Scientists have uncovered a new molecular pathway connecting the gut with the brain, and if we can learn how to control it, we may be able to slow down or even stop multiple sclerosis and other neurological disorders, scientists say.

The new research is the latest in a wave of recent discoveries about how the brain and gut are linked together, affecting everything from our emotions to our neurological health and more – and the latest study suggests we can influence that link.

"We essentially discovered a remote control by which the gut flora can control what is going on at a distant site in the body, in this case the central nervous system," lead researcher and neurologist Francisco Quintana from Harvard University told Forbes.

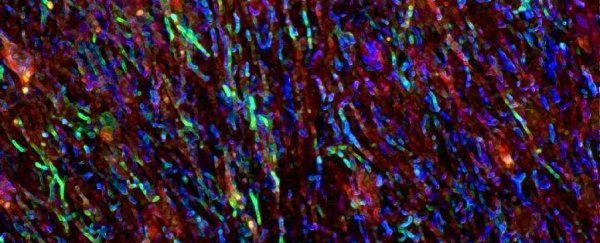

That remote control is based around two different types of cell involved in how our central nervous system functions: microglia and astrocytes.

Microglia are immune cells that play a vital role in brain health, by scavenging through the central nervous system and devouring old and damaged cells that can contribute to inflammation.

Another kind of brain support cell, called astrocytes, can also prevent inflammation. The thing is, astrocytes can promote inflammation as well, and the control switch over this alternating behaviour has never been entirely clear.

Previous research from members of the same team in 2016 found astrocyte functioning could be influenced by dietary impact on gut bacteria – specifically how metabolite molecules derived from the amino acid tryptophan were linked to astrocytes reducing inflammation.

Researchers already knew microglia regulated astrocyte behaviour as part of this process, but what we didn't know was how the nature of the regulation was determined.

Now, the team has figured it out.

In their new study, the researchers investigated the effect of dietary changes on mice with a mouse form of multiple sclerosis.

What they found was the level of tryptophan consumed affects the overall microglial production of two proteins, called TGF alpha and VEGF-B.

TGF alpha is good – it binds to receptors on the astrocytes, preventing them for causing inflammation. The other protein, VEGF-B, also binds to astrocytes, but in a way that makes the support cells promote inflammation in the central nervous system.

"One of the biggest unanswered questions we had is: what mediates the crosstalk between microglia and astrocytes?" Quintana told The Scientist.

"VEGF-B seems to boost pathogenic or pro-inflammatory responses of astrocytes, while TGF alpha does exactly the opposite."

The researchers acknowledge there's still a lot more to be deciphered in this area, as the tryptophan discovery could just be the start.

"Multiple bacterial metabolites could be activating the pathways," Quintana explained to Forbes.

"We have currently focused on just one metabolite."

Future research will explore whether other metabolites are involved too, as well as whether other kinds of astrocyte receptors are also affected by molecules released by gut bacteria.

Ultimately the team hopes to be able to control this process therapeutically, using targeted chemicals to activate this anti-inflammation channel inside our metabolism – which could one day help patients with multiple sclerosis and lots of other neurological conditions.

Until then, there's no advice to change what you eat, but it's good to know that dietary formulations are part of the puzzle scientists are unravelling here.

"We are a long way away from being able to make recommendations about diet in MS. It's premature to recommend any dietary changes or interventions," executive VP of research at the National MS Society, Bruce Bebo, whose organisation helped fund the research, explained to Forbes.

"We hope that within the next few years, drugs can be found for trials and tested in patients."

The findings are reported in Nature.