Scientists have drawn up the first ever map of areas of the US that would be at the biggest risk if a catastrophic geomagnetic storm – generated by solar energy erupting from the Sun – were to strike Earth.

While these kinds of intense geomagnetic storms are very rare, when they do hit, a stream of highly charged particles carried on the solar wind can disrupt Earth's magnetic field, causing havoc for electric power grids on the surface.

A particularly powerful solar ejection could potentially send us back to the Dark Ages for months or even years by causing widespread power outages around the planet, with a damage bill estimated to be as high as US$2.6 trillion.

So knowing which particular power grids stand to be hardest hit by such an intense solar storm is a pretty good idea – and that's the thinking behind the new map developed by researchers at the US Geological Survey.

"Power grids are grounded, so they can pick up electric fields generated deep inside the Earth," geophysicist Jeffrey Love told Dave Mosher at Business Insider. "But that geoelectric activity depends on the geology, and that's different from one region to the next."

In particular, areas at a higher latitude – and therefore closer to Earth's magnetic poles – receive the greatest barrage of particles during a solar storm.

Another factor at play is the conductivity of rock underneath regions with certain types of crust – such as sedimentary rock – that provide greater electrical conductivity (which you don't want in a catastrophic storm).

To assess which regions face the greatest risk from a geomagnetic storm, Love's team analysed geomagnetic data sourced from INTERMAGNET, a global network that monitors Earth's magnetic field.

They also looked at survey data from the US National Science Foundation's EarthScope program, which recorded electrical conductivity in the ground through a network of hundreds of sensors stationed across the country.

While the map doesn't yet cover the whole of the US, it's already revealing regions that we should be concerned about.

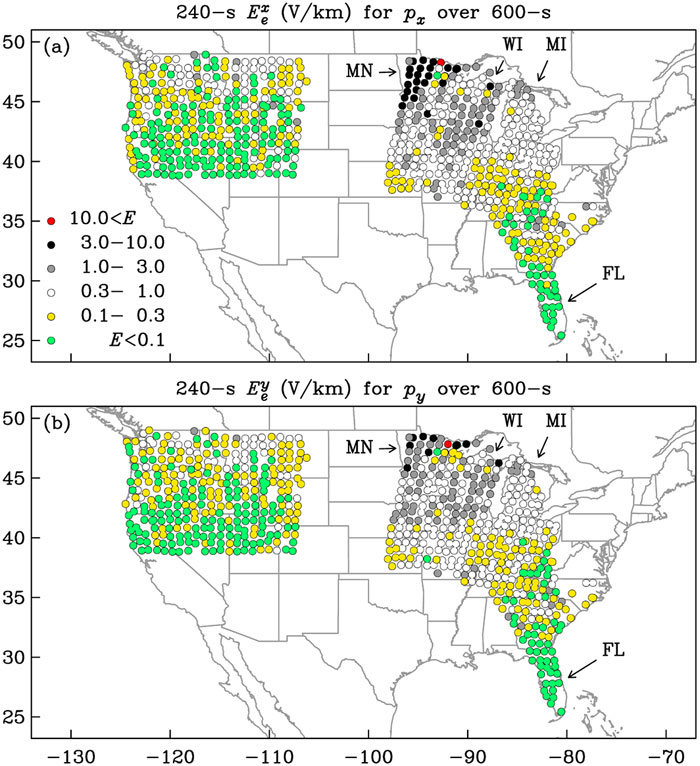

As you can see in the image below, Minnesota and Wisconsin are at a particularly high risk, with the red dots indicating where geoelectric hazards are at their most dangerous, followed by the black dots.

In comparison, the grey, white, yellow, and green dots are areas where geoelectric hazards pose less of a risk (in descending order of risk).

Love et al/Geophysical Research Letters

Love et al/Geophysical Research Letters

But as you can see, more than half the US hasn't been charted, as the researchers don't yet have congressional approval for the funding required to survey the rest of the country.

Love warns it's important to complete the work – especially the northeast US.

The researchers say the northeast region is a high-priority area in particular, due to its combination of high population metropolitan centres and corresponding grid infrastructure – but so far they're short the estimated US$500,000 it would take to survey the area.

"Hello, that's where a lot of people live," Love told Business Insider. "It's also where a lot of power grid infrastructure is located, and it's sitting on top of some complicated geology… Given the stakes, which are quite high, and the costs, which are quite low, it's worth it. $500,000 is about the price of a condo."

While intense geomagnetic storms only occur about every 100 years or so, it's only a matter of time until the next 'big one' hits, scientists say.

The last time that happened – the Solar Storm of 1859, aka the Carrington Event – telegraph systems across the US and Europe broke down.

In today's world, where society's reliance on electricity is greater than ever, the consequences of a Carrington-scale solar storm could be unthinkable.

But if we can figure out which parts of the grid are most at risk from a solar tsunami, it could give us a fighting chance to prepare our electricity networks and prevent them from overloading when the big one eventually hits.

"The hope is to help power utilities find out where their networks have weaknesses, how their systems might respond, and how they could alleviate problems," Love told Business Insider. "If we don't do it, we don't know what the risk is in the northeast."

The findings are reported in Geophysical Research Letters.