For centuries, it's been the book no human can understand, but we may finally now be able to read it – thanks to machines invented a half-millennia after it was written.

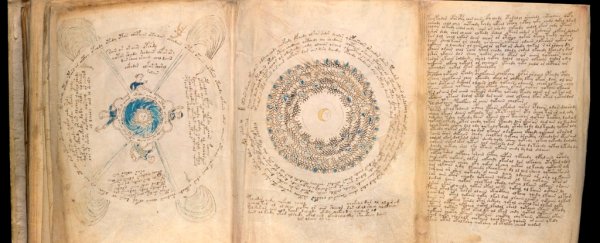

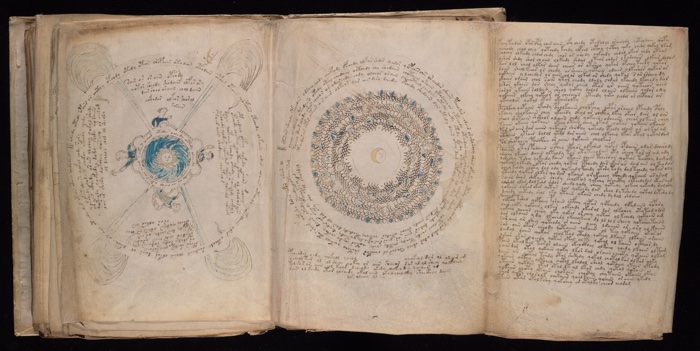

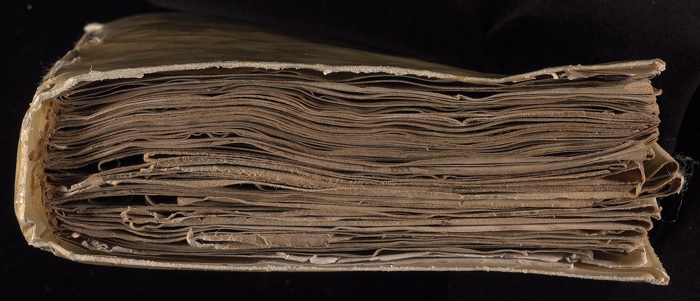

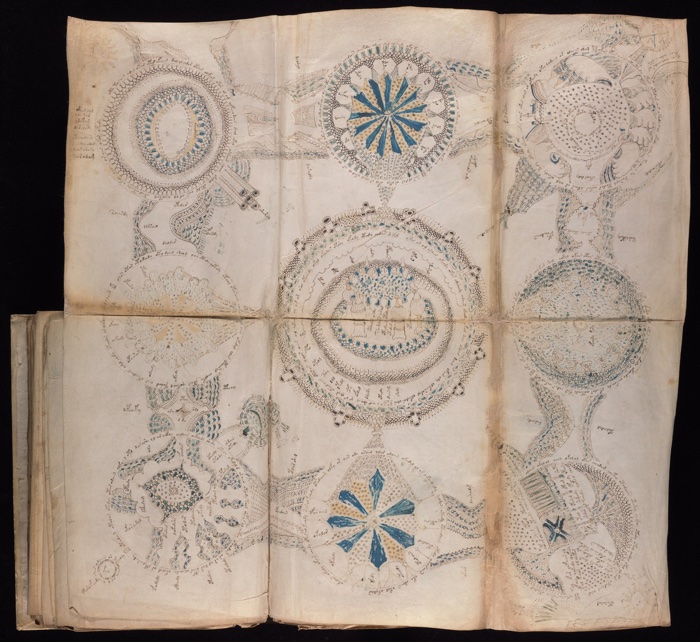

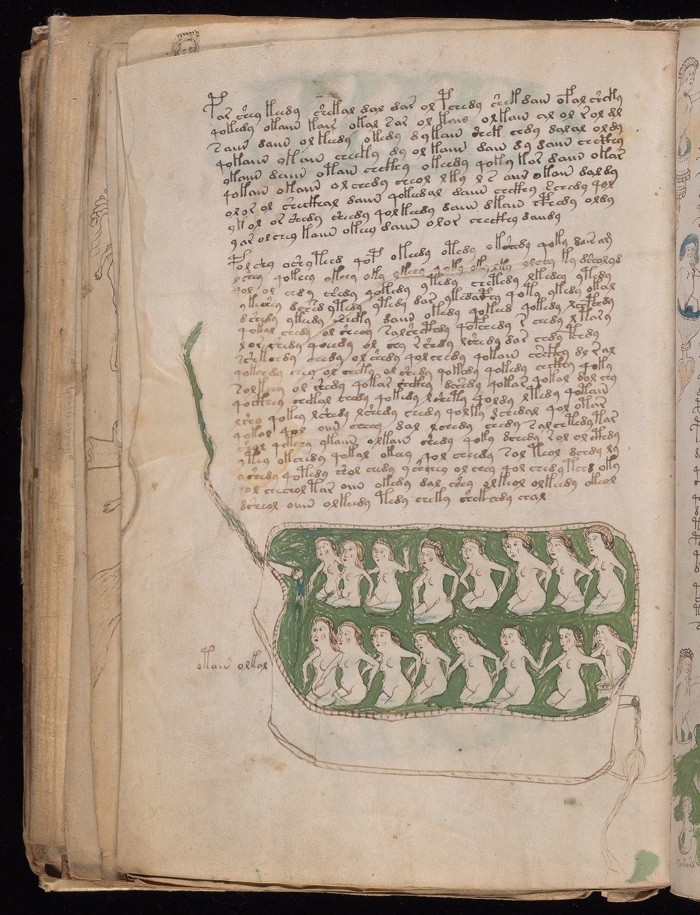

The Voynich manuscript, often called the world's most mysterious book, consists of some 240 pages of cryptic text written in an intricate, unknown language, accompanied by strange diagrams and illustrations. It even has fold-out pages, which is pretty nifty for a medieval tome dated to the early 15th century.

The thing is, nobody knows what the heck all this is getting at. The meanings of the text, inscribed on pages of ancient vellum, are thought to have eluded human comprehension for centuries.

It's been owned by alchemists and emperors, before surfacing in modern times in the early 20th century, when a Polish book dealer called Wilfrid Voynich chanced upon it in 1912, unwittingly lending the mysterious book his name.

(Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library)

(Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library)

Since then, any number of cryptographers, codebreakers, and linguists have attempted to unravel the secrets of the Voynich manuscript, but the obscure code contained in its pages – along with the strange drawings of plants, symbols, and bathing women – has defied explanation.

Now, thanks to Canadian computer scientists, it looks like we may have a new lead in the case.

Researchers from University of Alberta have used artificial intelligence to decode sections of the ancient manuscript, using a technique called algorithmic decipherment to reveal the underlying, encrypted language hidden behind the strange book's words.

(Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library)

(Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library)

It's not an easy thing to do, the team explains in their paper, given the number of unknowns involved.

"The Voynich manuscript is written in an unknown script that encodes an unknown language," the authors write, "which is the most challenging type of a decipherment problem."

Testing their algorithm on 380 different translations of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the researchers' system was able to correctly identify the language of origin 97 percent of the time.

(Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library)

(Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library)

Next, they focussed the AI on the pages of the Voynich manuscript, which the team suspected may be written in Arabic. The AI didn't agree, indicating Hebrew was the most likely source, edging out other potential matches that weren't commonly used for writing during the Middle Ages.

The researchers hypothesised the cipher acting on the Hebrew language could be an example of alphabetically ordered anagrams (called alphagrams), rearranging the order of letters in words, while dropping vowels.

