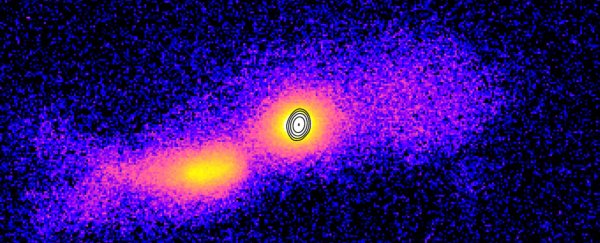

Space can be a horror show of cosmic violence, and now astronomers have captured the first photographic evidence of the carnage that can be unleashed when two heavyweight galaxies collide.

A collaboration between an international team of researchers has produced the first ever image of a relativistic jet of gas and plasma spewing forth from a pair of galaxies as they dive head-first into one another.

While galaxies have been caught mid-collision plenty of times before, this is the first time a jet of this kind has been seen spilling out of such a merger, and it could tell us a thing or two about how they arise.

In this case, both offending galaxies have gargantuan black holes at their centres that draw material into a maelstrom so violent, it glows intensely with heat.

Such radiant cores are called active galactic nuclei, or AGN, and they can emit more energy in a single second than our poor old Sun will ever hope to produce in its lifetime.

Roughly 15 percent of all AGNs happen to have the right conditions to also shoot streams of plasma from their poles, effectively creating a pair of light sabres that cross intergalactic space.

Most giant laser beams are directed away from our viewpoint. We call those quasars. But every now and then they can be found pointing in our direction, allowing us to look down the barrel of a jet of near light-speed particles from a safe distance.

TXS 2116-077 just happens to have one of those types of AGN, which is good news for astronomers eager to analyse its full spectrum.

But there's something a little odd about this particular light show.

"Typically, a jet emits light that is so powerful we can't see the galaxy behind it," explains astronomer Stefano Marchesi from the Observatory of Astrophysics and Space Science in Bologna.

"It's like trying to look at an object and someone points a bright flashlight into your eyes. All you can see is the flashlight. This jet is less powerful, so we can actually see the galaxy where it is born."

It appears that this particular beam is only just warming up. The fact that its parent galaxy behind it can be seen burying itself into the heart of another galaxy gives researchers a good clue that helps explain the beam's youth.

Brighter AGNs are usually found inside galaxies peppered with relatively young stars, potentially reflecting the rich pickings of star-forming (and black-hole feeding) clouds of material.

Strangely, those that produce jets tend to be older, elliptical galaxies.

The two involved in this collision are on the younger side and shaped like discs, but the fact they have little gas and other hazy material scattered through them suggests this isn't the first dust-up they've had together.

Putting the pieces together, the researchers believe it requires some colossal jostling for clouds of dust and gas to rain down onto an AGN, where it's spun into a heated frenzy before being shot far out into the Universe again.

"It's hard to dislodge gas from the galaxy and have it reach its centre," says astronomer Marco Ajello from Clemson University.

"You need something to shake the galaxy a little bit to make the gas get there."

Eventually all of the material within the black hole's reach will be spat out or swept away, leading to a period of relative peace and quiet where the AGN cools down and stars are no longer being formed.

The finding has implications for how we interpret jets from other elliptical galaxies full of older stars, pointing to collisions as crucial features in their evolution.

With our own Milky Way destined to join up with the neighbouring Andromeda in around 4.5 billion years (give or take), we might expect a similar show of blood and guts to occur.

Our galaxy's black hole isn't active, but with a good shake-up, anything is possible.

"Scientists have carried out detailed numerical simulations and predicted that this event may ultimately lead to the formation of one giant elliptical galaxy," says physicist Vaidehi Paliya from Germany's Deutsches Elektronen Synchrotron.

"Depending on the physical conditions, it may host a relativistic jet, but that's in the distant future."

This research was published in the Astrophysical Journal.