With an expanding waistline comes a concerning list of health concerns. But for a while now, the jury has been out on exactly how weight gain impacts what's between our ears.

A new study suggests it's not great. The research provides strong evidence that links extra body mass – particularly fat carried around the belly – to a troubling decrease in brain volume.

Just how this extra fat impacts our brain's function isn't clear, but with past research linking obesity with neurological conditions, it doesn't seem positive.

"Existing research has linked brain shrinkage to memory decline and a higher risk of dementia, but research on whether extra body fat is protective or detrimental to brain size has been inconclusive," says lead author, Mark Hamer of Loughborough University in England.

Some studies have hinted at a decline in some types of brain cell with a rise in body fat levels, showing a potential cause for elevated risk of neurological conditions.

But not all researchers agree on findings, especially when weight can fluctuate in the years preceding a diagnosis of dementia.

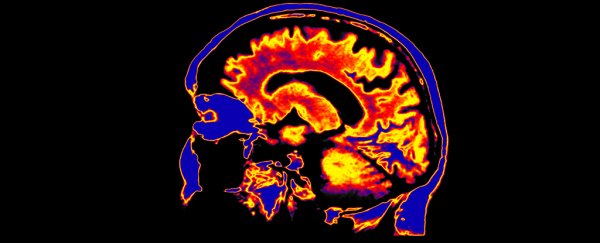

To try to unravel the details, researchers in this latest study compared body mass index (BMI) measurements and waist-to-hip ratios with both the volume of signal-carrying nervous tissue called 'grey matter' and the supportive 'white matter' tissue.

Each factor has been examined on its own previously – the difference this time was examining them as a joint effect between waist-to-hip ratios as well as BMIs.

Just under 10,000 participants were involved in the study, ranging in age from 40 to nearly 70 years. All had participated in a recent UK based 'Biobank' survey, during which they'd had their bodies scanned with magnetic resonance imaging ( MRI) equipment.

Measurements of height and overall body weight were used to calculate a body mass index score – a traditional, if somewhat flawed, indicator of obesity. Body fat masses were also recorded and combined with other details to provide a mediating fat index score.

Waist and hip circumferences were also measured to come up with yet another measurement indicative of weight gain.

This gave the research team a bank of anatomical information to sift through and compare. Just under one in five of the sample qualified as being obese, most of which were less likely to be physically active, and more likely to have heart disease and high blood pressure.

Taking other factors into account that could produce differences in brain volume – such as age, smoking, and exercise – the team found body mass index alone could be linked with a slight drop in the volume of grey matter.

But having both a high BMI with a high waist-to-hip ratio turned out to be the real concern.

Roughly 1,300 subjects fells into this category. On average, they had a grey matter brain volume of just 786 cubic centimetres.

By comparison, the 3,000-odd individuals with a healthy BMI and waist-to-hip ratio averaged a volume of 798 cubic centimetres, while those with a high BMI and a relatively slim waistline came in at 793 cubic centimetres.

While the study can show a relationship, the nature of this link is still up for debate. It's possible that excess fat could be impacting the central nervous system by way of the cardiovascular system.

There's also the usual warning to avoid jumping to conclusions on which way the relationship runs. Studies like these can't rule out the possibility that a loss of grey matter somehow makes it harder to lose weight.

Unfortunately, most individuals who were contacted to participate in the research declined. The tiny proportion who volunteered tended to be somewhat healthier, which needs to be kept in mind when considering the results.

Still, the research makes a compelling case for looking closely at the connection between obesity and neurology.

"We also found links between obesity and shrinkage in specific regions of the brain," says Hamer.

"This will need further research but it may be possible that someday regularly measuring BMI and waist-to-hip ratio may help determine brain health."

With so many findings linking the physiology of our gut with the functioning of our brain, it shouldn't come as much of a surprise that body fat and brain volume are somehow connected.

No doubt the closer we look, the more complex this relationship will prove to be.

This research was published in Neurology.