To call the Universe vast would be an understatement. It is, as far as we know, without boundary - so big that we don't even know if it's finite or not. Either way, the space we can observe is teeming with fascinating objects, interactions, stars, galaxies, gases, dust, rocks, and planets.

It's useful, in our study of the cosmos, to give names to these things. Most of these names are purely functional, based on things like coordinates and the survey that discovered it, like the star SMSS J160540.18–144323.1 or the quasar ULAS J1342+0928.

Some are more poetic. Stellar streams. The Cosmic Snake. Blazars. The Andromeda Galaxy. The constellation of Lyra.

But humans are cheeky creatures. And some of the things out there in space have cute, silly, or downright strange names that just make you go "wait, what the heck is that?"

Here are some of our favourite really weird names for really awesome things.

Sualocin and Rotanev

(Pithecanthropus4152/Wikimedia Commons/CC BY-SA 4.0)

(Pithecanthropus4152/Wikimedia Commons/CC BY-SA 4.0)

If you know anything at all about star names, these two should immediately stick out like a sore thumb. They're not the usual Arabic or Latin names; in fact, they're not words in any language. But they do follow another star-naming convention, after a fashion.

They're names given to two binary star systems in the northern constellation of Delphinus (the Dolphin), designated Alpha Delphini and Beta Delphini, and they were named after a person - Italian astronomer Niccolò Cacciatore.

In the early 19th century, he worked with Giuseppe Piazzi, the head of the Palermo Astronomical Observatory, who was putting together a catalogue of stars, published in 1814. It was in this catalogue that the names Sualocin and Rotanev first appeared.

If you write those two names backwards, you get the Latin name Nicolaus Venator. In English, it's Nicholas Hunter. In Italian? Niccolò Cacciatore. The two names have since been approved by the International Astronomical Union.

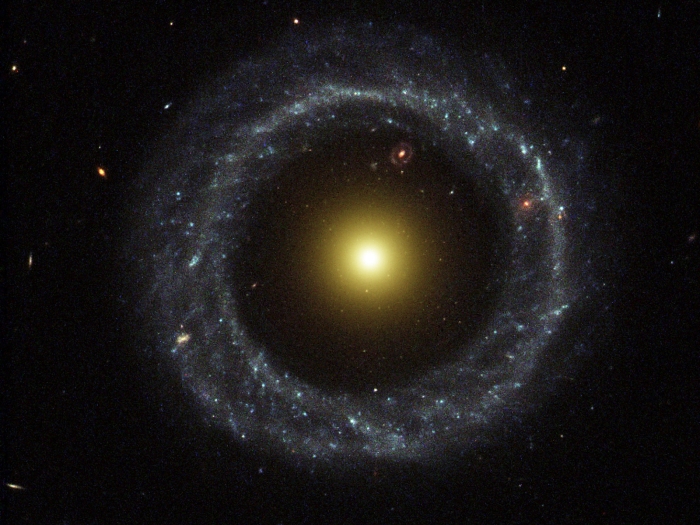

Hoag's Object

(NASA/ESA and The Hubble Heritage Team/STScI/AURA)

(NASA/ESA and The Hubble Heritage Team/STScI/AURA)

When astronomers don't know what something is, they call it an object, so this name isn't as strange as it might seem. We didn't know what Hoag's Object was when it was discovered in 1950; as it was discovered by American astronomer Arthur Hoag, it was named after him.

Hoag suggested that the curious appearance of the object was an optical illusion, but follow-up observations in the years since its discovery have revealed the object's true nature. Hoag's Object is a really rare kind of galaxy called a ring galaxy, about 600 million light-years away. In that exclusive category, Hoag's Object is unique.

It consists of a perfectly symmetrical ring of young, blue stars and stars in formation across about 125,000 light-years, perfectly circling a yellow sphere of older stars about 17,000 light-years across.

The two components are separated by what appears to be an empty gap 58,000 light-years across; it could contain star clusters too faint for us to see at this distance, though.

How did it get this way? We don't know. There's no evidence of a collision that could have punched a hole through it, as seen in other ring galaxies (and such a collision would be unlikely to leave such a tidy wake - no other ring galaxy is so symmetrical). To date, Hoag's Object remains a baffling, glorious mystery.

Hanny's Voorwerp

(NASA/ESA/W. Keel/University of Alabama/Galaxy Zoo Team)

(NASA/ESA/W. Keel/University of Alabama/Galaxy Zoo Team)

It's another weird object! Voorwerp means 'object' in Dutch, which makes Hanny's Voorwerp Hanny's Object. It was discovered by citizen scientist and school teacher Hanny van Arkel in 2007 as part of the volunteer Galaxy Zoo project, and boy is it an oddball.

It's a glowing glob of gas floating in space right next to what seems to be an otherwise perfectly normal galaxy 650 million light-years away.

Follow-up research revealed it to be a rare object called a quasar ionisation echo. The gas is just one relatively small section of a streamer around 300,000 light-years long that wraps around the galaxy, pulled out by a gravitational interaction with another galaxy. The rest of the streamer is invisible.

