If El Niños were dangerous before, they are looking to become especially destructive in the near future. Already severe and unpredictable, recent research indicates these natural weather events are now swinging to even greater extremes.

Since humans started burning fossil fuels on an industrial scale, coral records from the past 7,000 years indicate that heat waves, wildfires, droughts, flooding and violent storms associated with El Niño have grown markedly worse.

It's still unclear whether this is due to climate change directly, but from the limited history we have, the pattern of both looks suspicious.

"What we're seeing in the last 50 years is outside any natural variability," says earth and atmospheric scientist Kim Cobb from the Georgia Institute of Technology.

"It leaps off the baseline. Actually, we even see this for the entire period of the industrial age."

Climate scientists have long suspected a cause-and-effect relationship between global warming and El Niño, but while some studies have shown stronger and longer events with growing global temperatures, others have found the opposite.

The El Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO) is a natural weather cycle that has heated and cooled the equatorial Pacific ocean for thousands of years, causing large-scale weather changes. Predicting when, where and how this pendulum will swing, however, has proved quite difficult.

Usually showing up every two to seven years, El Niño events are known to cause brief spikes in global surface temperatures, whereas La Niña events trigger the opposite cooling effect.

Still, reliable ENSO measurements only go back about a century, so it's been hard to determine if these changes are 'normal' in the grand scheme of things.

Thankfully, just like the rings of a tree, coral forests also keep records of the past. As living coral slowly adds calcium-carbonate layers to its hard shell, chemicals in each band of growth trap remnants of the ocean from long ago.

Using coral as a proxy for previous climates, recent analysis suggests El Niño events are already intensifying with greenhouse warming. Earlier this year, a study on coral found that Eastern Pacific El Niño events have become fewer, but more intense in the past 30 years than in the past four centuries.

Just a month or so ago, a study on 33 events from the past century found that since the late 1970s, Central Pacific El Niños have started originating in a warmer part of the Pacific ocean, increasing the risk of reaching peak intensity.

Now, reaching back in the coral record further than ever, researchers have once again found a similar pattern. Evidence from the Line Islands in the Pacific suggests El Niño events are already growing worse along with anthropogenic climate change.

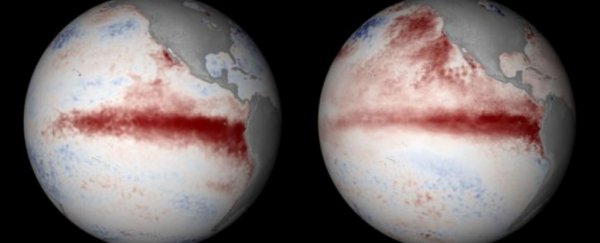

(NOAA)

(NOAA)

Reconstructing ENSO variations over the last 7,000 years in this one small corner of the ocean, researchers found El Niño events have grown 25 percent stronger since pre-industrial times.

"There were three extremely strong El Niño-La Niña events in the 50-year period, but it wasn't just these events," says Cobb.

"The entire pattern stuck out."

Indeed, even when the most extreme El Niño events were removed from the coral dataset, the results still showed an intensification of ENSO extremes over time. Although, to be statistically significant, the super powerful El Niño from '98, which caused one of the worst coral bleaching events in recorded history, had to be included.

"While there is no a priori reason to exclude this event from our analysis," the authors write, "this finding does illustrate that we may have only recently exceeded the detection limit for observing enhanced variability in ENSO properties."

In other words, things are just starting to pick up speed. Research from 2014 found that since the turn of the century, super El Niños have doubled, going from one every 20 years to one every 10 years.

Whether climate change is causing this intensification is another matter entirely. El Niño events are known to exacerbate the worst of the climate crisis, but is climate change somehow amplifying El Niños too?

Depending on who you speak to, maybe, maybe not; there's still no consensus on the issue. But no matter what the cause, it's becoming increasingly clear that something unusual is happening to one of the world's most important weather systems.

"While the chain of dynamical feedbacks responsible for the observed changes in ENSO, past and present, remains unclear," the authors admit, "the prospect for larger ENSO extremes under continued greenhouse forcing greatly increases the societal and ecological vulnerabilities to climate change."

The study was published in Geophysical Research Letters.