You'd think once a human is dead, the body would be done doing things; without blood circulation and air, the inner systems would be fast depleted. But due to a weird quirk of biology there are such things as the living dead - living cells, at least, within a done and dusted body.

Some cells within human brains actually increase their activity after we die. These 'zombie' cells ramp up their gene expression and valiantly continue trying to do their vital tasks, as if someone forgot to tell them they're now redundant.

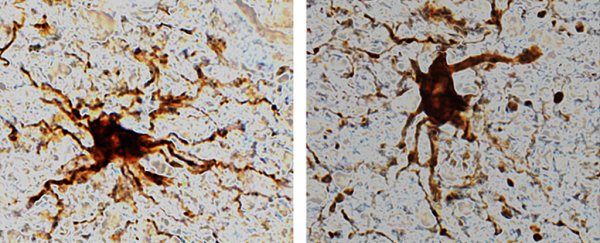

Neurologist Jeffrey Loeb from the University of Illinois and colleagues watched as these cells stubbornly sprouted new tentacles and busied themselves with chores for hours after death.

"Most studies assume that everything in the brain stops when the heart stops beating, but this is not so," Loeb said. "Our findings will be needed to interpret research on human brain tissues. We just haven't quantified these changes until now."

Much of the information we have on brain disorders like autism, Alzheimer's, and schizophrenia, comes from experiments performed on brain tissues after death; this approach is critical in the search for treatments, as animal models for brain studies often fail to translate back to us.

Usually, this work is done on tissues from people who've died more than 12 hours ago. By comparing gene expression in fresh brain tissues (removed as part of epilepsy surgery from 20 patients) to aforementioned brain samples from deceased people, Loeb and team found striking differences that were not age nor disease specific.

They used data on gene expression, which they later corroborated by examining the brain tissue's histology, to understand cell-specific activity changes across time since death, at room temperature.

While most gene activity remained stable for the 24 hours the team documented, neuronal cells and their gene activity rapidly depleted. Most remarkably though, glial cells increased gene expression and processes.

Cells come to life after death of the human brain. (Dr. Jeffrey Loeb/UIC)

Cells come to life after death of the human brain. (Dr. Jeffrey Loeb/UIC)

While surprising at first, this actually makes a lot of sense, given glial cells, such as waste-eating microglia and astrocytes, are called into action when things go wrong. And dying is about as 'wrong' as living things can go.

"That glial cells enlarge after death isn't too surprising given that they are inflammatory and their job is to clean things up after brain injuries like oxygen deprivation or stroke," said Loeb.

The team then demonstrated the RNA expressed by genes doesn't itself change within 24 hours post death, so any changes in its amount must indeed be due to the continuation of biological processes.

"The complete gene expression of freshly isolated human brain samples allows an unprecedented view of the genomic complexity of the human brain, because of the preservation of so many different transcripts no longer present in postmortem tissues," the researchers wrote in their paper.

This has huge implications for both past and present studies using brain tissue to understand diseases that involve immune responses - such as these 'zombie' glial cells that swell as they futilely devour surrounding bits of dying brains.

After 24 hours, however, these cells also succumbed and were no longer distinguishable from the degrading tissue that surrounded them.

"Researchers need to take into account these genetic and cellular changes, and reduce the post-mortem interval as much as possible to reduce the magnitude of these changes," Loeb explained.

"The good news from our findings is that we now know which genes and cell types are stable, which degrade, and which increase over time so that results from postmortem brain studies can be better understood."

Even in death, we biological entities are never entirely static.

This research was published in Scientific Reports.