Our neighbourhood in space is turning out to be quite the populous planet precinct. Astronomers have found a new exoplanet just a little bit bigger than Earth, orbiting a red dwarf star just 66.5 light-years away.

It's an excellent candidate, they say, to help fill our vast knowledge gap about the small, rocky planet population of our Milky Way galaxy.

Our detection ability and knowledge of exoplanets has practically exploded since the first discovery was published in 1992. At time of writing, over 4,100 exoplanets have been confirmed in our galaxy, and we now have a much deeper understanding of planetary systems and how they form and evolve.

But, since we're looking for small, dim or dark things that are very hard to see from a distance, naturally most of the confirmed exoplanets are the chonkers - ice and gas giants the size of Neptune and above.

The Kepler exoplanet-hunting missions, and now TESS, have been increasing the number of detections of smaller exoplanets: those around the mass of Earth and Venus, and therefore likely to be rocky, rather than gaseous. (That's one of the prerequisites for life as we know it.)

But, according to an international team led by astrophysicist Avi Shporer of MIT's Kavli Institute for Astrophysics and Space Research, these rocky planets are hard to measure and hard to characterise. That's because we don't often find them around stars that are bright enough to allow for detailed follow-up investigations.

That's why the discovery of this new exoplanet is so cool. The team's paper has been uploaded to arXiv, and is yet to be peer reviewed, but their results are tantalising, to say the least.

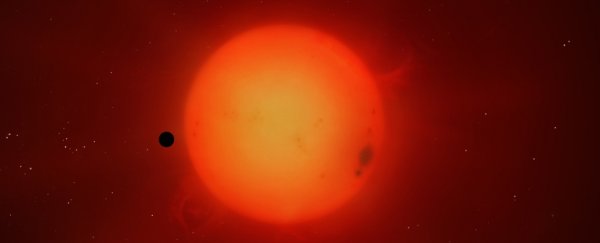

"Here we present the discovery of GJ 1252 b, a small planet orbiting an M dwarf. The planet was initially discovered as a transiting planet candidate using TESS data," the researchers write.

"Based on the TESS data and additional follow-up data we are able to reject all false positive scenarios, showing it is a real planet."

GJ 1252 b is around 1.2 times the size of Earth, and around twice Earth's mass (so a bit denser than our home planet). It's orbiting a red dwarf star called GJ 1252, which is a little scrap of a thing, around 40 percent of the size and mass of the Sun.

The exoplanet whips around its star once every 12.4 hours - way too close for habitability, and probably tidally locked, where one side is always facing the star - but that tight orbit makes it attractive for another reason.

At just 66.5 light-years away, the system is at a close-enough distance that the star is bright enough for those follow-up observations we mentioned. In addition, the red dwarf is unusually calm for a star of its type; and the fact that the planet orbits it so often means there are plenty of opportunities to catch it moving in front of its host.

This is called a transit, and if the planet has an atmosphere, it will be back-lit by the star's light during transits, potentially allowing astronomers to see what's in it using spectroscopic observations.

And here's the other cool thing: GJ 1252 b is just the latest in a few of these nearby rocky worlds that TESS has found.

Pi Mensae c and LHS 3844 b, 60 and 49 light-years away respectively, were announced in September of last year; TOI-270b is 73 light-years away; Teegarden b and Teegarden c are 12.5 light-years away; and Gliese b, Gliese c and Gliese d are 12 light-years away.

The more of these nearby rocky planets we find, the more data we can compile on them to figure out how common they are, and what they are like - whether Earth is a total weirdo, and most rocky planets are barren wastelands like Mercury, Venus and Mars, or actually a more common type of planet in the Milky Way.

And, of course, that has implications for the search for extraterrestrial life as well. But first, we need to see more rocky exoplanets. GJ 1252 b could be an excellent place to start.

"The host star proximity and brightness and the short orbital period make this star-planet system an attractive target for detailed characterisation," the researchers wrote in their paper.

"These investigations include studying the planet's atmosphere, and using future Gaia astrometric data, combined with long term radial velocity monitoring, to look for any currently unknown star, brown dwarf, or massive planet orbiting the host star."

The research has been submitted to the American Astronomical Society, and is available on arXiv.