Our planet is restless, and its poles are wandering. Of course, the geographic north pole is in the same place it always was, but its magnetic counterpart – indicated by the N on any compass – is roaming towards Siberia at record-breaking speeds that scientists don't fully comprehend.

It's worth stating that while the pace is remarkable, the movement itself isn't. The magnetic north pole is never truly stationary, owing to fluctuations in the flow of molten iron within the core of our planet, which affect how Earth's magnetic field behaves.

"Since its first formal discovery in 1831, the north magnetic pole has travelled around 1,400 miles (2,250 km)," the NOAA's National Centres for Environmental Information (NCEI) explains on its website.

"This wandering has been generally quite slow, allowing scientists to keep track of its position fairly easily."

That slow wander has quickened of late. In recent decades, the magnetic north pole accelerated to an average speed of 55 kilometres (34 miles) per year.

The most recent data suggest its movement towards Russia may have slowed down to about 40 kilometres (25 miles) annually, but even so, compared to theoretical measurements going back hundreds of years, this is a phenomenon scientists have never witnessed before.

"The movement since the 1990s is much faster than at any time for at least four centuries," geomagnetic specialist Ciaran Beggan from the British Geological Survey (BGS) told FT.

"We really don't know much about the changes in the core that's driving it."

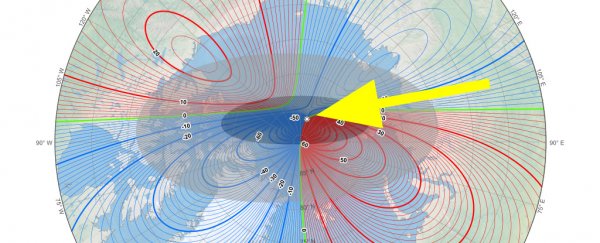

While researchers can't fully explain the core fluctuations affecting the north pole's extreme restlessness, they can map Earth's magnetic field and calculate its rate of change over time, which helps us to predict how it may be distributed in the future.

(NOAA NCEI/CIRES)

(NOAA NCEI/CIRES)

That system produces what is called the World Magnetic Model (WMM): a representation of the field that powers everything from navigational tools like GPS to mapping services and consumer compass apps, not to mention systems used by NASA, the FAA, and the military, among other institutions.

Despite its importance, the WMM's powers of foresight – like the magnetic north pole itself – are not set in stone, and the readings need to be updated every five years to keep the model accurate.

"Provided that suitable satellite magnetic observations are available, the prediction of the WMM is highly accurate on its release date and then subsequently deteriorates towards the end of the five-year epoch, when it has to be updated with revised values of the model coefficients," the NCEI explains.

That's the point we're up to now, with the bodies that maintain the WMM – the NCEI and the BGS – having finally updated the model last week.

The refresh actually comes a whole year ahead of schedule due to the unusual speed with which the magnetic north pole has been drifting, meaning that the WMM's predictions have deteriorated faster than usual this cycle, despite the recent slowdown.

While the speed fluctuations seem crazy, it's actually a more moderate range of pole movement than has happened in Earth's history: when the magnetic poles move far enough out of position, they can actually flip, something that happens every few hundreds of thousands of years.

There's no telling for sure when that might happen next, but if and when it does happen, it could have serious implications for humanity.

In the meantime, the new WMM data is good until 2025, and rest assured, no imminent flipping is predicted for now.