a teardrop shape, with the rounded edge of the teardrop facing the Sun, and the long tail – called the magnetotail – extending out behind Earth.

While the magnetosphere largely protects whatever's in it from solar radiation, the strength of the solar winds pushes some particles from Earth's atmosphere into a section of the magnetotail called the plasma sheet – which the researchers say is the most plausible explanation for how oxygen from Earth ends up embedded in the lunar soil.

"[Earth's] upper atmosphere consists of oxygen ions that are easily picked up by the solar wind and transported to the Moon," Terada explained to Rebecca Boyle at The Atlantic.

"Maybe some portion is implanted on the Moon, and some portion is lost into interplanetary space."

If the hypothesis is correct, it could mean that the Moon preserves ancient oxygen from when Earth's atmosphere was only very young, as far back as 2.5 billion years ago, the researchers suggest.

While the ability to examine that oxygen could be invaluable for scientists hoping to study the chemical makeup of our planet's atmosphere billions of years ago, these lunar traces of Earth's past might not prove a very convenient laboratory.

The Moon's surface is continually bombarded and altered by meteorites, which could have displaced the oxygen ions, or buried them deep under the lunar surface.

But scientists are still very much interested in looking at how this might be possible – now that we think the Moon could preserve ancient oxygen from Earth's past, there's a lot of intriguing new questions begging to be asked.

"For me, it was cool that a moon of a planet can preserve information about the planet, just from the solar wind," planetary scientist Craig Hardgrove from Arizona State University, who wasn't involved with the study, told The Atlantic.

"How you get the information out, that's a different paper."

The findings are reported in Nature Astronomy.