The part we see was illuminated because, not so long ago, the galaxy had a quasar nucleus – an extremely bright region powered by an active supermassive black hole. This ejected a beam of radiation out into space, catching a section of the streamer and ionising the gas therein, causing it to glow.

Other such ionised galactic gas streamers were later identified; they have been nicknamed Voorwerpjes.

Dark Doodad

(Naskies/Wikimedia Commons/CC BY-SA 3.0)

(Naskies/Wikimedia Commons/CC BY-SA 3.0)

There are a lot of nebulae out there with really interesting, descriptive names. You know what you're getting with the Horsehead Nebula or the Pacman Nebula.

Then there's the Dark Doodad. It was given that nickname by amateur astronomer Dennis di Cicco in 1986, and it just sort of stuck. Despite the goofy name, the Dark Doodad is really wonderful - resembling a dark crack in space that's otherwise teeming with stars.

The Dark Doodad is actually in front of them, though, being one of the clearest examples of what's called a dark nebula.

When you think of nebulae, you probably think of glimmering, glowing, gorgeously hued and complex clouds of gas and dust stretching light-years across, but these space clouds come in several flavours.

There are emission nebulae; the gas in them glows, ionised by hot, bright stars. Then there are reflection nebulae; the gas in them doesn't glow, but it reflects the light of stars nearby.

The third kind are called dark nebulae. They neither produce nor reflect light, and they block the light of stars behind them. Rather than shimmering space rainbows, they appear as vast, shadowy voids in the cosmos.

Gomez's Hamburger

(NASA and The Hubble Heritage Team/STScI/AURA)

(NASA and The Hubble Heritage Team/STScI/AURA)

Whoever named Gomez's Hamburger sure must have been hungry, because it doesn't really look much like a hamburger.

The object was discovered in 1985 in images taken by Arturo Gomez of the Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory in Chile, and it was initially identified as a planetary nebula around a very old, dying star. But if it was a planetary nebula, it was an odd one, with a dark band stretching across the glowing centre.

It wasn't until 2008 that astronomers suggested Gomez's Hamburger might actually be the opposite; not an old star 6,500 light-years away, but a very young one, just 900 light-years away, around four times the mass of the Sun. So young, in fact, that it is still surrounded by a protoplanetary disc of dust and gas.

In this model, the bright regions - the burger's buns - are starlight reflecting off dust around it. The burger's filling is that protoplanetary disc, seen edge-on.

Moon-moons

Dwarf planet Eris and its moon Dysnomia. (NASA/JPL-Caltech)

Dwarf planet Eris and its moon Dysnomia. (NASA/JPL-Caltech)

Supermassive black holes are orbited by stars. Stars are orbited by planets. Planets are orbited by moons. So what the heck are moons orbited by?

Well, we've never actually spotted anything orbiting a moon. But it is theoretically possible, as astronomers laid out in 2018. They ran simulations to determine if a moon could have its own satellite, and found that yes, it could, if the circumstances were just right.

This satellite would need to be close enough to the moon to be bound by its gravity, not the gravity of the planet; but not so close that it gets torn apart by tidal forces. That means they're probably really rare - but not actually impossible.

And we even have a name ready and waiting if we ever do detect them - moon-moons. Yes please, thank you very much.

The Great Annihilator

Quiet black holes are pretty hard to find, but every now and again they do something spectacular. And spectacular is exactly what we've got with a black hole called 1E1740.7-2942.

It's a stellar-mass black hole, which in the early 1990s was observed to be spewing out X-rays along with relativistic jets, as it devoured mass from its companion star.

But that's not all. Astronomers also detected it emitting gamma radiation at 511 kiloelectronvolts - the energy signature produced when an electron-positron pair annihilate each other, producing a pair of photons.

And this inspired the object's ridiculously badass nickname - the Great Annihilator.

The Great Annihilator was later identified as a microquasar, the stellar-mass version of quasar galaxies, which in turn are some of the most luminous objects in the entire Universe, as their supermassive black holes accrete matter at a tremendous rate.

Alpha Boo

(ESO/Digitised Sky Survey)

(ESO/Digitised Sky Survey)

You may know the fourth brightest star in our night sky as Arcturus, and a good, noble name it is too. It's been in use since the time of the Ancient Greeks, meaning 'Guardian of the Bear'. The star is close to the constellation of Ursa Major, the Great Bear.

But it's not part of Ursa Major. The 7.1 billion-year-old red giant belongs to the constellation of Boötes, the Herdsman. And because the brightest star in a constellation is typically the Alpha star - the others follow the Greek letters of the alphabet in order of decreasing apparent brightness - its designation is α Boötis, or Alpha Boötis.

You can see where this is going, no doubt - the most adorable abbreviation of a star name ever. Alpha Boo.

Someone really needs to put "Be my Arcturus" on Valentine's Day cards.