A spectacular discovery in south China is shedding more light on the mysterious lifeforms that crawled our planet half a billion years ago. In a shale bed next to Danshui River, palaentologists have excavated around 30,000 fossils dating back to the Cambrian period 518 million years ago.

The newly discovered exquisite fossil bed, what is known as a Lagerstätte, could rival the Cambrian-era Burgess Shale in scope and importance.

The researchers have analysed 4,351 specimens of the epic find, identifying 101 multicellular species and eight algae. Around 53 percent of these are totally new to science, which could help us understand more about the mysterious explosion of animal life on Earth.

Collectively, the lifeforms are known as the Qingjiang biota.

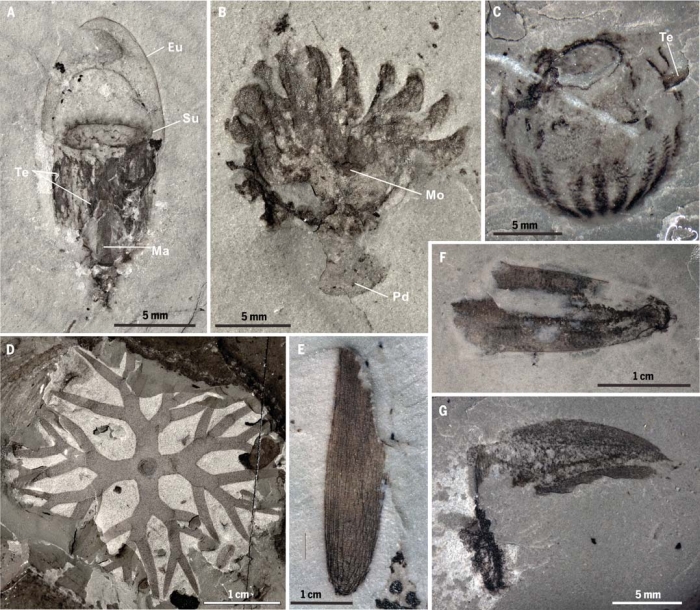

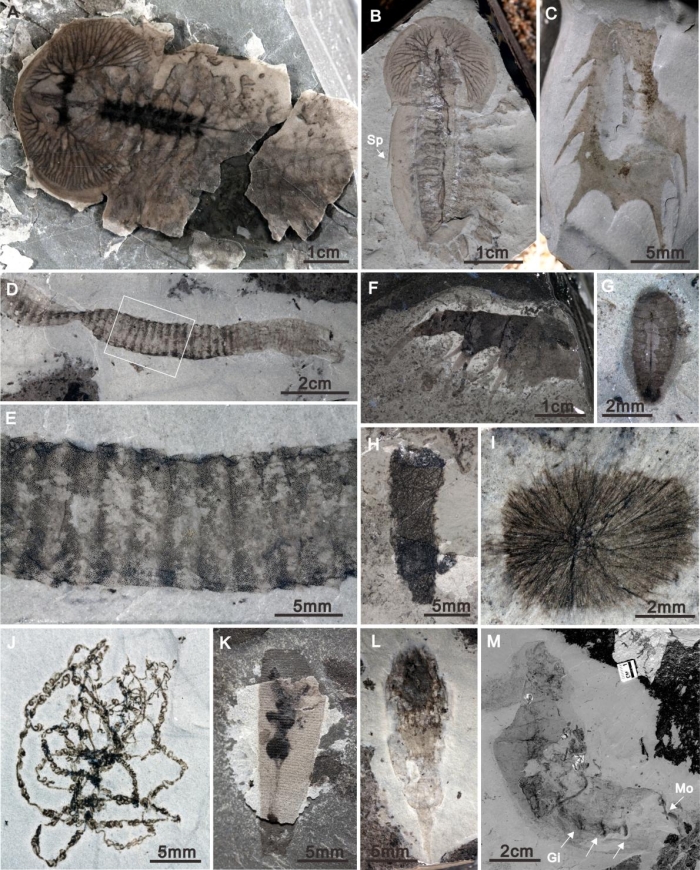

(Fu et al., Science, 2019)

(Fu et al., Science, 2019)

It's thought that multicellular life emerged during the Ediacarian Period that started 635 million years ago. Then, 541 million years ago, it gave way to the Cambrian - and an event known as the Cambrian explosion.

This is exactly what it sounds like - suddenly most of the major animal phyla appeared on the fossil record over a period of about 25 million years in marine ecosystems around the world. These would eventually diversify to produce pretty much all modern multicellular life. What a time to be alive!

But time is a monster that degrades tissue, and as a result that fossil record is rather patchy, confined to a handful of well-preserved shale beds around the world.

There's the aforementioned famous Burgess Shale, in Canada, and the Maotianshan shale beds of Chengjiang in China, as well as shale beds in Sweden, Poland, the US, Australia and Greenland.

During the Cambrian, these shale beds were fine silt mud on seafloors; ocean creatures died and fell to the seafloor, and were buried by falling silt. Then a long, slow geological process preserved their strange bodies - heat and pressure hardening the silt into shale, but not so much that it destroyed the fossils therein.

So incredible is this preservation process that it captured detailed impressions even of soft-bodied creatures for us to goggle at, millions of years later.

"Most fossil localities throughout all of time are going to preserve the shelly things, the hard things … [but] what these localities give you is anatomy," palaeontologist Joanna Wolfe of Harvard University, who wasn't involved in the study, told National Geographic.

"These are the best of the best."

What makes this find so spectacular is that it fills gaps. Jellyfish, box jellies, anemones, branched algae and sponges proliferate, where they are scant or missing from other deposits.

And they are much better preserved than the Burgess and Chengjiang deposits, undamaged by the metamorphic processes that affected the former fossils, and the weathering on the latter.

Soft-bodied creatures of the Qingjiang biota. (Fu et al., Science, 209)

Soft-bodied creatures of the Qingjiang biota. (Fu et al., Science, 209)

In fact, the preservation level is so exceptional that even jellyfish tentacles and comb jellies can be made out in detail.

"This is where the Qingjiang biota is truly remarkable, and certainly worthy of attention, by how it presents its members with amazing detail of shapes, antennas or eyes," geobiologist Emma Hammarlund of Lund University told Eos.

"The rocks are much less weathered than at Chengjiang and less cooked than at Burgess Shale."

Because the deposit is contemporaneous with Chengjiang, the researchers believe that the differences between the two indicate how the two ecosystems formed in different paleoenvironmental contexts.

The deposits were discovered in 2007, and the team has completed four seasons of field work in that time. There's still a lot of work to do to analyse and catalogue the remaining fossils, and more fieldwork could yet turn up even more.

We don't know what surprises still lie therein, preserved in stone, but one thing seems certain: this discovery is going to mean great things for our understanding of animal evolution.

The research has been published in Science.