Attempting to unscramble the the first 10 pages of the text with their AI produced mixed results.

"It turned out that over 80 per cent of the words were in a Hebrew dictionary, but we didn't know if they made sense together," says one of the team, computational linguist Greg Kondrak.

(Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library)

(Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library)

Failing to find any Hebrew scholars who could help validate their findings, the researchers eventually resorted to using Google Translate, but even though they acknowledge there's some guesswork involved, there does seem to be a match with the text.

In the opening section of the 'Herbal' chapter of the Voynich manuscript, which contains drawing of several kinds of plants, many botany-related terms appear, including farmer, light, air, and fire.

Coincidence? Maybe not.

As for how the most mysterious book in the world starts? Well, fairly ambiguously as it turns out, but would you expect anything else?

"She made recommendations to the priest, man of the house and me and people," are the Voynich manuscript's first words, according to the AI.

Recommendations to do with herbal botany, perhaps? The team says we can't be sure.

"It came up with a sentence that is grammatical, and you can interpret it," says Kondrak. "It's a kind of strange sentence to start a manuscript but it definitely makes sense."

That said, the team acknowledges they'd need the assistance of ancient Hebrew historians to take their decoding further, and to confirm we're not conjuring algorithmically-derived misinterpretations out of the Voynich haze.

"The results presented in this section could be interpreted either as tantalising clues for Hebrew as the source language of the [Voynich manuscript], or simply as artefacts of the combinatorial power of anagramming and language models," they write.

"In any case, the output of an algorithmic decipherment of a noisy input can only be a starting point for scholars that are well-versed in the given language and historical period."

Given how much we still don't know, it's an exciting new lead for further investigations into decoding the ancient puzzle, not that everybody in the Voynich-obsessed cipher community is necessarily convinced by the team's AI-based approach.

"I don't think they are friendly to this kind of research," Kondrak told The Canadian Press, but he points out that there's a real opportunity for further discoveries here if the Hebrew hypothesis is on point after all.

"Somebody with very good knowledge of Hebrew and who's a historian at the same time could take this evidence and follow this kind of clue. Can we look at these texts closely and do some kind of detective work and decipher what can be the message?"

The findings are reported in Transactions of the Association of Computational Linguistics (link down at time of writing).